Back in late June when the Senate signed off on President Trump’s legislation to alter federal spending priorities while keeping deficits stuck in the multi-trillion dollar (teradollar) range—The One Bloated Brobdingnian Bill (BBB)—the heroic Rand Paul was the only budget hawk to vote against it in opposition to deficit spending (in contrast to Democrats and a few centrist Republicans, who rejected the BBB’s shift in spending priorities away from Medicaid). Four other Senatorial budget hawks—Ron Johnson, Mike Lee, Rick Scott, and Cynthia Lummis—flipped their votes to “yes” after slightly greater Medicaid cuts were added to the bill, making it possible for J.D. Vance to cast a decisive tie-breaking vote in favor of the BBB.

Fast forward to November 10, and the Senate just barely mustered the 60 votes needed to pass a Continuing Resolution (CR) after more than a month of partisan bickering, prolonging current spending priorities but also allowing a previously scheduled cut in Obamacare subsidies to go into effect, which Democrats abhor. Senator Paul once again was the sole Republican holdout because of his opposition to Teradollar deficits, while Paul’s spendthrift Republican colleagues were joined by a handful of Democrats (thus ending the “shutdown Kabuki”) who were willing to give up the subsidies in order to resume full funding of the bureaucracy and of other transfer beneficiaries.

Both sides of the BBB/CR divide insist that Senator Paul is wrong to demand much larger spending cuts in order to reduce deficits immediately, claiming that their preferred (though diametrically opposed) tax policies would achieve significant deficit reductions in the long run by increasing tax revenues. Is there any truth to their beliefs about tax revenue offsets?

In the case of Republican spendthrifts, their argument is that keeping tax rates low and adding other targeted tax cuts will grow the economy faster, thus increasing revenues enough in future fiscal years to more than offset current spending increases. This “supply-side” narrative is derived from an economic theory associated with Arthur Laffer that Ronald Reagan popularized forty-five years ago. Laffer pointed out that there must be some optimal tax rate between 0 percent and 100 percent that maximizes the state’s revenue, so—all other things being equal—it is possible for a lower rate to generate higher revenue if it is closer to the optimum level than the higher rate.

While the Republican spendthrifts concede that there will still be deficits in the short run, they see these deficits as a temporary but necessary evil for funding a Pentagon arms build-up to wage costly wars abroad, and for funding Homeland Security to wage a costly war at home against an “invasion” by foreign vegetable pickers, hotel maids, food-cart vendors, janitors, etc., and their families (smeared as being the “worst of the worst” by Homeland Security). They pin their hopes on economic growth eventually solving the deficit problem.

In the case of Democrat spendthrifts, they oppose cuts to welfare state transfer benefits at the expense of the poor in order to keep income tax rates low for the benefit of the rich. Democrats also object to certain Republican spending increases, notably Trump’s war on immigrants. Democrats don’t dispute the existence of Laffer’s revenue-maximizing tax rate, but they believe that current tax rates are well below that level. They dismiss traditional Republican “supply-side” arguments as a “trickle-down” myth; they believe they can and should tax higher income earners more intensely in order to fund more benefits for the poor, if not institute “democratic socialism” in place of private earnings.

There are several intractable problems trying to resolve partisan disagreements about what the optimum Laffer rate is. First, Laffer’s curve describing the quantitative relationship between rates and revenues is constantly changing in unknown ways. Thus, we can’t use past data to rigorously model the shape of future curves. Second, the benefits of greater economic growth, and thus increased revenues, in the more distant future, even if realized with a given rate reduction, might be more than offset by the added costs of servicing the additional debts one accumulates in the nearer future. Third, not everything else is equal while tax rates are changed—there are many other causal factors that can affect economic growth. Higher near-term deficits are a particular concern because they might have to be financed at the expense of productive investments, thus offsetting any growth benefits derived from lower tax rates. For example, in OECD countries in recent decades, the share of GDP associated with government spending has been correlated negatively to real GDP growth rates.

Rather than take up the hopeless task of modeling future rate/revenue relationships, maybe America’s prior history of changes in tax rates for the highest and lowest income brackets and changes in GDP share of federal tax receipts and in real GDP growth rates would be more informative, keeping in mind the caveat that past correlations might not hold up in the future:

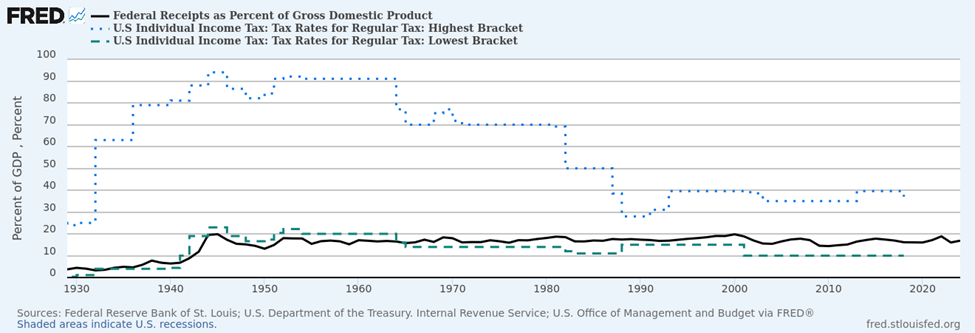

Figure 1—Federal income tax rates (percent) and federal receipts as percent of GDP

Sources: FRB St. Louis and IRS via FRED®

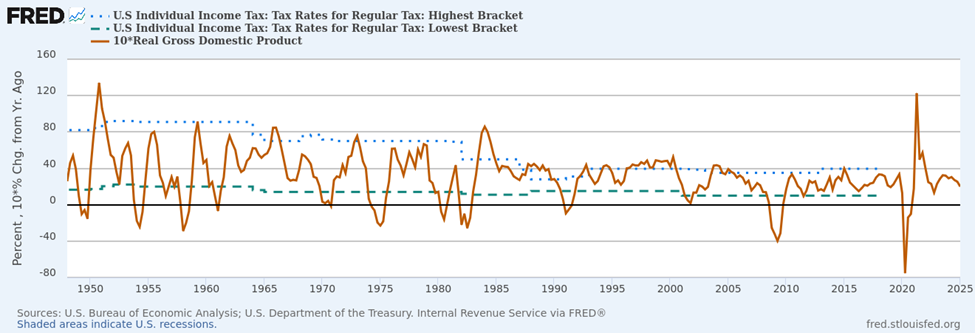

Figure 2—Federal income tax rates (percent) and annual real GDP growth rate (percent x10)

Sources: BEA and IRS via FRED®

The first thing we notice in these data is that the GDP share of federal tax receipts (figure 1) have been remarkably stable since the Second World War, averaging about 16 percent. Whatever small changes do occur seem entirely unrelated to the highest bracket’s tax rate. Likewise, there doesn’t seem to be any relationship between GDP growth rates and the tax rate of the highest bracket (figure 2). While such relationships might exist, their effects are far too small relative to other changes to be observable.

Both Republicans and Democrats are not telling the truth about the income taxes paid by the richest income earners in America—the rate for the highest bracket simply hasn’t mattered very much with respect to either revenues or growth. Herbert Hoover’s and Franklin Roosevelt’s huge increases in the highest bracket’s rate and cuts in that rate by John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, and George W. Bush did not have any discernible impact. Neither supply-side growth of GDP and revenues nor reduced soaking of the rich follows from lowering rates paid by the highest income earners. While the future might be different, there is nothing in past data to support either party’s claims of a significant relationship between changes of the tax rates imposed on high earners and subsequent federal revenues.

One correlation that is apparent in these graphs involves the tax rate paid by the lowest income bracket, and then only with respect to the share of GDP extorted as receipts (figure 1). This occurred when FDR started soaking the working poor more intensely just before World War II. If either party were serious about increasing revenues, maybe they should imitate FDR and try taxing the poor more intensely, though of course neither party dares do that.

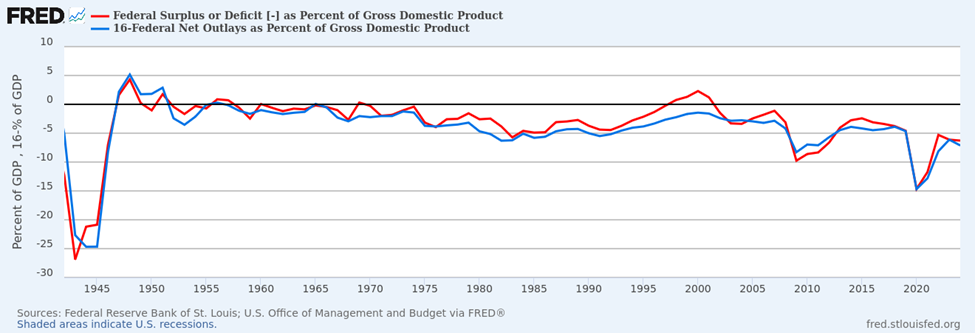

If the share of GDP taken as federal taxes remains stuck close to 16 percent of GDP, then the GDP share of deficits must closely track spending’s share. By subtracting federal outlays as a percentage of GDP from 16 percent, we can easily visualize just how closely changing spending levels has matched changing deficits as a percentage of GDP (figure 3):

Figure 3—Federal Deficits (percent) and 16 percent less Net Federal Outlays as percent of GDP

Sources: FRB St. Louis and OMB via FRED®

The facts are indisputable—since the Second World War, changes in deficits have always been closely correlated to changes in spending, not to changes in tax rates. Senator Paul, along with Thomas Massie—the corresponding sole budget hawk of the House of Representatives—are absolutely correct to focus on spending reductions as the only viable path towards reducing deficits.

Democrats need to learn that, while many among the very wealthy do unjustly profit from governmental rigging of market outcomes, steeply progressive income tax rates can neither unrig America’s corporatist economy nor fund its welfare state at present benefit levels. Playing Robin Hood with income taxes is neither practical nor just. The welfare state has simply grown too big to be sustainable; without cuts now, benefits will eventually be overwhelmed by hyperinflation or suffer forced reductions due to insolvencies of the Social Security and Medicare Trust Funds.

Likewise, Republicans need to learn that there is no magical economic growth fairy and get over their Libertarian Derangement Syndrome. These days no Republicans, apart from Senator Paul and Congressman Massie, dare to propose even the slightest cuts to Social Security, Medicare, the Pentagon, or Homeland Security, but that only makes increased deficits (made worse by compounding debt service costs) and accelerating dollar inflation inevitable. For all their tribalistic differences with Democrats over cultural issues, their spendthrift fiscal priorities put them in league with Democrats as a bipartisan fiscal cancer threatening to kill America’s economy with a metastasizing federal debt.