Net present value (NPV) is a popular decision-making criteria used by firms to make key, crucial choices about how to allocate resources across an economy. Net present value forecasts temporally discount future cash flows to their present value to check whether a project creates value. If a project has an NPV greater than zero, it creates value. On the other hand, if a project has an NPV less than zero, the project loses value. NPV forecasting isn’t perfect and there are often assumptions baked into any forecast but there is one particular type of error that occurs most often and has disastrous consequences.

A key component of a Net present value forecast is the Time Value of Money. The incorporation of the Time Value of Money in a NPV forecast is crucial to why it is considered a highly important tool for strategists and planners. Due to this, future cash flows from a project are temporally discounted from their nominal future value to their value at the present. This is because making a judgement requires that we deal with identical units rather than distinct units. Since the Time Value of Money shows that an amount of money is not worth the same at different times, NPV forecasting requires that all cash flows be converted to present values for the purposes of making a judgement.

To temporally discount future cashflows, there must be a discounting factor used. If the discounting factor were 0, then future cash flows would be equal to their nominal value in present terms. Due to the nature of time preference and human action, discounting rates are usually greater than 0. A discount rate of 5 percent annually would mean that a $105 in a year from now would equal a $100 in today’s money. Intuitively, we also know from this that a $100 now equals $105 in a year from now. Thus, the compounding rate being identical to the discounting rate yields identical values.

This is important as two parties with different value scales can trade intertemporally. If Person A values a $100 now greater than $105 in the future and Person B has inverse preferences then they can trade in a manner where they can maximize their values. Businesses do this when they budget for projects. If they believe that they can utilize capital to create value greater than market rate of interest then they will do so accordingly. They can do so by either taking loans, or using funds they may already have on this specific project rather than investing them.

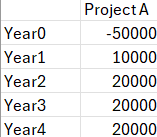

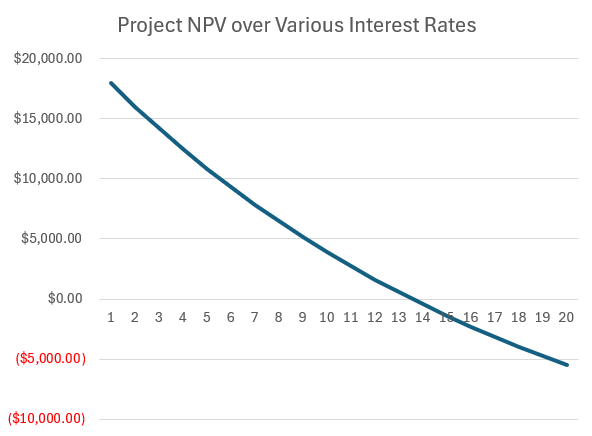

A crucial detail of note is that the market rate of interest is a huge factor in a NPV forecast. Projects that may have been profitable at a lower rate of interest may be extremely unprofitable at higher rates of interest. A crucial detail of note is that the market rate of interest is a huge factor in a NPV forecast. Projects that may have been profitable at a lower rate of interest may be extremely unprofitable at higher rates of interest. An example of a project with such cash flows is shown below:

As can be seen above, the project is only profitable while interest rates stay below 14 percent.

Interest rates are crucial to market calculation and altering them leads to the illusion that there is a greater supply of capital than actually exists. Due to this, firms bid up the prices of capital goods to use them in their new production processes. This cannot occur indefinitely as low interest rates force up prices as people bid up the prices of goods. Since central banks often lower rates when it is politically convenient, they do the opposite when circumstances change and price-inflation becomes a hot topic in public discourse.

When this occurs, NPV calculations change drastically as many projects that were supposedly profitable turn out to be lackluster and in need of liquidation. Unfortunately, it is a hard error to avoid as low interest rate loans can be alluring. In addition, it is also impossible to calculate the market rate of interest precisely because it arises from choice and action. When the choice and action in question are systematically altered, the results are altered too. The applicable lesson to be learned from such occurrences is that we must never lose sight of the assumptions within a model or within the process of making a decision. There are ways to check for the potential risk of such issues through sensitivity analysis. Conclusions drawn from erroneous premises will themselves be incorrect. A cluster of errors arises from artificially low interest rates and we come out worse off than without them.