The brief Mexican-American War (1846-1848) was one of the US’s five constitutional wars, that is, it is one of the only five ever declared by Congress. A brief history of the conflict can be reviewed in this 3-minute history video, as well as in Patrick Newman’s Cronyism. Of course, longer treatments of the war are also available.

Following the Republic of Texas’s declaration of independence—an act of secession from Mexico—on March 2, 1836, which was unrecognized by the Mexican government, Texas was later annexed into the United States on December 29, 1845. Of course, the Mexican government also did not recognize Texas’s annexation into the US. Many feared that annexation of Texas would be a provocation to war with Mexico. For example, on April 17, 1844, Henry Clay had warned,

Annexation and war with Mexico are identical. Now, for one, I certainly am not willing to involve this country in a foreign war for the object of acquiring Texas.... But I do not look upon this lightly. I regard all wars as great calamities, to be avoided, if possible, and honorable peace as the wisest and truest policy of this country....

Annexation would be to proclaim to the world an insatiable and unquenchable thirst for foreign conquest or acquisition of territory....

I consider the annexation of Texas, at this time, without the assent of Mexico, as a measure compromising the national character, involving us certainly in war with Mexico...

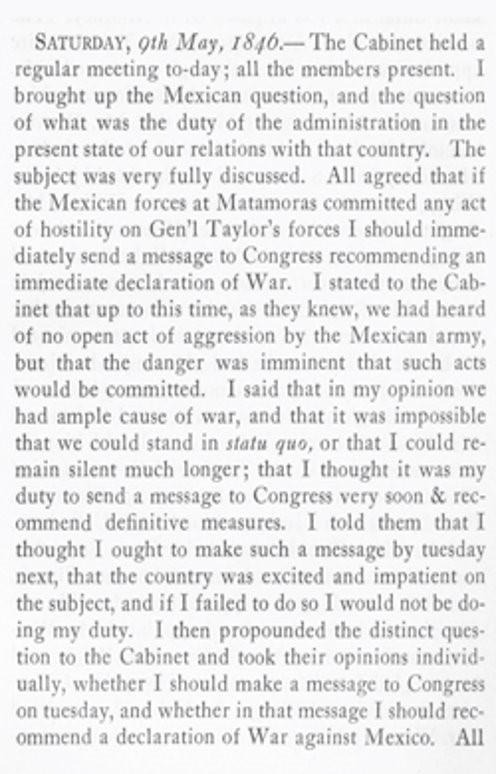

Fortunately, despite President James K. Polk’s efforts to provoke one, “Texas annexation brought no immediate war.” However, Polk still desired a war against Mexico and was determined to achieve it, but Mexico had to fire the first shot for the war to be at least perceived as legitimate national self-defense. Due to the disagreements following Texas’s unrecognized secession from Mexico and the US’s unrecognized annexation of Texas, from the perspective of the Mexican government, this left a disputed territory in Texas that would be fortuitous for Polk. President James K. Polk wrote in his diary (May 9, 1846):

I brought up the Mexican question,… All agreed that if the Mexican forces at Matamoras committed any act of hostility on Gen’l Taylor’s forces I should immediately send a message to Congress recommending an immediate declaration of War. I stated to the Cabinet that up to this time, as they knew, we had heard of no open act of aggression by the Mexican army, but that the danger was imminent that such acts would be committed. I said that in my opinion we had ample cause of war, and that it was impossible that we could stand in the status quo… (emphasis added)

Figure #1—James K. Polk’s Diary Entry (May 9, 1846)

Eventually, in March 1846, General Zachary Taylor’s forces crossed the Nueces River into the disputed territory, on orders from President Polk. Patrick Newman explains,

[Polk] ordered Taylor into the “disputed territory” near the Rio Grande, which was really Mexican land. In other words, Polk invaded Mexico and waited for the enemy to fire the first shot. In March 1846, the president informed Congress that he had stationed two-thirds of the army along the southwestern frontier.

Polk’s plan worked: Mexico attacked Taylor in April….

Polk undisputedly initiated a war of conquest and ruthlessly achieved his goal. The ramshackle Mexican government stood no chance of preventing the United States from capturing strategic ports and large swaths of territory. Furthermore, the conflict was undeniably what Whig Congressman Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia called an “Executive war,” and what others labelled “Mr. Polk’s War.”

Grant’s Memoirs and the War

While it is important to get the high-level political view of how and why the war took place, it can also be instructive to hear an eyewitness account from a young soldier who was there when the war was provoked—Ulysses S. Grant. Grant was only 24 years old when he was a soldier in the Mexican-American War. Toward the end of his life, twenty years after the end of the Civil War, Grant penned the Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant (1885). It is interesting to read Grant’s perspective on the Mexican-American War and war in general.

Regarding the president’s order for Zachary Taylor’s forces—which included Grant—to enter the disputed territory, he wrote,

For myself, I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day regard the war which resulted as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory.

He continued further with details about entering the disputed territory and why they were ordered to do so,

In taking military possession of Texas after annexation, the army of occupation, under General Taylor, was directed to occupy the disputed territory. The army did not stop at the Nueces and offer to negotiate for a settlement of the boundary question, but went beyond, apparently in order to force Mexico to initiate war. It is to the credit of the American nation, however, that after conquering Mexico, and while practically holding the country in our possession, so that we could have retained the whole of it, or made any terms we chose, we paid a round sum for the additional territory taken; more than it was worth, or was likely to be, to Mexico. To us it was an empire and of incalculable value; but it might have been obtained by other means. The Southern rebellion was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican war. Nations, like individuals, are punished for their transgressions. We got our punishment in the most sanguinary and expensive war of modern times. (emphasis added)

Following Taylor’s entrance into the disputed territory, past the Nueces and near the Rio Grande on Polk’s orders, actually provoking a fight, Polk boldly and untruly proclaimed on May 11, 1846, “Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood on American soil. She has proclaimed that hostilities have commenced, and that the two nations are now at war” (emphasis added). In contrast to the president’s statements about Mexico’s aggression against the United States, Grant wrote,

Mexico showing no willingness to come to the Nueces to drive the invaders from her soil, it became necessary for the “invaders” to approach to within a convenient distance to be struck.

In a later chapter, Grant continued,

The presence of United States troops on the edge of the disputed territory furthest from the Mexican settlements, was not sufficient to provoke hostilities. We were sent to provoke a fight, but it was essential that Mexico should commence it. It was very doubtful whether Congress would declare war; but if Mexico should attack our troops, the Executive could announce, “Whereas, war exists by the acts of, etc.,” and prosecute the contest with vigor. Once initiated there were but few public men who would have the courage to oppose it.... (emphasis added)

Grant made clear that the presence of US troops near the edge of the disputed territory was insufficient to induce the Mexican forces to attack, initiating a war. What was needed instead was for the US forces to invade, get attacked, then for Polk to argue that Mexico had invaded and attacked. This largely worked, but—to his credit—a young Abraham Lincoln, in the House of Representatives at the time, offered his Spot Resolution (December 22, 1847). This resolution sought important clarity: “...this House is desirous to obtain a full knowledge of all the facts which go to establish whether the particular spot of soil on which the blood of our citizens was so shed was or was not our own soil, at that time;...” In other words, did the “spot” in question actually reside within US territory or disputed Mexican territory?

Finally, Grant recognized something important involving the political and public momentum of wars. He knew that, “Once [a war was] initiated there were but few public men who would have the courage to oppose it.” Unfortunately, being correct about the facts isn’t enough; once political momentum for war has reached the public, it would require great courage and tenacity to oppose it. Grant recognized that, despite its enormous costs, people become committed to supporting a war,

Experience proves that the man who obstructs a war in which his nation is engaged, no matter whether right or wrong, occupies no enviable place in life or history. Better for him, individually, to advocate “war, pestilence, and famine,” than to act as obstructionist to a war already begun.

This is perhaps because the alternative to supporting a war comes with the high cost of social ostracism and the horrific realization that, despite the stated intent of the war, death and destruction has been supported for reasons other than the ones the public was told. In Grant’s estimation, one can gain more public popularity by positively arguing for destruction—war, pestilence, and famine—than against a war already started.