Europe became prosperous through a burst of innovation and capital accumulation during the eighteenth-century industrial revolution that allowed individual freedom to replace feudalistic rents and privileges. A new industrial revolution based on digitalization, advanced artificial intelligence (AI) and automation is in the making, but the reputed analyst Wolfgang Münchau claims that Europe is about to miss it. In his view, Europe has forgotten how to innovate, because it may still have the aptitude, but it has lost the right attitude to foster creative destruction. Münchau and other analysts put down this failure on European government’s inability to pick winners like China or capitalize on military investment like the US, in order to promote cutting-edge technologies and research. In our view this is wrong - Europe does not need more and better targeted government intervention, but considerably less.

Europe lags behind in productivity growth and innovation

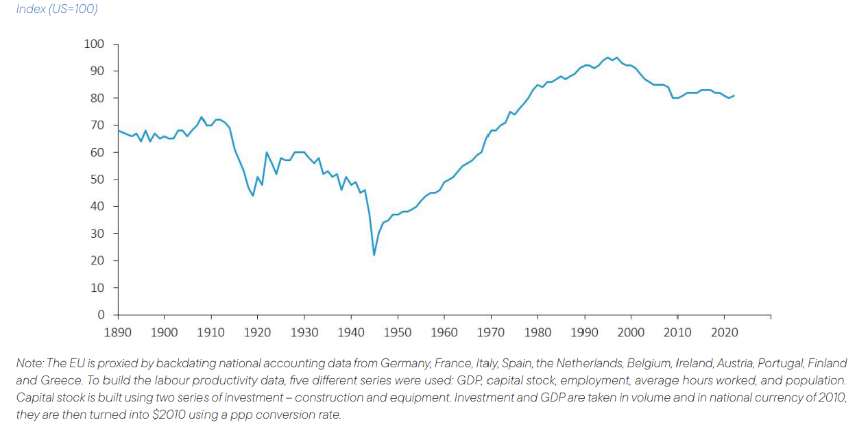

For almost four decades, Europe has been falling behind the US, and now China, in digital technology sectors, such as internet, semiconductors, ICT equipment and software, and AI. These sectors are recording the highest productivity growth rates and account for most of the widening productivity gap between the EU and the US (Graph 1).

Graph 1: EU vs US labor productivity 1890-2022

Source: The Draghi report: A competitiveness strategy for Europe (Part A)

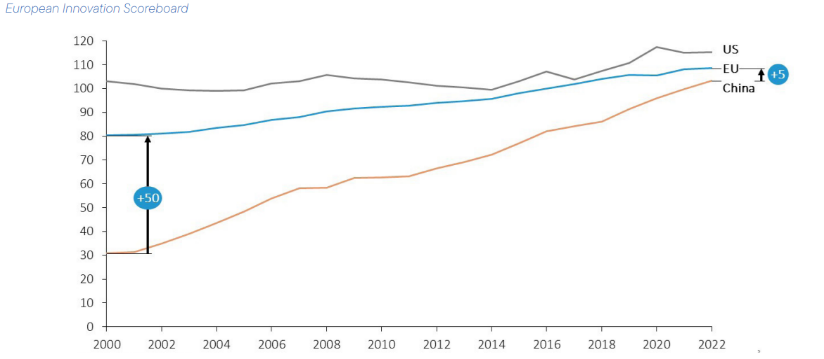

European decision makers could not just ignore the productivity growth problem and turned their attention to closing the innovation gap with the US. However, despite strong competition from China and the US, Europe still appears to retain a decent capacity to produce innovative ideas. According to Mario Draghi’s report on EU competitiveness, the EU produces almost one-fifth of the world’s scientific publications, lagging behind China, but ranking ahead of the US. It also has a strong position in patent applications with 17% of the world’s patent applications. EU’s public spending on R&D at 0.74% of GDP is slightly larger than 0.7% in the US, and 0.5% in both Japan and China. Overall, according to the European Innovation Scoreboard, the EU continues to trail the US closely in terms of scientific research (Graph 2), while China comes strongly from behind and outranked Germany in the latest Global Innovation Index 2025.

Graph 2: Innovation performance of EU, China and the US

Source: The Draghi report: A competitiveness strategy for Europe (Part B)

It seems that Europe’s main problem is not lack of scientific discoveries, but of providing the right conditions for businesses to develop them into marketable products. The links between higher education and businesses are weak. Only about one-third of the patented inventions by European universities or research institutions are commercialized. Successful commercialization in high-tech sectors is linked to innovation “clusters” of networks of universities, start-ups, large companies and venture capitalists (VCs) which are less developed in Europe.

The insufficient scaling up of tech start-ups is another key issue. Europe is creating a large number of start-ups, comparable to that in the US, but they often fail to grow. Many barriers, such as overregulation and bureaucracy, a heavy tax burden and insufficient access to finance force companies in Europe to stay small or relocate, mostly to the US. Only one in ten unicorns (i.e. start-ups with a valuation exceeding USD 1 billion) are active in Europe, relative to the US and China. According to Politico, nearly 30 percent of the bloc’s unicorns have transferred to the US since 2008. Young talent is also fleeing for the U.S. and Asia, while Europe’s economy is falling behind in modern industries.

Innovation does not work without capital accumulation

A disproportionate focus on innovation is not helpful, especially when Europe does not seem to lack innovative ideas. Ludwig von Mises explains how the scarcity of capital goods is the key factor impeding technological progress and the use of scientific knowledge. Throughout history, underdeveloped countries had relatively open access to the scientific methods used by advanced economies, but lacked the capital structure to implement them. The latter is the outcome of sustained market-oriented investment, where Europe seems to fail today.

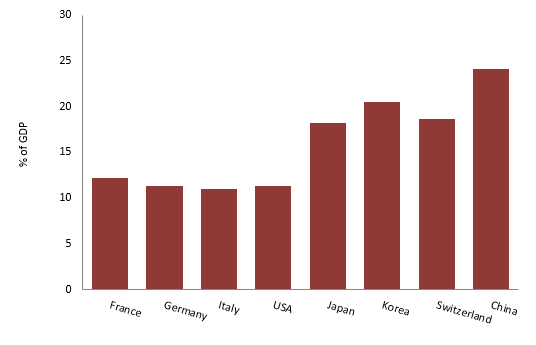

Only around 40% of European companies report that they invest in R&D, compared to 56% in the US. The overall R&D investment of the private sector in the EU was only 2.2% of GDP in 2022, compared to 3.5% of GDP in the US, 3.3% in Japan and 2.4% in China. In general, European companies invest somewhat less than the US, and considerably less than China, (Graph 3), which also explains the anemic capital accumulation and productivity growth.

Graph 3: Corporate sector investment

Source: OECD Data Explorer

Private investment in Europe is not low because of insufficient domestic savings, but because of heavy government intervention that renders the business environment unattractive. Domestic savings are actually plentiful in several old member states such as Denmark, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands and Sweden, but are mainly invested abroad. It results in very high current account surpluses (to the tune of 5 to 12% of GDP). As regards foreign investment, France, Germany and Italy have recorded a predominantly negative and volatile net foreign direct investment (FDI) balance, while US and China remain major destinations of FDI inflows in both absolute and relative terms.

Investors complain about the high regulatory and administrative burden, not least on account of severe labor market rigidities and the intrusive green legislation. Moreover, the tax burden is one of the heaviest in the world in order to finance an over-seized welfare state. According to the OECD, France, Italy, and Germany collect more than 40% of GDP in tax revenues, compared with less than 30% in the US and China. The perverse incentives of the generous welfare systems affect both companies and workers as it discourages education and hard work. Europe has an acute shortage of skilled employees in particular in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), undermining innovation. Despite the very large public spending on education, a steep decline in the level of basic skills and top performers took place in recent years, as evidenced by falling PISA scores. In terms of labor incentives, Germans and French work about 20% less hours per year than Americans and 30% less than Chinese.

Does Europe need more or less government intervention?

European decision makers focus on strategic solutions that favor more government intervention and policy centralization at EU level, such as higher public spending for innovation and education, faster decarbonization of the industry shielded by green tariffs, higher defense spending and strategic autonomy. They also target regulatory simplification, but remain conspicuously silent about reducing the tax burden and the welfare state, the real elephant in the room. European governments took a similar approach of protecting the welfare state, when recently confronted with fiscal and growth woes, either going for higher taxation in France, the UK, or Italy, or higher government spending in Germany.

Münchau also argues for more government intervention and believes Europe should emulate China in getting better at picking winners. But, the EU is no stranger to heavily subsidizing the industrial sector to the tune of 1.5% of GDP annually. It is also the originator of an artificial market for “climate change” compliant products, such as solar panels, wind mills, large capacity batteries, electric cars, etc. Normally, EU companies should be leaders in these markets, benefitting from the advantage of the first entrant. Yet, Chinese and other Asian producers took over “green” markets because they are cheaper and more competitive. If foreign companies investing in China in the early nineties were complaining about a “forced technology transfer,” now it is the EU requiring Chinese investors to transfer advanced technology know-how to their European peers.

In conclusion, it is not true that China has proven wrong the Western economic policy consensus that governments should never pick winners. China has only proven right the classic Western capitalist mentality that economic freedom stimulates hard work and capital accumulation, fostering prosperity. A relatively unencumbered capitalist system can be very productive at creating wealth so that, within limits, governments can waste some of it by subsidizing less efficient activities. But, if government intervention and redistribution reach a point where they stifle incentives to work, save and invest, privately created wealth may not be enough to cover government misadventures. Hence, the illusion that China is better than others at picking winners, and that better calibrated socialist policies could solve Europe’s problem of too much intervention in the economy.