Since submitting my last piece on this subject, the Irish government has produced their proposals for “revising” the system of rent control in Ireland. As expected, the government’s response involves further interventions that will—if all previous economic experience of rent control worldwide is repeated—result in further reduction in the supply of available rental properties, but still not enough intervention for the opposition parties.

Essentially the government has now extended Rent Pressure Zones (RPZs) to the entire country (in effect from June 20, 2025) and any tenancies in areas newly-designated as RPZ cannot be rent-reviewed for two years. After the first review, it reverts to annual reviews, but increases are still limited to the lesser of 2 percent and the annual change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

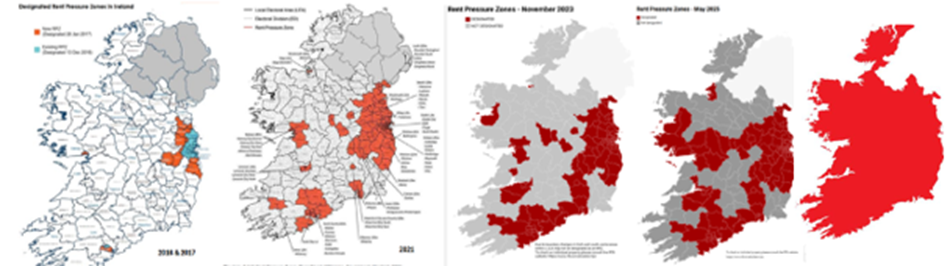

The gradual creep of socialist policy, with all the expected negative effects:

Further, the government has decided to stem the flight of property investors from the residential rental market (effective March 1, 2026) by outlawing any landlords with 4 or more rental properties (“large landlords”) from selling properties with vacant possession and permitting landlords with fewer properties (“small landlords”) to do so only every 6 years. Tenants must be left in situ otherwise.

Essentially, a small landlord who rents out a property must be prepared to leave it in the rental market for at least 6 years; and a small landlord with three such rentals, would be very strongly advised not to rent out another property because to do so would preclude the landlord ever selling any of those properties to anyone other than another landlord. The opposition, of course, thinks it’s a travesty even small landlords can service tenants with notice to vacate.

Remember landlords selling has been a steady source of supply for owner-occupier buyers over the last 10 years. The impact of the restrictions on landlords selling will be felt in that sector too! Also, keep in mind that Ireland still operates de facto price controls on residential property through the Central Bank of Ireland’s (CBI) mortgage lending rules, a matter I covered previously. The CBI have been loosening these over the last few years, but the effects of reducing the economic incentive to build new properties—compelling hopeful buyers to remain renters, with the consequent impact of pressuring rents up—persist.

We can address the constitutionality of these matters below, but in terms of the government’s stated goals of balancing tenant protections and encouraging investment (please don’t laugh), we can see where the “balance” has been struck. The only change to the law which could be said to benefit landlords is that they will have the right to reset rent where the rent is below the market rate at the end of each six-year tenancy, unless a “no-fault eviction” occurs. So when tenants decide to leave a property the landlord will increase the rent up to market rent for the next tenant. Even this one concession to landlords has outraged the opposition. Of course, given that all tenancies are generally subject to capped annual increases, that “market level” is likely to be anything but a level a free market would have produced.

As I pointed out previously, rent control was struck down as an unconstitutional attack on property rights twice in 1980’s Ireland. The RPZ regime slipped on to the statute books in 2016 (constitutionally speaking) in the hopes that time-limiting the operation of the regime and its apparently “intended” limited geographical scope would discourage an aggrieved landlord from challenging its constitutionality in the courts, which could be very expensive. Obviously it no longer has limited geographical scope. Further, the more draconian prohibitions on landlords selling properties are more likely to be considered as unconstitutional by a sane judiciary.

The bill enabling the RPZ regime to be established could have been referred by the president of Ireland to the Irish Supreme Court for a ruling on its constitutionality (“an Article 26 reference” under the Irish Constitution), prior to the president signing it into law. If such an Article 26 reference had been made and had the Supreme Court ruled it constitutional, the RPZ regime would be forever immune to constitutional challenge in Irish courts. Similarly, if the Supreme Court had ruled RPZs unconstitutional under such a hypothetical reference, it would be back to the drawing board for rent control. Article 26 has been used a mere 16 times since the establishment of the Irish State.

In my opinion, the reason RPZs were not referred under Article 26 to the Supreme Court in 2016 was that the then- and now-president of Ireland is an avowed socialist (much to Jacobin’s approval), and most definitely not a fan of Austrian or even Chicago School economists. Faced with a situation where he risked having a form of rent control being ruled as unconstitutional under an Article 26 reference (or it being copper fastened as constitutional), I believe that he chose to risk it being challenged in the courts once it had been passed into law, knowing only a plaintiff with deep pockets could or would raise such a challenge. The temptation to try to get it copper-fastened via the Article 26 reference must have been great, but even a socialist politician who once bemoaned his party “cutting back its socialist programme” recognized, in my opinion, that rent control might not survive such an Article 26 reference. Better to take half a loaf and hope it does not go moldy! Alas, price controls always make the subject of the price control go moldy.

The president’s term of office must end by November 11, 2025 as the Irish Constitution limits any president to a total of 14 years in office (2 terms of 7 years each). However, the candidates for election as his replacement are not yet known, and I can’t think of many I would trust. In any event, the recent changes to the rent control framework were rushed onto the statute books in a matter of days (once again without making an Article 26 reference).

The new changes referred to above may have, however, changed the calculus as regards the viability of a fresh constitutional challenge to the legislation. The blanket ban on large landlords serving tenants notice to vacate in advance of a proposed sale of a property may yet prove the Achilles’ heel of the rent controls. Again, rent control is one of those bad ideas which works nowhere (not even in Sweden), but which fools and/or knaves keep resurrecting in various locations and various times.