On October 9, zerohedge.com once again hosted a debate between libertarian financial author and podcaster Peter Schiff and pro-tariff author Spencer Morrison. As in their previous debate, Schiff emphasized the benefits of economic freedom on an international scale (including the voluntary hiring of immigrant labor as well as voluntary purchases of foreign-made goods) and the various harms that the American government’s taxes, regulations, welfare entitlements, and central bank money creation have inflicted on American industries.

While Morrison was sympathetic to some of Schiff’s points, it was evident that Morrison preferred to dismiss the free trade conclusions that follow from a valid logic of purposeful action by making false historical inductions from cherry-picked examples (confusing correlation with causation in the process) and by appealing to a methodological holism in fallaciously reifying nations as having an ontological existence and interests distinct from the individuals who compose the nation. Schiff did challenge some of the specifics of these errors, but Morrison’s underlying thesis that tariffs are necessary for reshoring jobs to America reflects his fundamental theoretical misunderstandings about the nature of international capital flows and production technologies that need correction.

Morrison’s justification for his thesis (cogently summarized in a recent article) is that countries like China have industrialized at the expense of American industries, specifically by Foreign Direct Investment (with the actual extent of FDI being concealed by capital flows being laundered through third countries), by the funding of Chinese companies via purchases of their exports (i.e., the trade deficit), and by Chinese breaches of restrictive technological privileges like patents covering American inventions.

Regarding the latter point, Morrison subscribes to an economic fallacy (an error that even Nobel Prize winners commit) that input factor productivity is a function of technology alone, without considering the crucial importance of the time required for transforming labor and natural resources inputs into outputs. The essential function of restraining present consumption (i.e., thrift) to finance investments is to make more time available for this transformation, making productivity gains possible by shifting inputs towards earlier stages of production. Savings, not technological knowledge, is always the key limiting factor on capital accumulation. As Ludwig von Mises noted in Human Action:

Let us look at the condition of a country suffering from scarcity of capital. Take, for instance, the state of affairs in Rumania about 1860. What was lacking was certainly not technological knowledge. There was no secrecy concerning the technological methods practiced by the advanced nations of the West. They were described in innumerable books and taught at many schools. The elite of Rumanian youth had received full information about them at the technological universities of Austria, Switzerland, and France. Hundreds of foreign experts were ready to apply their knowledge and skill in Rumania. What was wanting was the capital goods needed for a transformation of the backward Rumanian apparatus of production, transportation, and communication according to Western patterns.

What was true of Romania in the 1860s was also true of China in the 1980s. In the post-Mao era, the share of the Chinese economy devoted to capital formation eclipsed that of other industrialized powers, and its capital base has grown at a correspondingly faster rate in spite of some glaring inefficiencies in how capital is allocated in China.

It has been China’s greater devotion to savings and market-oriented reforms, not its sometimes dodgy acquisition of know-how, that explains its much faster growth. While it has been to America’s disadvantage that China could build up its human capital in American universities at the expense of American taxpayers and that American firms couldn’t infringe on monopolistic patent restrictions as readily as Chinese firms could, America’s self-inflicted folly of subsidizing foreign talent and of imposing domestic technology restrictions wouldn’t have benefitted Chinese production without Chinese savings.

Regarding trade deficits and capital flows, the very existence of a trade deficit means that net savings are flowing from China and other foreign countries into America. In claiming that American FDI in foreign countries is supposedly the root of all of the evil’s afflicting American industries, Morrison overlooks the fact that foreign lending to America has occurred on a vastly larger scale—contrary to protectionist myths, foreigners are in fact off-shoring their future productive potential to America. When foreigners sell more in America than they purchase from it, their excess dollar earnings are lent to Americans, giving Americans the benefit of foreign savings.

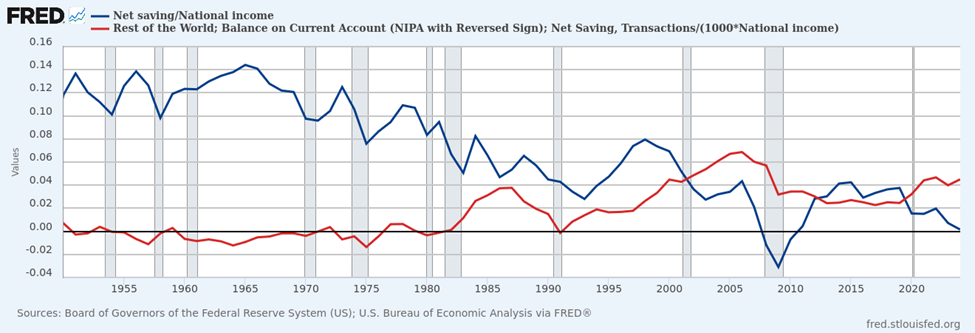

Figure 1 below gives a long-run perspective on domestic Net Savings and on net inflows of savings from foreign countries (the “Balance on the Current Account” of the rest of the world); both expressed as a fraction of America’s National income. While it may seem paradoxical that America has been deindustrializing even while foreigners have been showering Americans with their savings, this graph reveals the reason why this has occurred.

Figure 1: Net Savings (domestic) and net inflows of savings as a fraction of National Income, 1950-2025

Source: FRED

The blue line—representing the portion of America’s national income set aside to grow America’s industries—used to fluctuate between 10 percent and a little over 14 percent from 1950 through the early 1970s. Since then, the long-run trend has been dramatically downwards. The most recent figures show that Americans collectively don’t save any of their income. The red line, representing net in-flows of foreign savings (combining tiny outflows of Foreign Direct Investment together with large American borrowings from foreigners), hovered near 0 percent of America’s National Income through the early 1970s but then increased to a little over 4 percent today.

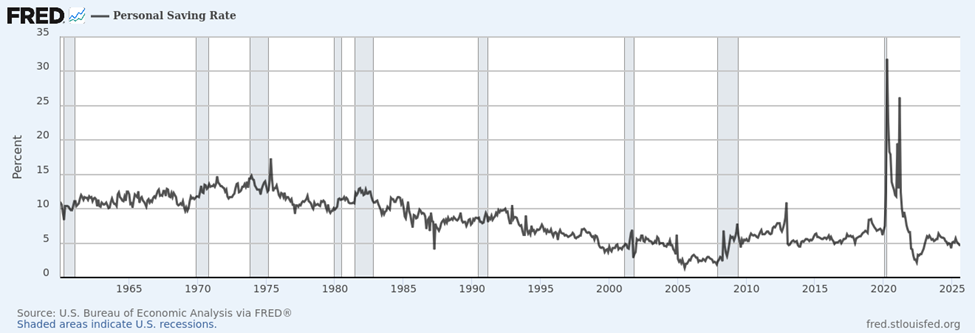

Thus, while America switched to borrowing savings from foreigners, its own domestic net savings have vanished. What changed in the early 1970s is that the dollar was cut off from its gold backing, enabling gigantic federal budget deficits to begin consuming ever larger portions of the available pool of private domestic net savings via Fed debt monetizations, even as the percentage of incomes being saved declined too. For example, the personal saving rate (shown in Figure 2 below) has plunged to less than half of the rates that were common up to the early 1970s, from the 10-15 percent range down to around 5 percent today (with the brief exception of the covid lockdown-related spike in savings), thus compounding the capital-consuming effects of massive federal deficits.

Figure 2: Personal Saving Rate, 1960-2025

Source: FRED

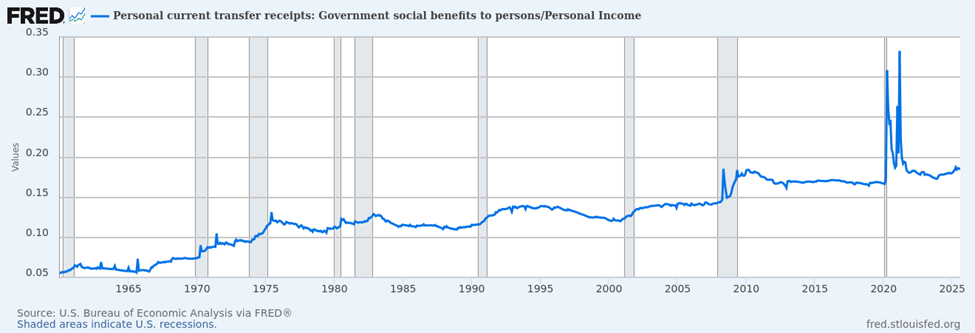

Another indicator of America’s grim savings predicament concerns the fraction of personal income derived from government social benefits—mostly Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and unemployment payments. Figure 3 shows these data.

Figure 3: Government social benefits as a fraction of Personal Income, 1960-2025

Source: FRED

The share of Personal Income derived from such transfer payments has soared from 5.5 percent in 1960 to over 18.5 percent today (with an even higher though brief spike during the covid lockdown). Not only has the Federal Reserve’s continual fiat money creation since 1971 driven real interest rates lower and made investing less rewarding, there is simply less reason to invest in the first place thanks to working-age individuals increasingly relying upon the federal government instead of their own investing to provide for their future economic security.

The growth of welfare statism is the major reason why American industries have been starved of investments and are no longer globally competitive. Enormous federal deficits both drain the available pool of domestic savings and make the available pool smaller by funding programs that persuade working-age individuals that they don’t need to save. One can only add that China, in contrast to America, got rid of its government-guaranteed “iron rice bowl” jobs and started encouraging ordinary Chinese to save and start capitalist enterprises of their own back when Deng Xiao Peng was in power in the 1980s.

Schiff pointed out that China, in spite of the enormous success it enjoyed as a consequence of its capitalist-oriented reforms, made the mistake of subsidizing America’s spendthrift ways through its purchases of American financial assets, particularly US Treasury securities. To the extent America can’t or won’t repay its debts, debt-financed trade deficits will ultimately prove to be more of a burden on the creditor (China) than on the debtor (America).

While Morrison correctly observed that Chinese industries have benefited a lot more from their relationships with American investors than is evident from China’s FDI statistics, the core problem is that Americans have benefited a lot less from the generosity of their foreign creditors in lending their export earnings to them. Americans squander their borrowed foreign savings on growing their welfare state, not on growing their industries. Large-scale trade deficits could in principle actually fuel massive reindustrialization and an increased real demand for American labor, but only via productive investments of the borrowed funds, which has not been the case with America’s post-1970 borrowing.

With a chronic dearth of domestic savings once again cropping up as the basic cause of America’s economic malaise, we must again confess (contrary to his uncomprehending critics) that Peter Schiff was right.