In recent years, the Fed has felt the need to step up efforts to defend its governing structure and its agenda. Thanks to the the success of the anti-Fed rhetoric of the Ron Paul campaigns of 2008 and 2012, combined with the financial crisis of 2008, the Fed has directly engaged the public more and more:

What followed [the Paul campaigns and the financial crisis] was several years of declining legitimacy for the Fed as a growing number of people began to understand what a central bank is, and what it does — and as the US went through the worst recession in decades. The public began to understand also that the Fed functions primarily out of the public eye — and without any meaningful accountability — while making decisions that can have an enormous effect on public policy and the economy.

By March 2011, the Fed capitulated and began to hold regular press conferences for the first time in its history. According to the Fed’s press release at the time: “The introduction of regular press briefings is intended to further enhance the clarity and timeliness of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy communication. The Federal Reserve will continue to review its communications practices in the interest of ensuring accountability and increasing public understanding.”

The Fed says that sort of thing because it has to, but it would obviously engage the public as little as possible, if it had the choice. After all, if it did want to engage the public, it could have introduced press conferences decades ago. It’s not as if the White house just started doing press conferences a few years ago, and now the Fed has decided to give this new-fangled thing a try.

Included among these efforts at self-rehabilitation has been efforts by the Fed to highlight its governance structure as somehow being representative of the public at large. We are told this is made possible through the Fed’s allegedly decentralized structure in which representatives from the Federal Reserve System’s member banks are able to have a say in policy formulation.

In practice, the Fed is dominated by interests out of Washington and New York — other member banks are largely window dressing. Nevertheless, there is no denying that there is at least a de jure committee structure, and this has helped the Fed deflect some criticism of the Fed as being dominated by a handful of powerful financial and political interests.

The latest addition to this public-relations drive by the Fed appears to be Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer’s talk in New York in which he defends the committee-based governance against demands that the Fed move in the direction of using rules-based monetary policy.

Fischer says:

The literature on monetary policy rules stretches back to at least Adam Smith and includes important contributions from David Ricardo, Knut Wicksell, and Milton Friedman.More recently, John Taylor has moved the research agenda forward with his eponymous rule, and a large number of academic papers have been written examining the effectiveness and robustness of policy rules. In contrast, as noted, study of the role of committees in making monetary policy has been fairly light, notwithstanding the insightful work of Alan Blinder and others.

Committees and rules may appear to be in opposition as approaches to policymaking. One might even argue that if a central bank ever converged on a single monetary rule, there would be no need for a monetary policy committee. In practice, the Fed operates through a committee structure and considers the recommendations of a variety of monetary rules as we make monetary policy decisions. Our decision is typically whether to raise or reduce the federal funds rate or to leave it unchanged. Committees can aggregate large amounts of diverse information--not just data, but also anecdotes and impressions that would be hard to quantify numerically. Good committees also offer a variety of perspectives and underlying economic models for interpreting the economy. In contrast, a policy rule, strictly defined, is numerical and constrained to a single perspective on the economy.

My own position is to be skeptical of the value of monetary-policy “rules” for reasons explained in these articles:

- The Problem With “Rules-Based” Monetary Policy by Tommy Behnke

- Could the ‘Taylor Rule’ Have Prevented the Housing Bubble? by Mateusz Machaj

If we read further in Fischer’s comments, however, we find that Fischer isn’t opposed to rules per se — he just thinks the FOMC (and presumably other Fed governance institutions) should be able to exercise a veto over proposed ”rules.” In other words, he thinks rules-based monetary policy should just be another model used by the FOMC to enact it’s preferred policy.

Indeed, the whole talk by Fischer amounts to a proclamation that “The Fed’s governance model is fine, and there’s no need for change.” The existing committee structure, Fischer tells us, works wonders for wise implementation of policy.

Fischer notes many advantages of the committee structure in terms of information gathering and “compromise.”

What he doesn’t note however, is that committees are also helpful in undermining opposition — and the Fed appears to be especially excellent at this.

When Fischer notes that “committees are less likely to take extreme positions — discussion, deliberation, and voting tends to drive policy outcomes toward compromise” what he’s really saying is that the Fed’s committee structure helps facilitate groupthink among the members.

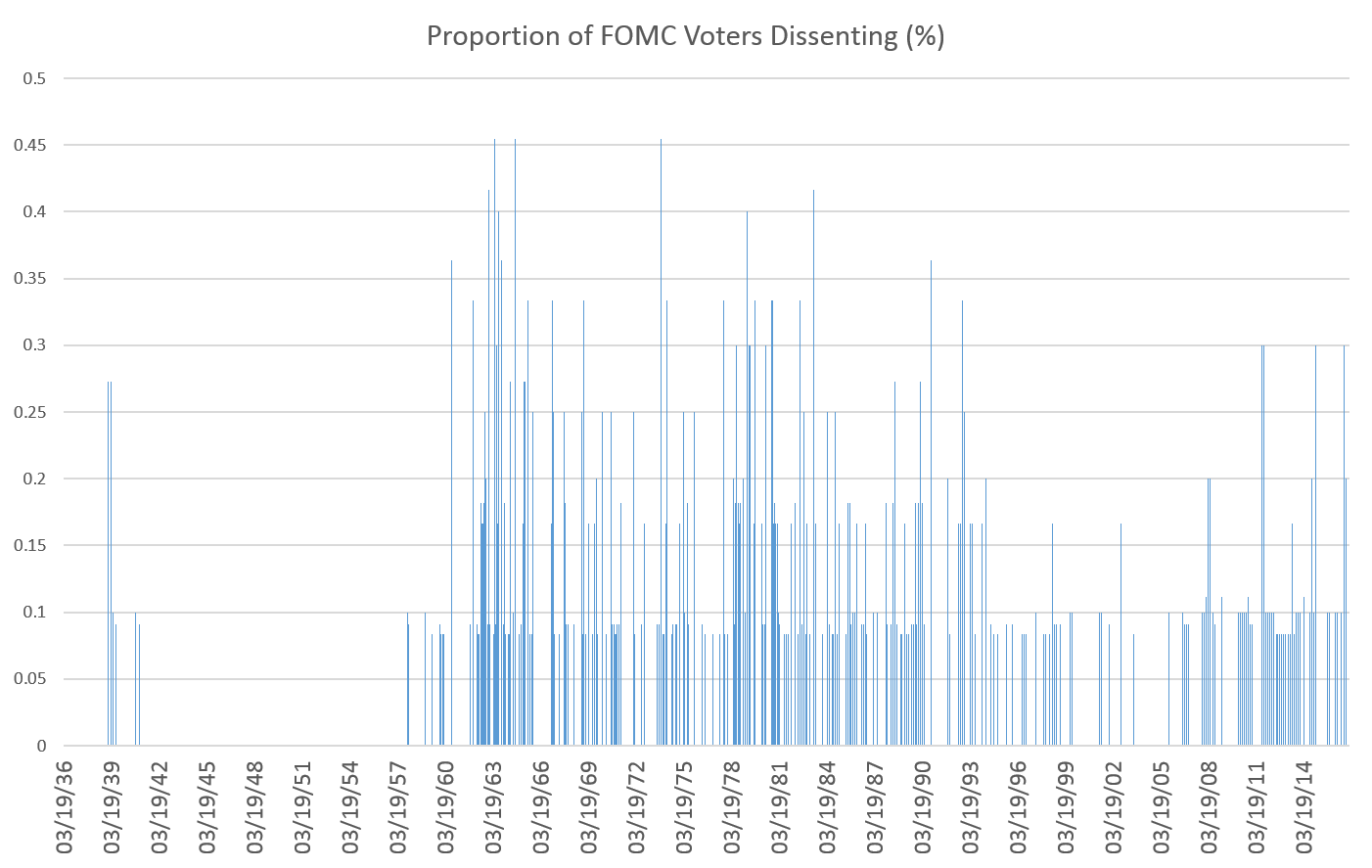

The voting records of the FOMC would suggest that the Fed’s governance structure encourages even less dissent than that found in many other political organizations — perhaps thanks to the fact that many of the FOMC’s members have few real obligations to anyone outside the Fed or the New York financial world.

If we look at the total number of dissenting votes at the FOMC, we find precious few dissents over the past 25 years, and — as we might expect — there are no cases of the proposed action being vetoed by the committee. Since 1992, there have only been four FOMC meetings at which even three people voted to dissent. For much of the 1990s under Greenspan, there was rarely more than a single dissenting vote.

It may indeed be the case that committees are helpful for exchanging information, but in the case of the Fed, the political advantages of the committee structure are much more likely to be found in that the committee helps give the impression of both representation and consensus to a political institution that actually functions with very little regard for interest groups and institutions not within its traditional confort zone.

Fischer’s speech may seem like a dry discussion of the merits of monetary-policy rules, but it’s really just another defense of the Fed’s status quo.