Both consumer and producer prices rose near multidecade highs last month. Price inflation rose to 8.6 percent while wholesale producer prices rose by more than 10 percent.

In both cases, a significant factor behind rising prices—but certainly not the only factor—was high energy prices. This has been reflected in prices related to transportation and shipping. Prices for air travel, for example, have seen some of the biggest price increases in recent months, while gasoline (naturally) has fueled sticker stock for households across the nation.

Perhaps most notable to the average consumer has been the increase in gas prices. In June, gasoline prices have risen on average to a new nominal high of over $5 per gallon.

Short of recession (or depression), relief will likely have to come in the form of increasing supply. The easy-money policies of the central bank have fueled spikes in demand for nearly all products, but this leads to a problem: rising demand has not come with rising production. In other words, the regime can easily increase the supply of money, by simply creating money out of thin air. But the regime can’t do the same with oil or gasoline. Unlike fiat money, oil and gasoline must actually be extracted and processed.

So, we end up with increasing supplies of dollars chasing oil and gas supplies that are increasing at a much slower pace. The result is rising price inflation.

Unfortunately, there does not appear to be much relief on the horizon. US bans on Russian oil have disrupted global oil markets and cut off the US consumer from ready imports. This certainly hasn’t helped bring crude oil prices down. But when it comes to gasoline prices, another sizable factor is the fact refineries are running below past capacity. Even when US markets have access to crude oil, gasoline production lags.

Much of this is being blamed on logistical problems stemming from covid lockdowns and the 2020 collapse in demand. As governments across the US forcibly closed businesses and issued stay-at-home orders, many refineries became unprofitable and closed. Shortly thereafter, an avalanche of newly created money whipsawed demand in the opposite direction, and refineries could not keep up. Prices spiked.

Ultimately, the situation only illustrated what more astute observers had pointed out: claims that policy makers can “pause” the economy, and that we need only wait for the “V-shaped recovery” for everything to bounce back to normal were very wrong.

Oil Prices and Gasoline Prices

During the worst days of the covid lockdowns, gasoline prices fell to around a dollar per gallon in many areas. The national average fell to near $2 per gallon in 2022 dollars.

But by late 2021, fueled by trillions in newly printed money, gasoline prices surged to ten-year highs. As of June 2022, gasoline prices have hit new highs of over $5 per gallon. Even in inflation-adjusted terms, gasoline will soon hit some of the highest prices seen in many decades.

Source: US Energy Information Administration.

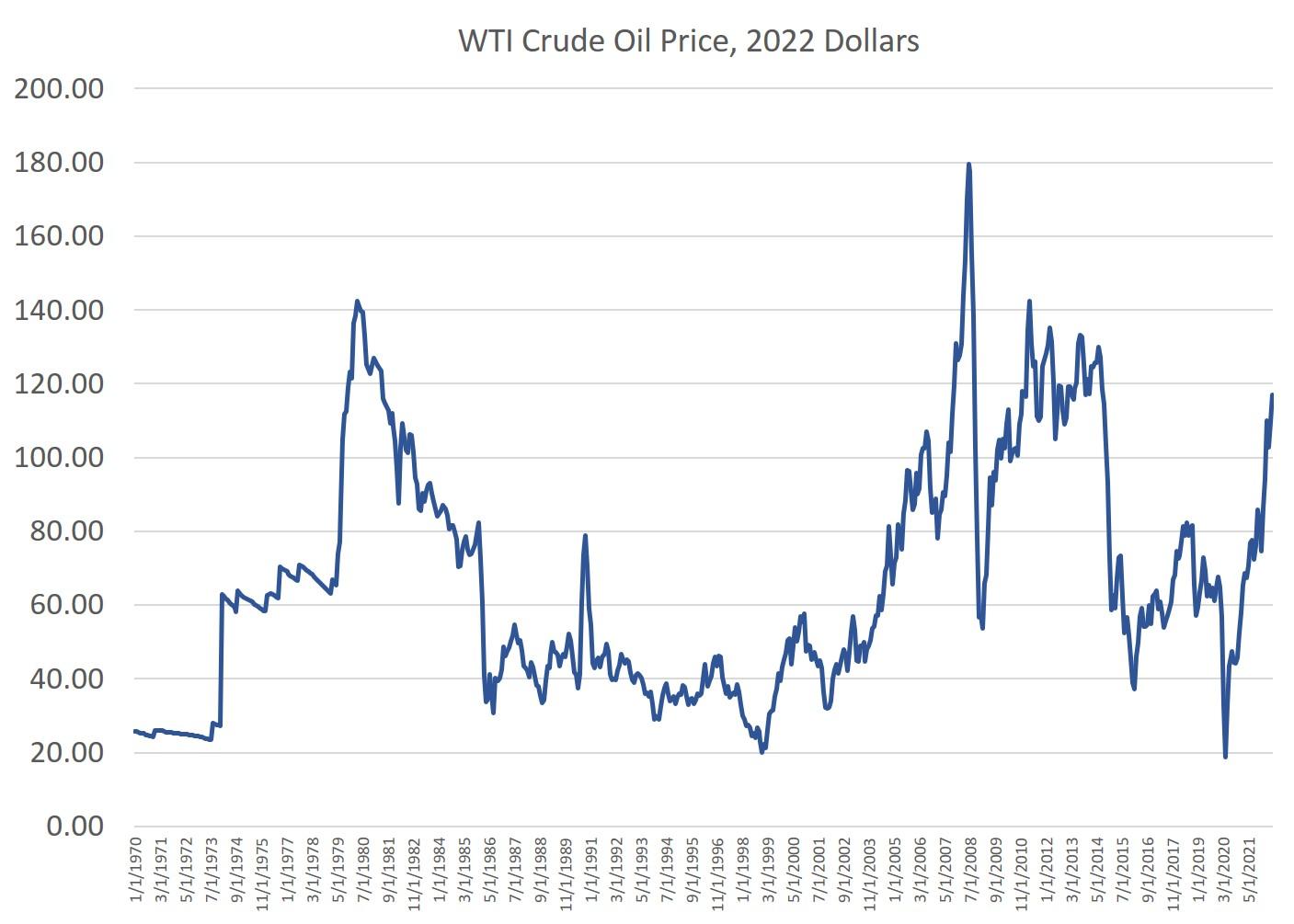

Notably, adjusting for inflation, gasoline prices have been outpacing crude oil prices. With crude oil prices rising to around $120 per barrel in recent weeks, inflation-adjusted prices have not yet risen to some of the highs we’ve seen since the 1970s. In the lead-up to the housing crash of 2008, for example, the oil price rose to nearly $180 per barrel (in 2022 dollars).

Source: FRED (U.S. Energy Information Administration, Crude Oil Prices: West Texas Intermediate (WTI) - Cushing, Oklahoma [DCOILWTICO], accessed June 15, 2022).

International Oil Markets Have Resisted US Saboteurs

The fact oil prices haven’t topped recent highs is due in large part to the resilience of international markets.

The Biden administration certainly did its best to drive oil prices through the roof, and thus to make life more difficult for the average American. In March of this year, the administration issued a decree banning Russian “crude oil and certain petroleum products” from the US. The administration boasted that American consumers would be cut off from seven hundred thousand barrels of Russian oil per day. Defenders of this policy lectured Americans on the need for “sacrifice”—by paying higher prices for oil—in order to make Washington’s Russophobes happy. This was part of a larger plan to pressure the regimes of the world into cutting Russia off from global markets.

This has certainly succeeded in driving crude prices above what they would have otherwise been. Fortunately, the plan has also partly failed. China and India have been buying up large amounts of Russian crude, ensuring that supply remains in the global market. This means global supplies are not strained as much as would have occurred had the Biden administration’s attempt at isolating Russia succeeded.

But while access to crude has not evaporated as the US regime intended, refinery capacity continues to lag. This has driven up gasoline prices to higher peaks than crude.

Nor is increasing capacity an easy affair. As Business Insider reported this week:

At the heart of the crisis is the fallout from the pandemic. As COVID rocked the world economy, energy consumption plunged, and many refineries shuttered operations.

Analysts at Wood Mackenzie, an energy consultancy, estimate that 3 million barrels a day of refinery capacity shut down in 2020 and 2021.

And once you shutter a refinery, it can be hard to get it running again.

“You introduce a lot of operational issues that come back to haunt you a few months later,” Claudio Galimberti, a senior analyst at energy consultancy Rystad, told Insider. “Running a refinery is very complicated.”

So much for that allegedly easy-to-reverse pause in the global economy we were told was no big deal. If running a single refinery is “very complicated,” imagine the complexity of an entire economy.

The usual anticapitalist response has been to place the blame on imagined “price gouging” or “greedflation.” President Joe Biden has reportedly sent an “angry letter” to oil company execs for not bringing down gas prices. Never mind, of course, that the administration has been committed to crippling fossil fuel production for the duration.