Unless members of Congress intervene to prevent it, the food stamp program—also known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)—will be suspended beginning November 1. If the federal partial “shutdown” ends before then, the program will likely send out the usual billions of dollars to the nation’s 41 million recipients on schedule.

Needless to say, lobbyists and activists who favor the food stamp program have been working furiously to make sure that the program is not interrupted.

Much of the narrative around food stamps has focused on the fact that millions of low-income households receive more than eight billion dollars in food stamps per month in the United States. The narrative usually works well given that total spending on food stamps has risen significantly in recent years with total inflation-adjusted spending up by nearly 100 percent since 2008, and up by six percent over the past twelve months.

[Read More: “41 Million (One in Eight) US Residents Are on Food Stamps“ by Ryan McMaken]

While the media narrative has focused on low-income recipients, it often ignores the role of corporate and industry lobbyists who work to increase food stamp spending and to ensure the program remains permanent. Farmers, “Big Ag,” grocery retailers, beverage companies, and other industry players are very active in lobbying members of Congress to ensure that food-stamp dollars keep flowing.

This should not surprise us when we consider that food stamps subsidize food and drive up demand for the sorts of products manufactured and sold by a variety of food-related industries.

Consequently, food stamp programs enjoy support from a well-funded alliance of industry lobbyists and “anti-poverty” pressure groups that ceaselessly push for ever larger amounts of tax-dollar funds to be spent on food stamps.

Food Stamps Are Subsidies and Push up Food Prices

To understand why private industry groups are such big fans of food stamps it’s important to recognize how SNAP spending is a wealth transfer from non-SNAP recipients to both SNAP users and to industry groups.

SNAP funds can be used only on food. So, when taxpayer dollars are converted into SNAP funds, this takes dollars that could have been spend on anything and channels those funds into food-only purchases. Moreover, empirical evidence shows that SNAP recipients do not treat SNAP funds as fungible with money in general, and the funds are thus part of a “separate mental account.” Consequently, SNAP spending constitutes “extra” spending above and beyond what would have been spent on food without the subsidy.1

This leads to rising prices in the food and food-services industry because “nutrition programs expand the size of the food and agricultural sector through demand-side effects and act to raise agricultural prices.”2

Other empirical studies have also confirmed that SNAP spending does indeed raise prices, and therefore constitutes a wealth transfer to SNAP recipients, food producers, and food retailers. Taxpayers and non-SNAP households, of course, are the ones left holding the bag. As Justin H. Leung and Hee Kwon Seo showed in a June 2022 empirical study of food stamps, the program does indeed benefit SNAP recipients the most, but “increased SNAP benefits also benefit producers at the expense of non-SNAP consumers.”

It is clear that by funneling wealth and spending power into a food-only benefits program, demand for food is artificially inflated, and with rising demand comes rising prices. This functions in a way similar to student loans, which have also led to relentless upward pressure in prices in that sector.

Food Stamps as Corporate Welfare

So, it’s easy to see why food-related industry groups would oppose any cuts to the SNAP program. The connection to private industry, however, is nothing new.

The food stamp program is now, and always has been, administered through the Department of Agriculture, and not through the usual home of welfare agencies, the Department of Health and Human Services. This is SNAP is as much a corporate subsidy program as it is a welfare program.

Programs similar to the modern food stamp program were founded during the Great Depression to induce low-income households to purchase “surplus commodities.” The early food stamp programs were justified on the grounds that they helped to stabilize prices by funneling additional dollars to farmers who might otherwise endure sizable decreases in prices for food stuffs that had been “overproduced.”3 As with many programs that were developed during the New Deal, a goal of food stamps was to increase prices.

The program was discontinued after the Second World War, but the idea was reintroduced by the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations. As with earlier iterations of the program, the new food stamp program—which continues today—was sold in part as a means of subsidizing farmers and other agriculture sectors. Moreover, the program was pushed as a component of the so-called war on poverty.

Ever since, the food stamp program has enjoyed support from special interests and pressure groups that advocate for more federal spending on both low-income households and food-related industries. In a 2019 article for The MIT Press Reader, Andrew Fisher writes:

Throughout the 1960s and until recent times, food stamps have enjoyed strong support from the agriculture industry. As retailers and processors displaced farmers in capturing an ever-greater share of the food dollar, their importance as stakeholders for the program grew. In the 2018 Farm Bill, banks, refrigeration equipment manufacturers and even the U.S. Chamber of Commerce join food retailers, beverage companies, and manufacturers as key stakeholders in the SNAP program. These players have evolved into much more important participants in the program than farm groups, as evidenced by the amount of money they spend on lobbying.

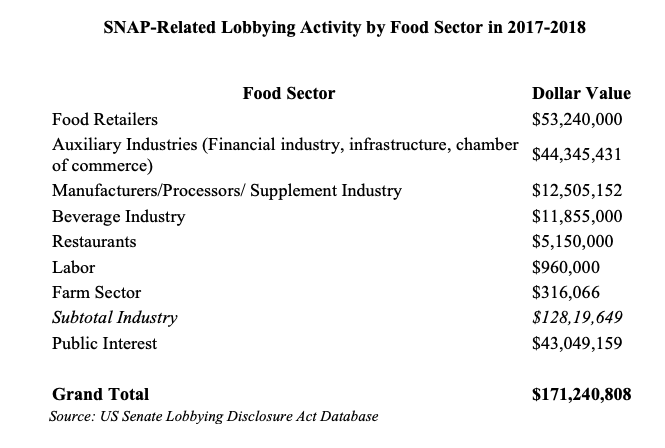

Fisher also notes that total lobbying activity by food-related industries exceeded $171 million in 2018:

Source: MIT Press.

Corporate lobbying to protect SNAP spending has been on display in recent years in reaction to efforts to exclude soft drinks and sugary snacks from SNAP programs. For example, in 2018, when the Trump administration tried to limit SNAP spending in this way, a coalition of private sector groups quickly opposed the measure. In an article for the journal Society, the authors describe how a coalition of the American Beverage Association (ABA), the Food Marketing Institute (FMI), and the National Grocers Association (NGA) all launched a lobbying campaign against any restrictions on SNAP spending.

To this end, industry groups have long allied themselves with the Food Research Action Center (FRAC) which lobbies for more SNAP spending as an “anti-poverty” interest group. Industry groups such as the ABA have become substantial funders of FRAC, and this has helped industry lobbyists gain greater access to Democrats while FRAC has used its ties to corporate lobbyists as a means of influencing Republicans. The pro-SNAP approach is thus bipartisan:

When seeking to influence Congress on SNAP, the beverage industry works through Democrats as well as Republicans, particularly those representing minority districts...

The beverage industry first began appearing on FRAC’s list of funders in 2013, and at FRAC’s 2014 annual benefit dinner a number of industry donors were honored, including Coke, Pepsi, and the ABA. FRAC’s 2017 annual benefit dinner in Washington, D.C., with 300 guests, acknowledged contributions from PepsiCo, the Coca-Cola Company, the American Beverage Association, and FMI.4

Not surprisingly, recent FRAC materials opposing any restrictions on SNAP spending tend to emphasize the cost to retailers. For example, an October 1, 2025 policy paper from FRAC states how SNAP restrictions would negatively impact members of the “National Grocers Association (NGA), FMI — The Food Industry Association, and the National Association of Convenience Stores (NACS).”

Although much of the lobbying is couched in terms of helping poor people, the overall argument made by both FRAC and industry lobbyists is that food retailers should not have to go through the inconvenience of distinguishing between SNAP-compliant foods and non-SNAP compliance foods.

FRAC and the food lobbyists don’t mention, of course, that merchants who participate in SNAP already have to do this. Grocery stores already carry a wide variety of products that are not SNAP compliant, including prepared foods, and non-food items such as flower arrangements and auto parts.

Clearly, the real purpose of the FRAC/Food Industry position is simply to maximize the number of goods that are eligible for SNAP and thus to increase spending on goods provided by food producers and retailers.

Small retailers—such as corner stores and bodegas—often whine the most about any limits on SNAP spending, stating that merchants cannot absorb the administrative costs of accepting SNAP dollars.

Rarely mentioned, of course, is that participation in SNAP is not mandatory. Small retailers—and indeed, large retailers too—could simply choose to not participate in SNAP programs and avoid all the hassle of excluding soft drinks and sugary snacks from real food. In truth, of course, these retailers want access to the artificially inflated spending levels that come with the food-stamp subsidy. This is why retailers so prominently advertise that they accept food stamps.

The motivations of the beverage industry are even more transparent. We already know that soft drinks are among the most popular purchases among SNAP recipients. Without the SNAP subsidy, spending on soft drinks would likely fall substantially, and with it, soft-drink prices.

Taxpayers then pay twice. They pay the taxes to subsidize food producers, and then the taxpayers also pay higher prices at the grocery store. Consequently, the SNAP program is a way for Pepsico and the Coca-Cola company—as well as countless other food-industry players—to legally rip off the American taxpayer.

- 1

Justine Hastings and Jesse M. Shapiro, “How Are SNAP Benefits Spent? Evidence from a Retail Panel,” The American Economic Review 18, No. 12 (December 2018): 3523.

- 2

Jeffrey J. Reimer and Senal Weerasooriya, “Macroeconomic Impacts of U.S. Farm and Nutrition Programs,” Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 14, No. 3 (September 2019): 625.

- 3

Marion Nestle, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): History, Politics, and Public Health Implications,” American Journal of Public Health 109, No. 12 (Dec 2019):1632-1633.

- 4

Robert Paarlberg, Dariush Mozaffarian, Renata Micha, Carolyn Chelius, “Keeping Soda in SNAP: Understanding the Other Iron Triangle,” Society , No. 4, (June 2018): 7-8