I always enjoy reading articles that talk about something that is doomed. Not because I have a negative view of the world, but because I always love to see why – the reasons behind the doom.

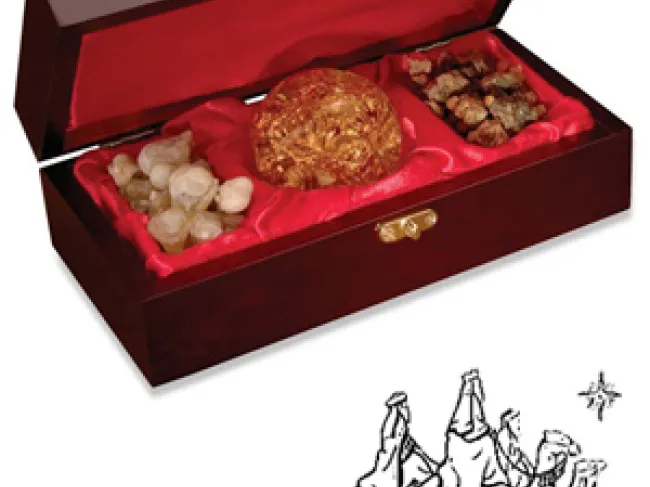

The Christmas time of year naturally brings stories related to the season. I recently stumbled across a news article stating that frankincense is “doomed”. Frankincense is perhaps most famously known from the Biblical account of the birth of Jesus Christ – Matthew 2:11 clearly states this. So, what is this substance, so important that is was mentioned in the Bible as being given to Jesus at his birth, and that is now “doomed”?

Frankincense is an aromatic resin produced from the bark of Boswellia spp. trees, which are native to Ethiopia, Somalia, and Yemen (and other places as well). The resin is harvested from the Boswellia trees by cutting the bark and collecting the resulting flow of resin, which is used as an oil, or in a hardened form. Many factors affect the quality of frankincense, such as the soil, climate, variety of Boswellia, time of year and frequency of harvest, and post-harvesting processing. All of these affect the terpene molecules present in frankincense, which in turn, affect the quality, and ultimately, the price of the final product.

Frankincense has various uses today, some of which are ancient in origin. The resin is burned in religious ceremonies at churches and mosques, is believed to have medicinal properties, and the essential oil of frankincense is used for various purposes, such as a component of perfumes.

A recent research report by Dutch and Ethiopian researchers has caused those who use frankincense to be filled with despair. The report paints a bleak picture of the future of Boswellia trees harvested for frankincense, indicating high tree mortality, and models that calculate a 90% reduction in tree populations in 50 years. Burning, grazing, and the actions of a beetle are cited as the reasons for the decline. In addition, trees that are heavily tapped for harvest are less likely than untapped trees to produce seeds that will germinate, although this is believed to be less of a problem than the other factors.

Even so, heavily-tapped trees produce seeds with only a 16% germination rate versus untapped trees, which produce seeds that germinate at least 80% of the time. What is going on here is an example of the concept of tragedy of the commons, as it is apparent that the Ethiopian government can forcibly relocate people (and therefore, the people do not have private-property rights on “their” land).

Ludwig von Mises summarized this when he wrote the following (from Human Action):

“If land is not owned by anybody, although legal formalism may call it public property, it is utilized without any regard to the disadvantages resulting. Those who are in a position to appropriate to themselves the returns – lumber and game of the forests, fish of the water areas, and mineral deposits of the subsoil – do not bother about the later effects of their mode of exploitation. For them the erosion of the soil, the depletion of the exhaustible resources and other impairments of the future utilization are external costs not entering into their calculation of input and output. They cut down the trees without any regard for fresh shoots or reforestation. In hunting and fishing they do not shrink from methods preventing the repopulation of the hunting and fishing grounds.”

Thus, in Ethiopia no one really owns the Boswellia trees (and not the land, either), and therefore, conservation for future use is not a goal – harvesting as much resin for frankincense is. They have no incentive to preserve Boswellia trees for the future. Also, the over-harvesting may leave the trees more susceptible to attack by beetles.

Whether intentional or not, the reports on the doom and gloom of frankincense paint a picture of state intervention and the resulting unintended consequences. The government effort to relocate people to the lowlands has proven disastrous – the highlanders’ cattle consume the saplings, and the people burn the land to make more grazing areas for the cattle herds. All of this state intervention, of course, is hard on the Boswellia tree populations and frankincense production.

One report attempts to blame a shift from large government-owned companies to small private groups on the demise of frankincense. The government operations provided for long contracts (up to 40 years), while the small, private companies will only give out short-term contracts for production (as short as 2 years). The article claims that this change in contract terms is responsible for depletion of Boswellia and frankincense.

But, this idea completely ignores the issues of private-property ownership and the resulting stewardship that comes along with it, as I stated above.

In addition, long-term guarantees from the government do not, in fact, promote sustainability. Indeed, they actually distort supply and demand mechanisms that are so important in the marketplace. Suppose that consumers demand less frankincense 10 years from now – producers might reduce harvest of resin from the Boswellia trees, and shift production to something else. With a 40-year contract from the government in place, producers would be less likely to pay attention to these natural market signals, and continue harvesting Boswellia resin to make frankincense, roughly at the same rate. Thirty years of overproduction of frankincense would occur in our scenario here, rather than reducing production in accordance with consumer demand, and allowing some of the Boswellia trees to regenerate. Thus, the government guarantees reduce the efficiency of resource use, and discourage people from making rational decisions.

Of course, supply and demand signals will ultimately decide what is produced, as prohibition and the current drug wars have clearly indicated. After all, the war on drugs seeks to prohibit voluntary trade and possession of plant products, with some horrifying consequences (as observed in the major ongoing drug war in Mexico).

So, is frankincense really “doomed”? Only if few people want it, and the government destroys property rights, while trying to save it with guarantees.