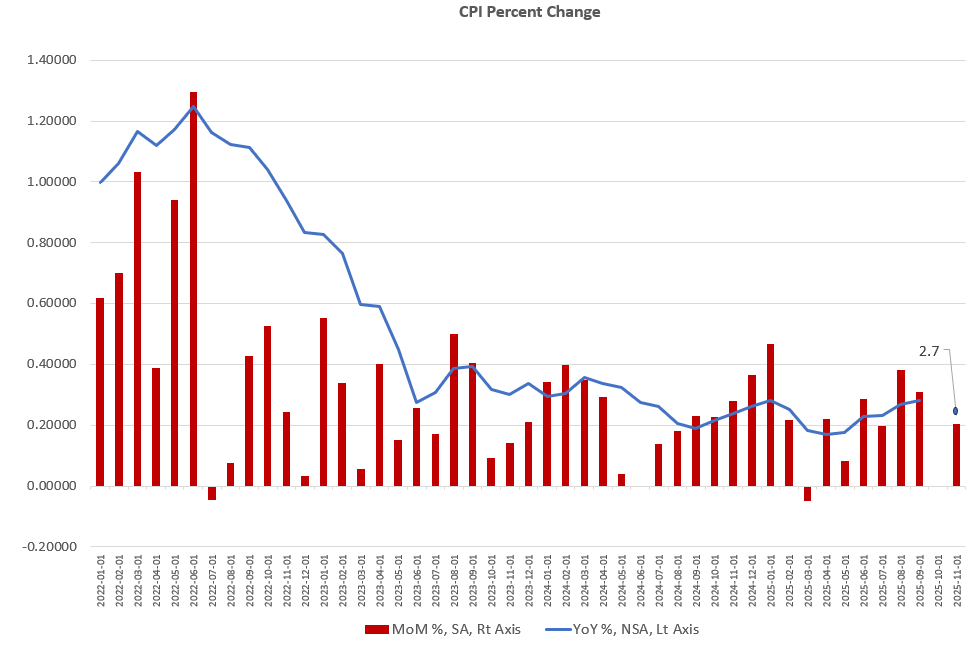

After a long delay, the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics today reported its price inflation report for the first time since the September report. According to the report, price inflation, as measured by the CPI slowed in November, both year over year, and from September to November. (Most October CPI data was not collected due to the federal shutdown.)

Measured year over year, CPI inflation in November was up by 2.7 percent, falling from September’s YoY increase of 3.0 percent. During the same period, the CPI rose by 0.20 percent from September to November. By comparison, the CPI rose by 0.31 percent from August to September.

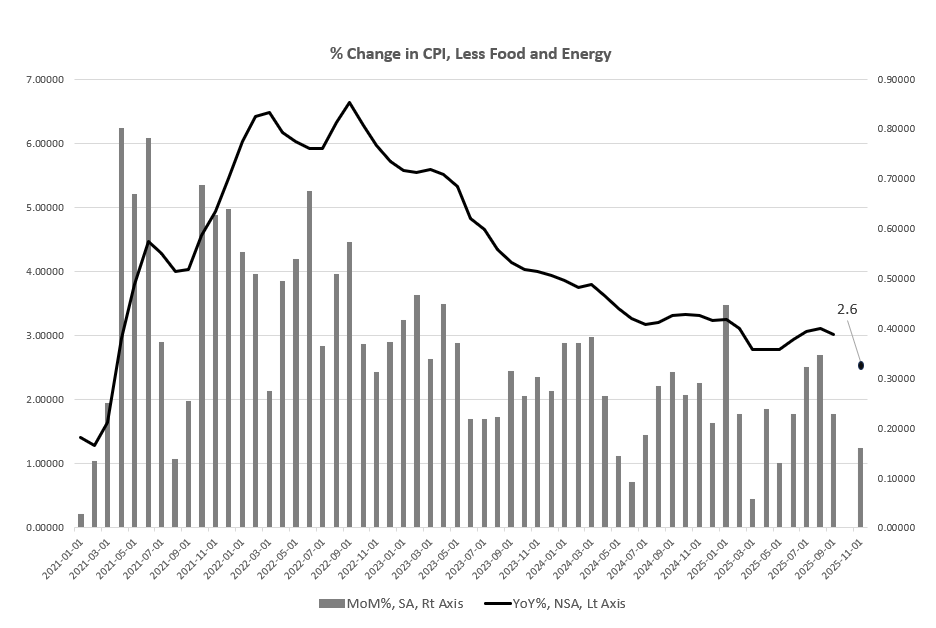

Removing volatile food and energy prices, the so-called core CPI showed similar changes. Year over year, the core CPI also slowed to 2.6 percent in November, falling from September’s YoY increase of 3.0 percent. Core CPI growth also slowed, growing by 0.16 percent from September to November, as compared to 0.23 percent growth from August to September.

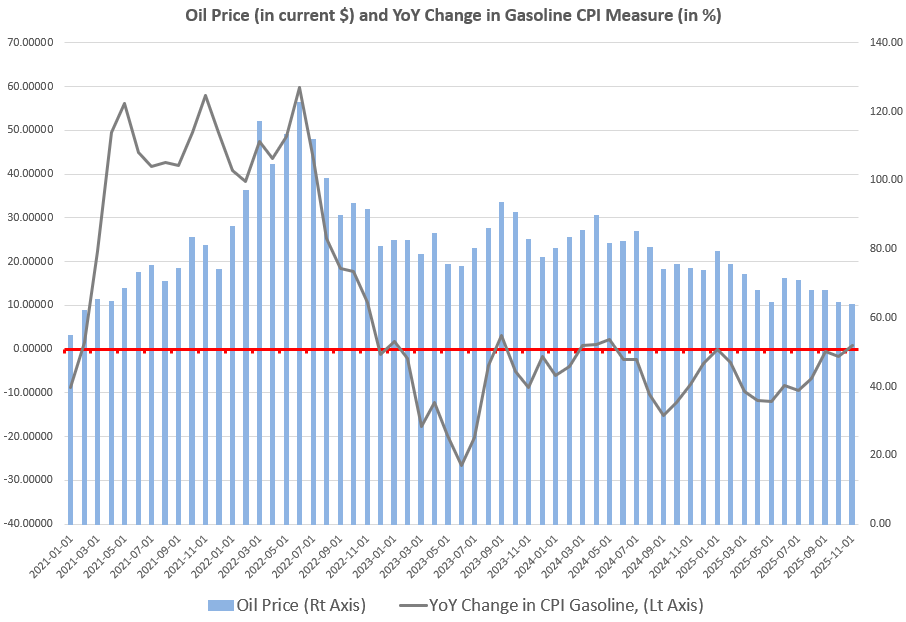

This downward movement in CPI growth—which remains positive and well above the Fed’s two-percent target—reflects, in part, falling oil prices which has helped to drive down gasoline prices as measured in the report. Year over year, the CPI index for gasoline has been down ten of the last 12 months, for example. And the oil price has fallen by more than twelve dollars per barrel over the past year.

Another factor has been a slowdown in rents in recent months. For example, the CPI for rent was up by 4.3 percent, year over year, during November of last year. This past November, rent growth had slowed to 2.95 percent. We can expect further downward pressure in rents and home prices—which will eventually also slow CPI growth—as BLS data catches up with current and ongoing downward movement in both rents and home prices.

For example, the National Association of Realtors showed a negative year-over-year change in median listing price for November. For the 12-month period ending in August, eight out of twelve months showed negative growth in prices for new houses sold.

This all reflects a general softening of demand as the global economy slows. As Jerome Powell noted at the most recent FOMC press conference, the labor market has slowed significantly in the United States, and new hires have virtually disappeared from the economy—the “job finding rate” has fallen to very low levels. Moreover, layoffs in October and November rose to levels not seen since 2009.

This helps explain, in part, why the Fed has continued to loosen monetary policy even as CPI inflation has failed to move back to the Fed’s two-percent target over the past year. Remember, for example, that it was back in September of last year when Powell claimed CPI inflation was moving swiftly back toward two percent. At the time, Powell was justifying the Fed’s cut to the target interest rate even as CPI inflation remained near 3 percent. (The cut was clearly politically motivated, but Powell had tom come up with some sort of excuse for the move.)

Powell and the Fed were clearly wrong, given that 14 months later, the CPI inflation rate is still closer to 3 percent than two percent. (The Fed’s preferred inflation measure, PCE, was still 2.8 percent in the most recent report, and the latest Cleveland Fed estimate still shows 2.61 percent.)

Yet, the Fed likely believes it can get away with lowering interest rates during a period of elevated inflation because the slackening economy will put downward pressure on demand, and therefore on prices. We’re already seeing it in oil prices and real estate prices. Economic weakness is also seen in rising delinquency rates, mounting bankruptcies, and similar measures.

This will mean falling prices in spite of continued monetary inflation. In other words, as we see price inflation growth flatten, it will be due to larger economic softening, and not to imagine Fed efforts to return to “price stability.”

Unfortunately, all this means ordinary people will have no chance of regaining any of the lost purchasing power—especially purchasing power lost due to supercharged price inflation that occurred during 2022 and 2023. The Fed will not allow prices to fall, no matter how much demand falls. That is, were the Fed to back off on its efforts to further fuel additional monetary inflation, price deflation would provide relief to consumers via falling prices. That won’t happen because the benefits of deflation will instead be nullified by continual monetary inflation from the Fed. As workers are forced to scrimp and cut back due to stagnation in employment and real wages, workers will still have to face rising prices. Powell, after all, admitted during December FOMC press conference that “conditions in the labor market appear to be gradually cooling, and inflation remains somewhat elevated.” This is also called stagflation. We can already guess what “solution” to the problem the Fed will choose. The answer is always “more monetary inflation.”