The World Bank recently announced that the world had reached a new milestone. Extreme poverty, the Bank explained, is likely to dip below 10 percent worldwide for the first time in 2015.

Extreme poverty, according to the WB, is a situation in which a person lives on an income of less than $1.90 per day. In other words, we’re talking about real, grinding poverty, and not a lifestyle at the poverty line in America where the poor have cell phones and air conditioning. In other words, this measure of poverty isn’t a relative measure, as is often used by the UN for measures such as its child poverty report.

According to the Bank:

The World Bank projects that global poverty will have fallen from 902 million people or 12.8 per cent of the global population in 2012 to 702 million people, or 9.6 per cent of the global population, this year.

Naturally, any downward trend in extreme poverty totals is a good thing. But the obvious question that must be asked next is why levels of extreme poverty have been going down. The World Bank claims that the improvements “were due to strong growth rates in developing countries in recent years, investments in people’s education, health, and social safety nets that helped keep people from falling back into poverty.”

That conclusion is fair enough as far as it goes. Certainly, transferring funds from one group of people to another group of people does tend to increase the latter’s group’s income. At least in the short term. Moreover, increased investment in education and health is a good thing. (It’s hard to tell if by “investment” it is meant real private investment, or simply government spending.)

However, regardless of how one feels about safety nets and government spending, the fact remains that before one can redistribute wealth, one must create wealth. A society that fails to increase worker productivity through savings and capital creation has no new surplus that can be spread around. We can redistribute wealth all we want, but if at least some workers and entrepreneurs aren’t creating more real wealth first, the end will result will simply be to redistribute poverty.

So to what can we attribute this ongoing decline in the worst kind of poverty?

To get a better sense of the causes of declines in poverty, let’s look at where in the world extreme poverty persists.

First of all, we must note that richest countries of the world have already eradicated extreme poverty. There are not people who live on $1.90 in the US, Canada, Australia, or Western Europe. These countries simply do not contain more than a negligible number of people who live in mud huts, walk miles a day to get clean water, and have no access to modern health care. Even in Eastern Europe, where Soviet-style socialism persisted into the 1990s, we rarely find a population with more than 1 percent of the population that endured extreme poverty levels.

So, we look to Latin America, Asia, and Africa to find the populations that continue to endure under conditions of extreme poverty.

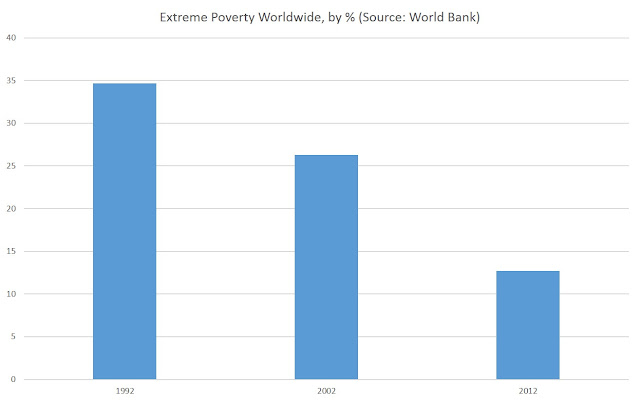

All data is from the World Bank and reflects data collected over the twenty years from 1992 to 2012, the last year that data is published. Worldwide during that period, extreme poverty fell from 34.7 percent to 12.7 percent.

Latin America is the least poor of the regions outside the wealthy west and Eastern Europe. The largest countries in Latin America have all been well below the worldwide rates for extreme poverty over the past twenty years:

\

\

In addition to seeing that Latin America has lower poverty in general than the world overall, we also can note that there has been substantial improvement in the twenty-year period. In Mexico during this period, extreme poverty dropped from 9.7 percent to 2.7 percent. Extreme poverty dropped even further in Brazil where the rate fell from 20.8 percent to 4.9 percent. In Columbia, the drop was smaller, but remained on the right track, with extreme poverty dropping from 8 percent to 6 percent.

Conditions are considerably worse in southern Asia and southeast Asia where extreme poverty rates exceeding 40 percent can be found. Nevertheless, in these cases we also find profound improvement over the 20 year period. In China, for example, extreme poverty fell from 57 percent to 11 percent. In Indonesia, the rate fell from 57 percent to 15 percent. Some of the least amount of progress was found in Bangladesh. But even , there, extreme poverty dropped by 20 percentage points from 63 percent to 43 percent.

The worst situation, however, was found in Africa where overall extreme poverty rates were higher, and the least amount of improvement was seen. Among the largest countries in Africa, we find that extreme poverty continues to plague large portions of the population, although significant improvement was experienced in South Africa and Ethiopia. In Ethiopia, from 1992 to 2012, extreme poverty dropped from 67 percent to 33 percent, and it fell from 32 percent to 17 percent in South Africa. So, why the disparities among regions and countries? If the world bank claims that poverty is reduced by safety nets and investments in health care and education, we must ask ourselves how a population obtains enough surplus to be able to afford safety nets and education and health care. The answer lies in greater participation in trade, more productive labor, and entrepreneurial activity. Also essential is a reliable legal system that protects private property. That is, the answer lies in greater freedom and security for market actors.

The developed world, for example, where extreme poverty has ceased to exist, is dominated by market economies. This includes allegedly “socialist” countries like Sweden and Denmark.

Indeed, if we’re looking at northern Europe in a broader global context, Europe is obviously characterized by at least partially-free markets. Having a market economy is seen as a good thing as was recently shown when the Prime Minister of Denmark complained that Bernie Sanders ought to quit calling Denmark a socialist country. Denmark, according to the PM, is ”far from a socialist planned economy. Denmark is a market economy.”

In the big scheme of things, he’s right. Denmark bears little resemblance to the “planned” economies that were popular in much of the world in the mid-20th Century. And it is Denmark’s relative openness to trade and entrepreneurship that makes it rich.

Yes, it is poorer than it would otherwise be thanks to a multitude of government regulations and redistributive policies, but if we look at the country in global context, we have little trouble understanding why Denmark is so much richer than, say, India, which until the 1990s, labored under an extreme regulatory burden. India is still trying to catch up to Denmark, and won’t do it for decades, if not centuries.

Latin America, for its part, has cut its poverty rates so greatly thanks to its embrace of market economies as well. Chile is an enormous success story, and, if it remains on its relatively pro-market path, is likely to become one of the richest countries in the world over the next generation. While poorer than Chile, Mexico is a success story as well, and the emergence of a middle class there over the past twenty years is a sign of an ongoing commitment in the country to slowly moving away from centuries of government dominance in the economy. People who still refer to Latin America as the “third world” are hopelessly behind the times.

And, of course, Mexico, Chile, — and other Latin American states where extreme poverty is disappearing — have simply been participating in the global economy longer than much of the world.

For all their starts and stops, and booms and busts, Latin America has been at least somewhat geared toward market economics since the 19th century. The same cannot be said for Asia and Africa, however. Long dominated by Marxist economics on the one hand, and exploitive colonial mercantilism on the other, African countries have done little, even in the last twenty years to create favorable conditions for thriving economies. Plagued by war, corrupt legal systems, and ideologies that have contempt for private property — such as Islamism and Marxism — poverty continues to dominate the African landscape today.