Since the introduction in 1912 of Ludwig von Mises’s Austrian business cycle theory (ABCT) in his book The Theory of Money and Credit, it has been subject to relentless criticism. According to the ABCT, the artificial lowering of interest rates by the central bank via inflationary credit expansion leads to a misallocation of resources on account of the fact that businesses undertake various capital projects that, prior to the lowering of interest rates, weren’t considered profitable. This misallocation of resources is commonly described as an economic boom. The process, however, is brought to a halt once businessmen discover that the lowering of interest rates is not in accordance with consumers’ time preferences.

As a rule, businessmen discover their error once the central bank—instrumental in the artificial lowering of interest rates via artificial credit expansion—reverses. This, in turn, halts the expansion and an economic bust ensues. It follows, then, that the artificial lowering of interest rates by the central bank sets a trap for businessmen by luring them into unsustainable business activities that are revealed once the central bank tightens its interest rate stance.

Critics of the ABCT maintain that there is no justification for the view that businessmen should fall prey again and again to the central bank’s activities. Businessmen are likely to learn from experience, the critics argue, and not repeatedly fall into the trap produced by the central bank lowering of interest rates. Consequently, correct expectations will undo or neutralize the whole process of the boom-bust cycle that is set in motion by the lowering of interest rates. Hence, it is held that the ABCT is not a serious contender in the explanation of modern business cycle phenomena. According to Gordon Tullock,

One would think that business people might be misled in the first couple of runs of the Rothbard cycle and not anticipate that the low interest rate will later be raised. That they would continue to be unable to figure this out, however, seems unlikely. Normally, Rothbard and other Austrians argue that entrepreneurs are well informed and make correct judgments. At the very least, one would assume that a well-informed businessperson interested in important matters concerned with the business would read Mises and Rothbard and, hence, anticipate the government action.

(Also see Ludwig M. Lachmann, “The Role of Expectations in Economics as a Social Science,” Economica, February 1943. Also, see Salerno’s comment on Tullock and Tullock’s reply.)

Do Expectations Matter?

According to the critics then, if one allows for the possibility of expectations, this could prevent boom-bust cycles. This way of thinking would be valid if the issue would have been only the lowering and lifting of interest rates. There is no doubt that businessmen would have quickly learned to disregard the ups and downs in interest rates and would have utilized some long-term average of interest rates in their investment decision process.

On the other hand, ABCT is not just about variations in interest rates, but about variations in the monetary policy of the central bank, which amounts also to changes in the money supply growth rate. The inflationary increase in the money supply through the expansionary monetary policy of the central bank sets the platform for the exchanges of nothing for something. This sets in motion the diversion of resources from wealth-generators to the holders of the newly-generated money and credit. Observe that resources, instead of being employed in wealth-generating activities, are now employed in non-wealth-generating activities. Consequently, economic growth comes under pressure. In response to this, commercial banks are likely to curtail the expansion of credit. This, in turn, puts downward pressure on the growth rate of the money supply.

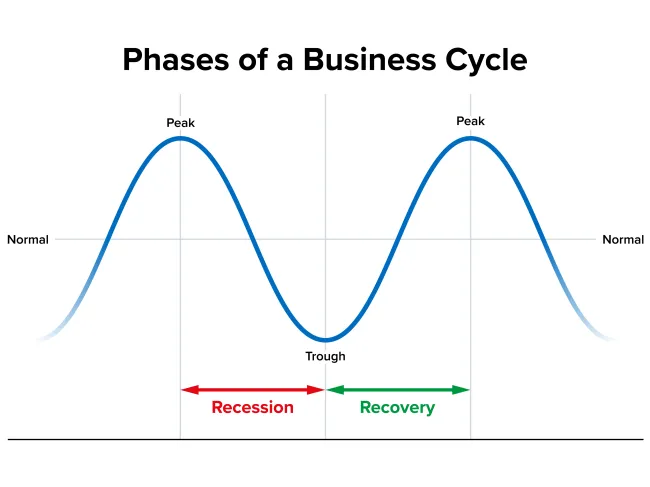

Now, increases in the growth rate of the money supply gives rise to various non-wealth-generating activities and distort the structure of production. This is an economic boom. The decline in the growth rate of money supply weakens these activities. This is an economic bust. Hence, the boom-bust cycle.

The bust is not simply due to rising interest rates, but rather on account of the prior expansionary monetary policy. This means that the expansionary monetary policy of the central bank plants the seeds for an economic bust.

Now, even if businessmen were to anticipate the timing of the central bank monetary policy, this anticipation could not prevent the boom-bust cycle once the central bank has embarked on an expansionary monetary policy. Hence, once the central bank has embarked on an expansionary monetary policy, it is not possible to undo the boom-bust cycle because of businessmens’ anticipation of the central bank’s conduct. We can conclude that the businessmens’ expectations of central bank interest rates policies cannot prevent boom-bust cycles once the central bank has embarked on an expansionary monetary policy.

Also, even if businessmen have correctly anticipated the interest rate stance of the central bank and the subsequent changes in the growth rate of money supply, because of the variable time lag from money changes to its effect on economic activity, it will be almost impossible to establish the timing of the boom-bust cycle. On account of the time lag, prior changes in the money supply could continue to dominate the economic scene for an extended period. (Given that the time lag is variable, it is not possible to ascertain when a given change in the money supply growth rate will start to dominate the economic scene and when the effect of past changes in money supply will vanish).

Now, the job of businessmen, metaphorically speaking, is to stay on guard as far as consumers’ demands are concerned. So, whenever they observe growing demand, they react to this. For instance, if a builder refuses to act on a growing demand for houses because he believes that this is because of expansionary monetary policy and cannot be sustainable, then he will be out of business very quickly. To be in the building business means that he must be in tune with the demand for housing. Likewise, any other businessman in a given field will have to respond to changes in the demand in the area of his involvement if he wants to stay in this business.

Hence, a businessman has only two options—either to be in a particular business or not be there at all. Once he has decided to be in a given business, this means that the businessman is likely to respond to changes in the demand for goods and services in this particular business, irrespective of the underlying causes behind the changes in the demand. Failing to do so would put him out of business.

Conclusion

According to the critics of the Austrian business cycle theory (ABCT), anticipation by individuals of central bank monetary policies could prevent the boom-bust cycles, thereby making the ABCT invalid. We suggest that it is not possible to undo the boom-bust cycles notwithstanding individuals’ expectations once the central bank has adopted an easy monetary stance. The business cycle is a consequence of a real act of damage that, once set in motion, cannot be undone.