Libertarians talk a lot about the need to weaken—and even to abolish—the state. And rightly so. But a necessary part of opposing the state is building up other institutions that can challenge state power and offer alternatives to the state. That is, if we are to meaningfully undermine the state, it is necessary to encourage, grow, and sustain robust non-state institutions such as churches, families, and private markets. These are the institutions of what the old classical liberals called “civil society.”

Perhaps the most important of these institutions is the family. Among all human institutions, the family is, by far, the most “natural” in the sense that it has existed always and everywhere that humans exist. It is fundamental to the human experience in a way that the state never has been, and never can be.

The state, after all, is neither natural nor necessary, and has only existed in certain times and places. Nonetheless, when and where the state does exist it seeks to weaken and replace all other institutions. During the rise of the modern state in Europe, this has certainly been true as state agents have worked to take control of churches, supplant the nobility, and abolish the independence of municipal and regional polities.

Similarly, the state has sought to supersede the family. This it has done with a myriad of strategies including government schooling, the military draft, the welfare state, and inheritance taxes. Families have always been a threat to state power because families often attract the loyalty of individuals away from state institutions, and families can be critical in offering individuals economic and social stability.

In this endeavor to destroy the family, the state has been increasingly successful in recent centuries. Although the family still exists today, it does so in a greatly weakened state.

This has implications for all other institutions of civil society, as well. Research in recent decades has shown that married couples with children—i.e., intact families—are foundational to the sustainability of religious institutions, charitable organizations, volunteerism, neighborhood stability, and for local social institutions that build the fabric of stable communities. The decline of the family—which has been precipitous since the 1960s—has been a key factor in the decline of these other institutions as well.

In other words, family demographics have been a critical factor. As marriage rates and birth rates have declined, civil society has declined and state power has grown.

Indeed, from the perspective of the state, the ideal demographic makeup of society is likely one composed of single parents raising a small number of children in irreligious households. These types of weakened families are shown to be less engaged civically, more fragile, more mobile, less economically prosperous, and less engaged with religious institutions. All of this this helps ensure weak social bonds coupled with perennial dependence on the state.

Families Are More Active in Building Civil Society

Civil society has always been much more than the market institutions that exist within it. A functioning society is comprised of countless informal social networks among institutions, within neighborhoods, and within families themselves. Without this, there can be no “high-trust” societies and the result is higher levels of social isolation, crime, and poverty. Moreover, the social skills and loyalties central to the preservation of civil society must also be passed down to future participants.

For many years, some social scientists pushed the theory that members of stable families are less social and less inclined toward civic engagement. Evidence to the contrary continues to pile up, however, and popular books like Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone shows what has long been obvious to many: that the abandonment of earlier marriage and childrearing patterns has led to more social isolation.

Married parents are often the key group that is essential to maintaining these networks and institutions. For example, in a 2010 study, Richard Caputo found that

Families play an important part in the transmission of civic-mindedness: horizontally through interactions with other adults in community and church-related activities which reinforce and help spread civic culture and vertically as parents socialize their children. ...

Married persons were found to volunteer more than unmarried, due primarily to increased opportunities to do so arising from their children’s school among other venues ... the modal volunteer was found to be the married parent with children, especially of school-age, living in the household.

“Civic engagement” can mean a lot of things, but married persons were found to be especially active in “non-activist” civic engagement such as community fundraisers, supporting local businesses, and donating time to non-political organizations. Caputo notes “more than one-fourth of married persons (28.5%) were non-activist volunteers, nearly twice that of persons who were separated, widowed, or divorced (17.4%) and of nevermarried persons (14.4%).”

(In contrast, unmarried people tend to be more engaged in political activities such as volunteering for a political party.)

Moreover, a 2018 Australian study concludes:

Parents seem to play a key role in providing a route into civic participation and encouraging our young participants to get involved – even more so than a positive experience at school or through friendships with peers. The data we present undermine the idea that strong families do not contribute to civil society – and suggest instead that strong bonds forged within the family can lead to linkages outside it.

Much of the contribution from married couples with children in this regard can be described as “accidental.” That is, as Caputo notes, the process of raising and educating children tends to simply thrust families into more social and interconnected roles within the community. Moreover, married couples with children tend to move around less, therefore contributing to more stable neighborhoods and communities. For one, married parents stay together longer than unmarried co-habiting couples. The relative longevity of married parents leads to more stability for the home lives of children. Even when adjusted for income, high levels of residential mobility are associated with “negative outcomes including suicide attempts, criminality, psychiatric disorders, drug abuse, and unnatural mortality.”

Moreover, a study for the US Department of Housing and Human Services found, “twice as many single-parent families moved compared with two-parent families (26 percent and 13 percent, respectively).” The presence of children often encourages married parents to avoid even short-distance moves. Parents may be instinctively concluding what other research has shown—namely that frequent moves lead to disruptions in a child’s life and correlate with negative social outcomes.

The Link Between Families and Religion

Like families, religious institutions—at least in the West—have offered competition for state institutions and have been central to the independence of civil society. The key building block of religious institutions have been families with married parents.

For example, a substantially larger portion of married people attend religious services compared to never married and separated/divorced adults. This is reinforced when children enter the equation.

A number of studies show a sizable overlap, in terms of behavior and lifestyle, between married people and religious people. This is because married people tend to be religious and vice versa. As summarized by Hanna Seariac:

Additionally, married people are generally more likely to be religious and stay religious.

Both religion and marriage have demonstrable benefits. Research shows actively religious people tend to be happier, more civically engaged, participate in more communities, report some health benefits and engage in more philanthropy. Marriage has benefits for individual couples and their children, but also is instrumental in creating economic stability. ...

Researchers have discovered that children who grow up in a single-parent household are more likely to disaffect from their religion and less likely to attend religious services. ... As children observe the rupture of their parents’ marriage, they become less likely to be religious growing up and more likely to either not marry or have an unstable marriage.

There is a feedback loop here. While marriage a and child-rearing leads to more civic engagement, much of that engagement involves volunteering for religious institutions and related charitable organizations. This, in turn, encourages more and continued engagement between these married people and their religious institutions overall.

Data has also shown that those people who regularly attend religious services tend to be married more often and experience much lower rates of divorce. This leads to longer marriages, which in turn leads to more volunteering and community engagement, and so on.

Political Views of Married People and Religious People

Increased non-political civic engagement among married people likely reflects an ideological bent that is more skeptical of state power.

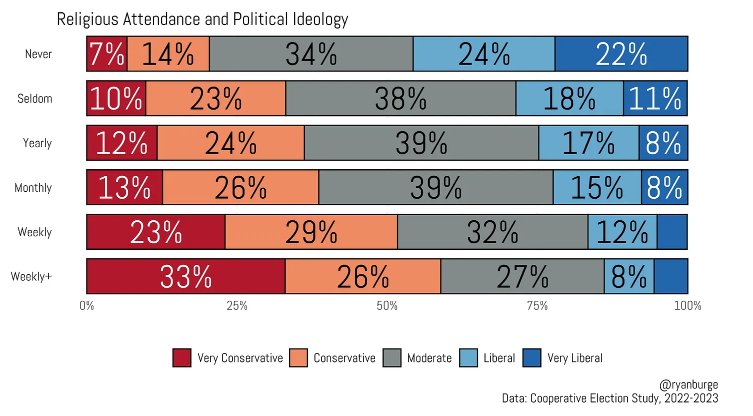

In his research on attendance at religious services, Ryan Burge concludes “There is almost no ‘liberalizing religion’ in the United States ... The more people attend [church], the less liberal they are.” (”Liberal” in this context means “leftist” or “progressive” or “social democrat.”)

Among those who attend weekly or more than weekly, no more than 16 percent identify as “liberal” or “very liberal.” Nearly 60 percent of those who attend religious services more than once a week identify as conservative or “very conservative.” This correlation is so solid it even cuts across racial categories.1

What do these conservatives believe? Well, for our purposes here—i.e., looking at family as a non-state institution—a 2021 Pew survey shows that people who self-identify as conservatives tend to overwhelmingly agree with the statements “government is almost always wasteful and inefficient,” and “government is doing too many things.” In contrast, the opposite is true for those who self-identify as “liberal” and lopsidedly disagree that governments are too wasteful and powerful.

At the same time, married people more often tend toward self-identifying as “conservative.” This leads to the so-called “marriage gap” in which there is a sizable difference between political views of the unmarried and the married—especially among women. Unmarried women tend to lean well to the left of married women, and adhere to a far more positive view of an activist state.

It’s easy to see why states and their agents have for so long sought to weaken families and related institutions. Without strong families at the center of civil society, many other non-state institutions are weakened as well, and state institutions like public schools and welfare programs become far more central to the lives of many.

- 1

An additional dimension to this can be found in how conservatives tend to report higher “relationship quality.” See Troy L Fangmeier, Scott M Stanley, Kayla Knopp, Galena K Rhoades, ”Political Party Identification and Romantic Relationship Quality,” Couple Family Psychol 25, No.9 (Jun 2020) (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8266382/)