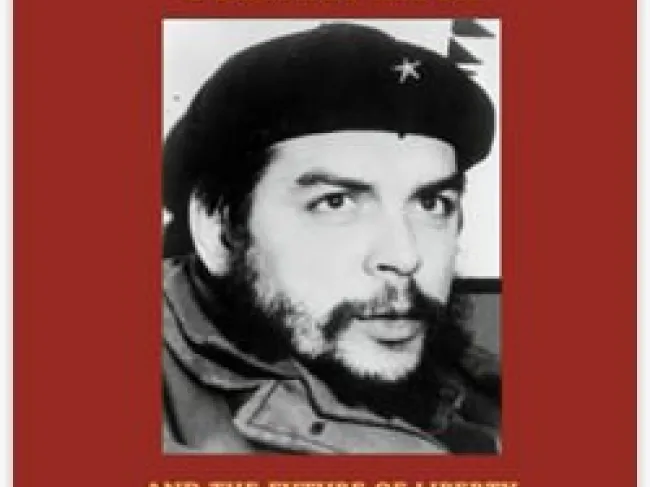

[The Che Guevara Myth and the Future of Liberty by Alvaro Vargas Llosa • Oakland, CA: The Independent Institute • 2006.]

Ironically, anticapitalist crusader and left-wing icon Che Guevara has turned into a brand name revered by people the world around, which brought me to Alvaro Vargas Llosa’s The Che Guevara Myth and the Future of Liberty. Llosa, who is a senior fellow at the Center on Global Prosperity at the Independent Institute, has combined three previously published articles into a short (67 page) book that evaluates the Guevara legacy and assesses the prospects for liberal reform in Latin America.

The essays stand alone. While Llosa offers a critical dismantling of the mythology surrounding Che Guevara in his first essay, he does not connect the Guevara legacy directly to modern Latin American liberalism. He offers a complete discussion of the reforms, both liberal and illiberal, that have taken place in Latin America over the last several decades, and a treatment of the history and legacy of individualism in Latin America.

Llosa introduces the book with an anecdote about how he first realized that something might have been amiss when he saw a poster of Che Guevara on a friend’s wall next to “a picture of ‘Comrade Gonzalo,’ the genocidal leader of Shining Path,” a Maoist organization in Llosa’s native Peru (p. 2). Gonzalo was a tyrant whose wrath had affected Llosa “firsthand.” His goal is to right wrongs and correct falsehoods as he sees them, arguing “that intellectual and political deceit — the bondage of the mind — represent the first step toward oppression” (p. 4). Thus he embarks on an exploration of the mythology of Che Guevara and the tradition of liberalism in Latin America.

Llosa argues that Guevara replaced Batista’s tyranny with his own. After taking Havana, “Guevara murdered or oversaw the executions in summary trials of scores of people — proven enemies, suspected enemies, and those who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time” (p. 11). Guevara slaughtered some of his enemies and tortured others by simulating executions (p. 11). During his time in charge of La Cabana prison, Guevara oversaw numerous summary executions (p. 12–13). “Counterrevolutionaries,” dissidents, and others were sent to a hard labor camp for “crimes against revolutionary morals, to a lesser or greater degree,” in Che’s words (pp. 16–17).

This laid the foundation for forced internment of unfavored groups. Hardly a peace lover, Guevara also made noise about nuclear war “to defend a principle” and war more generally between countries (p. 18). Fine work and words for someone whose likeness “adorn(s) Mike Tyson’s abdomen” (p. 22).

The essays on Latin American liberalism complement the research program exemplified in the work of Hernando de Soto. Llosa takes a critical look at the cultural and political institutions that have stood in the way of liberal reforms or distorted reforms for private gain. Many of the liberalizations that occurred after the failures of collectivism in Latin America were very poorly done: many assets were transferred into the hands of politically connected elites, and these favored firms were often granted monopoly privileges. This has created popular resistance to further liberalization (p. 37–38). As Llosa writes, “[i]nstead of distributing property ownership widely, as happened in England and in certain central European countries, privatization in Latin America served to close the tight circle of wealth” (p. 37). Even the celebrated Chilean education reforms are limited because “the state still controls the curriculum” (p. 47).

Many libertarians correctly points out that the botched “privatizations” that have occurred in Latin America, Eastern Europe, and elsewhere have been transfers of resources to favored constituencies. People view these episodes as products of free-market capitalism; therefore, the ensuing morass has contributed to a global antiliberal backlash which, I fear, will convince many that the political mayhem following some forms of liberalization is part of the logic of capitalism.

Llosa reinforces a lesson for everyone, whether they be students, seniors, intellectuals, or policy makers: humility in advocacy and respect for local customs is of paramount importance. I, for one, have spent precious little time in Latin America and am therefore ill equipped to design a program that will lead to peace and prosperity unto time immemorial. Attempts by well-intentioned technocrats of all persuasions have had disastrous results. Beyond general principles like private-property rights, we should leave the details to people who know what they’re doing. Local knowledge matters, and the people who live their day-to-day lives in the shantytowns of South America are in a much better position than any well-intentioned outsider to make decisions about their welfare.

Austrian Economists T-Shirts:The Full Collection

Austrian Economists T-Shirts:The Full CollectionWhile browsing for some stuff about Che Guevara for a project about human-rights violations and economic freedom last summer, I came across www.che-lives.com. Three things about the site immediately jumped out at me. First, the hammer-and-sickle icons on the left sidebar, the second of which is next to “advertising” (by Google — the link will take you to cheguevaraproducts.com). The second is the fact that the right sidebar is all links to the Che-Lives Store. Then, right below the middle of the page are “Links” (actually “Ads by Google” again) with one offering “Che Guevara Shirts” and the other linking to “10 Rules of Flat Stomach” (can’t I just cover unsightly flab with a Che shirt?). From the main site, it would be easier to navigate to “10 Rules of Flat Stomach” than it would be to actually find anything Che said or wrote.

Beautiful irony, thy name is Che Guevara.

[bio] See his [AuthorArchive]. Comment on the blog.

This article is based on a post of the same title that appeared on Division of Labour in August 2008.

You can subscribe to future articles by [AuthorName] via this [RSSfeed].