The Bureau of Labor Statistics this morning released new revised benchmark payroll totals used for estimating employment in the United States. The new revisions adjusted payrolls, for the year-long period ending in March 2025, downward by 911,000. That’s the largest downward revision on record, and the biggest since 2009, in the midst of the Great Recession. (The final figures for the period are due early next year.)

Bloomberg reports:

Before the report, the government’s payrolls data indicated employers added nearly 1.8 million total jobs in the year through March on a non-seasonally adjusted basis, or an average of 149,000 per month. The revision showed average monthly job growth was roughly half that.

In other words, during most of 2024, and into early 2025, the regime and the media were repeatedly reporting “blowout” six-figure job gains, while the real average monthly job gains were closer to 75,000 per month. In other words, the job market was considerably weaker last year than was reported.

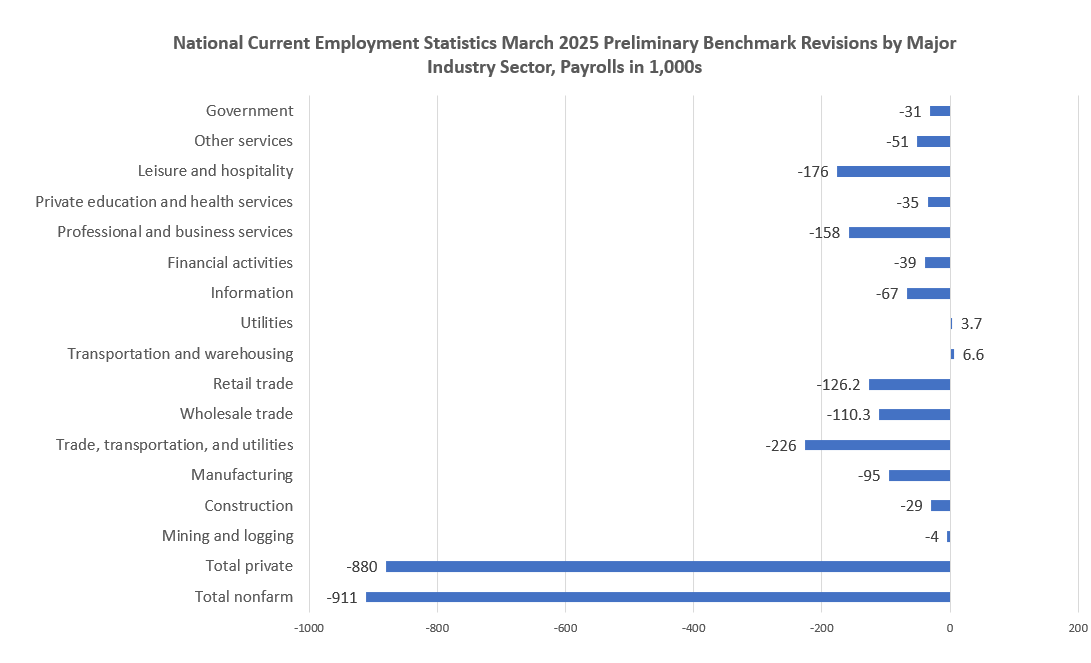

Blooomberg goes on to note that “Payrolls were marked down in nearly every industry and most states.” Significantly, private payrolls were revised downward by 880,000 for the period, led by large downward adjustments in wholesale trade, retail trade, professional and business services, and leisure and hospitality.

This latest negative revision is the second year in a row in which monthly jobs data has had to be revised downward in a big way. For the year ending March 2024, the benchmark payroll revision was negative 818,000, making it the second largest downward revision since 2009. Moreover, for the period ending March 2023, the downward revision was 306,000. In total, that’s over two million imaginary jobs that were included in monthly jobs estimates throughout those years, but which later disappeared.

Rewriting the Narrative

Although nearly all of this job growth has proven to be totally illusory, the imaginary “blowout” jobs numbers were key to an ongoing narrative that was used repeatedly throughout 2024, and has been used even up until July of this year.

We see how this narrative was crafted by complacent and credulous economists, pundits, and reporters. We can note how the message of a “strong jobs market” was pushed repeatedly using the job growth numbers that we now know were false.

Moody’s economist Mark Zandi, for instance, repeatedly referred to the economy as “picture perfect“ throughout much of 2024, and we now know he was basing this rather fanciful assessment on deeply inaccurate job growth numbers that were often double the real number. At the Washington Post, finance reporter Heather Long gushed month after month about “blockbuster“ jobs reports and about how they just kept “surpassing expectations.” It turns out those numbers were made up, but Long lacked either the honesty or the skill necessary to see the reality behind the numbers. As late as mid 2024, Long and the Post staff were still repeating the inflated jobs numbers which fueled the claim that the Biden economy had produced six million new jobs over pre-pandemic levels as of mid 2024. Again, those factoids were based on made-up BLS numbers.

The Trump administration, which is only skeptical of jobs numbers when they don’t favor Trump, uncritically accepted inflated numbers as well. For March 2025, Trump’s Labor secretary Lori Chavez-deRemer declared “WE BLEW IT OUT OF THE WATER ... which smashed expectations amid explosive private sector growth.” It turned out those numbers were hugely inflated.

Among ordinary people, however, the general mood remained significantly less jubilant than that expressed by the uncritical pro-regime economists. Disconnect between public sentiment and the official jobs estimates led to an entire subgenre of articles in major media outlets lecturing us about how the economy is much better than the public thinks it is.

“The US Economy Is Doing Better Than Americans Think“ lectured one headline from Newsweek. Boston Public Radio harangued its listeners about their lack of appreciation for the supposed blockbuster economy: “You may think the U.S. economy is in bad shape. But that’s not the case.” City Journal interviewed the editor of The Economist, Simon Rabinovitch, in late 2024 with the headline “The USA Economy Is Strong, but Americans Remain Skeptical.” Rabinovitch declared “recently America has been generating about 150 to even 300,000 new jobs per month.” That number, it turns out, was more than double the real number.

Throughout all these articles, the authors and editors kept asking themselves: “why do these stubborn, ignorant Americans not see how wonderful the job market is?” Well, perhaps one reason the public didn’t appreciate all that “blockbuster” job growth was that it didn’t exist.

Through all these months of imaginary six-figure job growth, the Federal Reserve’s economists also repeated the lie, insisting month after month that the job market was “solid.” Although the Fed’s Beige Book data increasingly showed a stagnating economy, the reality of that “anecdotal” data was dismissed as contrary to the BLS payroll numbers which, of course, showed “blowout” job gains.

Wall Street hasn’t shown any more discernment than the Fed or the finance pundits. For the past two years, every time the BLS releases a new report “exceeding expectations,” the market rallies on the official claim that the economy must be in great shape.

But the Unemployment Rate Is Low!

At this points it’s abundantly evident that the establishment/payroll survey is utterly unreliable, at least in initial estimates. Later estimates appear to be more trustworthy, but those numbers come in many months after the end of the month in question. Clearly, using the initial estimates to construct any sort of narrative about the current state of the economy is folly. It’s even worse to try to craft public policy based on this same data.

But what about the other survey of employment? There are two employment surveys, of course, with the other one being the household survey on which the unemployment rate is based. While the payroll survey is a survey of jobs—including part time jobs—the household survey is a survey of persons. So, many pundits and politicians and policymakers may continue to insist that the economy is going gangbusters because the unemployment rate, as calculated by the household survey, looks “great.” Unfortunately, beyond the headline unemployment rate, the household survey doesn’t look too good either. For example, the household survey shows us that the number of discouraged workers has been steadily climbing since March of 2023. The total now stands at 6.3 million,. Those workers aren’t even included in the calculation of the unemployment rate, so the unemployment rate is underestimating the actual number of workers out there who are unemployed and would accept a job if they could find one. Moreover, the number of unemployed workers that are included in the unemployment rate has also risen, and is now up by more than 1.2 million workers over the past 18 months. So why hasn’t the unemployment rate gone up? It’s because the labor force participation rate has gone down. (The household survey also tells us the employment-population ratio is at a ten-year low, excluding the covid period.) At the same time, the number of workers needing second jobs has surged as wages have failed to keep up with price inflation over the longer term. The total number of “multiple job holders” across a variety of categories has risen to thirty-year highs over the past 18 months. When it comes to actual growth in the number of employed people, the household survey doesn’t provide much good news either. as I mentioned earlier, the employment level has fallen by 500,000 workers since January 2025.

But at least the household survey numbers are more reliable, right? Not quite. A perusal of household survey numbers over the past year will show a very large and odd surge in the total number of employed persons in January 2025. That’s not an artifact of real employment growth, though. It’s a big revision to estimates of the population size. As the BLS noted at the time: “This year’s adjustment was large relative to adjustments in past years. It reflects both updated methodology and new information about net international migration in recent years...These annual population adjustments can affect the comparability of household data series over time.”

Translation: household survey numbers are subject to big revisions also, and the numbers must all be taken with a huge grain of salt especially when making comparisons over time.

We Can’t Use Government Employment Numbers for Central Planning

Well, if you’ve managed to make it this far, reading through all these details about revisions to government reports, there’s an important lesson that we can take away from all of this: the idea that we can centrally plan an economy, or make real-time pronouncements about monetary and fiscal policy based on monthly government reports, should be regarded as pure fantasy.

The mega-revisions to the payroll numbers over the past two years has made it more clear than ever that it is absurd to accept the federal jobs report as an accurate picture of the previous month’s employment situation. Recent revisions show that if the government reports 200,000 new payroll jobs in any given month, the actual number could just as easily be 100,000, or maybe even 10,000. The number might even be negative. And yet, we’ve all grown accustomed the dog and pony show in which the BLS releases a new jobs number and then the politicians and pundits and financial “experts” start talking about how that number tells us how the central bank should set its policy interest rate. Or the politicians might claim that the latest jobs number proves the US is in the midst of a “historic” period of prosperity. And then, a few months later, that number, on which the “experts” are basing their policy schemes, is revealed to be some other number entirely.

This isn’t to say that it would be possible to centrally plan an economy if the initial monthly jobs estimates actually were accurate. As Ludwig von Mises has shown, central planning is impossible no matter how good the government reports are. Yet, even if the monthly jobs numbers were pinpoint accurate with the first try, month-old aggregated statistics can’t possibly tell us what the “correct” interest rate is, or how much deficit spending is optimal.

Central planning has always been a fantasy, and its even more fantastic when the government statistics are so thoroughly wrong for so long.