If we are to take the official unemployment rate as the final word on the employment situation—as Fed Chairman Jerome Powell instructed us to at last month’s FOMC press conference— then we’re likely to conclude that the job market is still red hot. After all, at 4.2 percent, the July unemployment rate suggests that the US economy is at what the technocrats call “full employment.” But at the same time, there is mounting evidence that people are running out of money to spend—and that would seem to clash with the idea that the economy is at full employment.

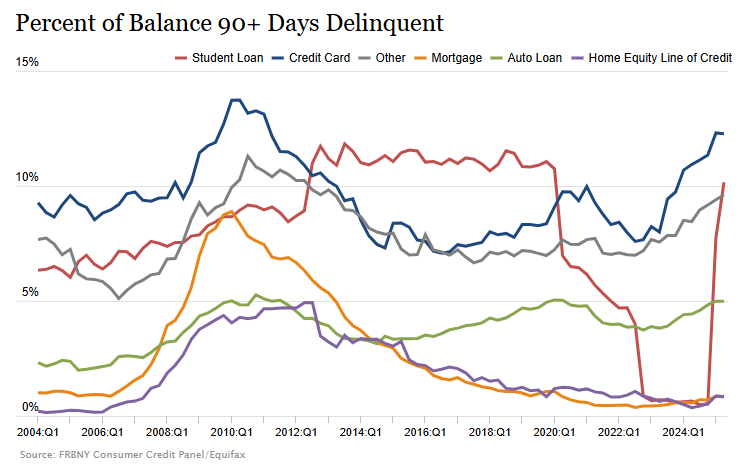

For example, the most recent three months of the Case-Shiller home price report has shown the index is in negative territory. Moreover, delinquencies in credit cards, auto loans, and student loans are at the highest levels since the Global Financial Crisis.

In another development this week that should be taken as a red flag about household budgets, McDonalds restaurants have announced price cuts. Specifically, CNN reports:

McDonald’s is slashing the prices of its combo meals just a few weeks after the CEO publicly admitted that its menu has gotten too expensive and pledged to fix the problem. ...

McDonald’s will also expand its combo offerings with a $5 breakfast deal and an $8 Big Mac and McNugget special in the coming months with the reintroduction of the “Extra Value Meals” branding.

Now, why would McDonalds need to slash prices if the US economy is in state of full employment? Why would auto loan delinquencies be at fifteen-year highs with a job market in such excellent shape?

The likely answer is that consumers simply don’t have the funds to cover both large auto-loan payments and expensive takeout meals anymore. Until recently, they did have the money to do it, as suggested by the fact that until late 2022, auto-loan delinquencies were going down. 2022, of course, was when we saw CPI inflation rise to 40-year highs. Even then, consumers didn’t seem to care that McDonald’s prices soared from 2022 and into 2023. It wasn’t until mid 2023, about the time when a social media post about an $18 Bic Mac Value Meal when viral, that consumers may have started to scale back fast-food spending.

The consumers who spend freely without care appear to be getting more and more rare in the year 2025. This should hardly be unexpected given the ongoing downward trend in the employment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

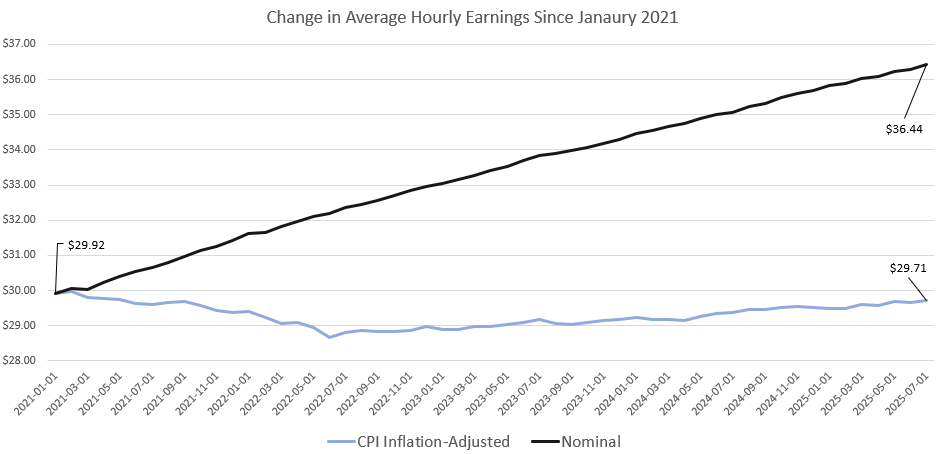

For starters, we can observe that real wages, adjusted for CPI inflation, are still below where they were in 2021. In early 2021, average hourly earnings were at $29.92. Since then, average earnings adjusted for inflation has gone down to $29.71. In other words, there has been no average real wage growth in more than four years.

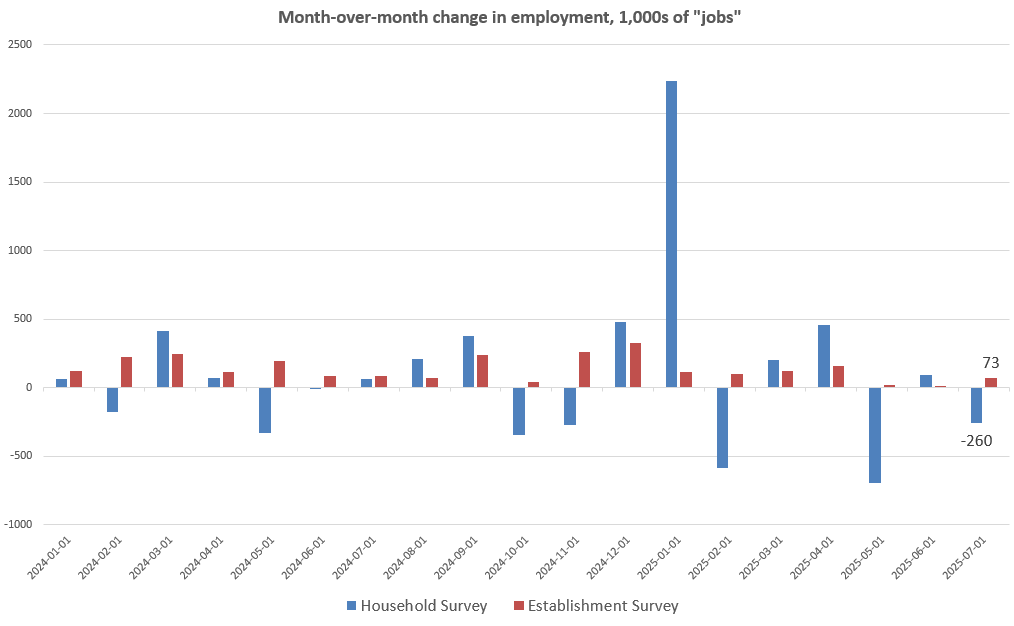

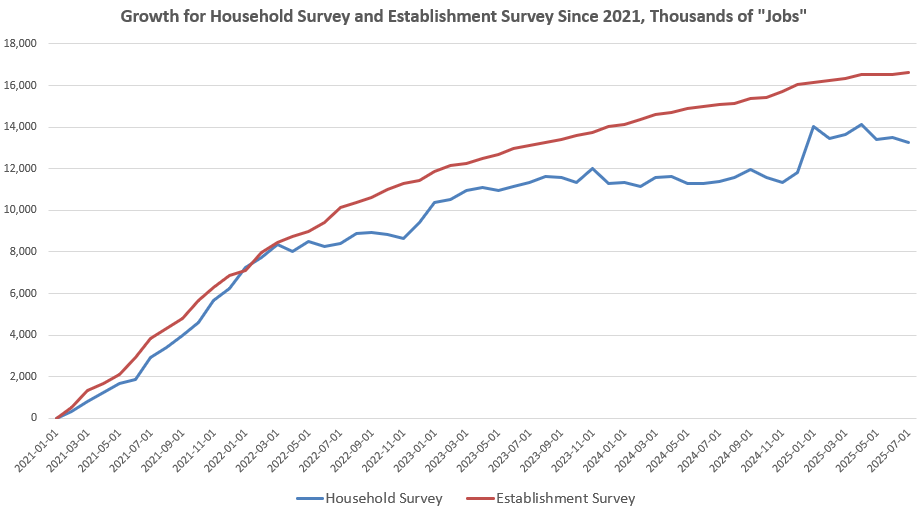

Moreover, recent monthly data on job growth has been lackluster at best. Over the past three months, total employment (according to the payroll/establishment survey) has largely flatlined, increasing by only about 35,000 per month from April to July. (Since April, total payroll employment has increased by only 0.06 percent.) After enormous downward revisions to payroll totals for recent months, the July report showed total payroll employment growth was only 19,000 in May, 14,000 in June, and 73,000 in July. These indicate a substantial slowdown in job growth.

The other measure of employment, the so-called household survey, shows that employment has fallen over the past three months, dropping by 853,000 employed persons since April. In July, the household survey showed a drop of 260,000.

The gap between the household survey and the establishment survey stems in part from the fact that the establishment survey tracks only jobs—both part time and full time—while the household survey tracks employed persons. So, these reports could show ongoing growth in total jobs that are largely part time, while the total number of employed persons remains flat.

Given that real wages are flat, this could be a situation of workers taking on additional jobs to make ends meet. This theory is backed up by the fact that part-time job growth has been outpacing full-time job growth since 2021. Full time work has increased by 7.6 percent since early 2021 while part-time work has increased by nearly 16 percent. In July specifically, full-time work was down by 440,000 jobs, from June to July, and part-time work was up by 247,000 over the same period.

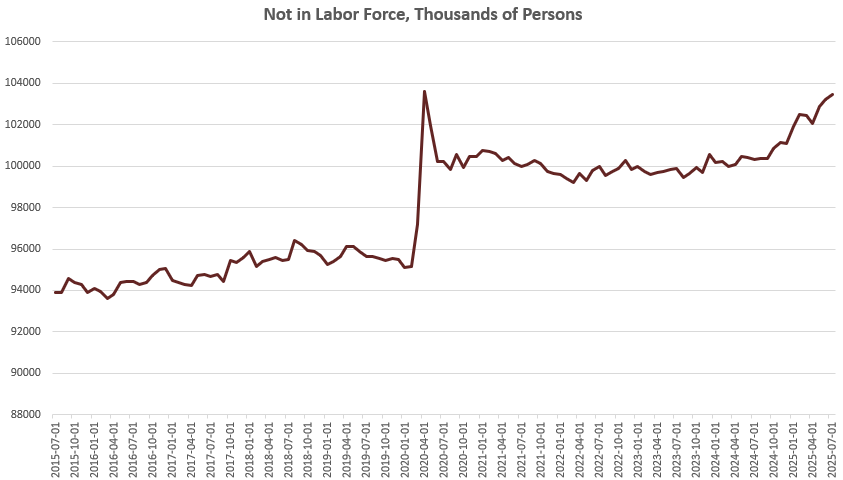

This all suggests that the job market isn’t quite as hot as both the central bank and the administration are suggesting. For example, during his most recent press conference, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell insisted that the employment situation was excellent, but said that the Fed is basing this assessment primarily on the unemployment rate. It makes sense that Powell would say this, of course. The unemployment rate, taken in isolation, presents a far rosier employment situation than does job growth and earnings data. The strong jobs picture presented by the unemployment rate is belied, however, by the fact that the labor force participation rate dropped to a 33-month low in July. That is, the reason the unemployment rate continues to appear low is the falling number of total workers. So long as workers are leaving the work force, the total number of jobs can fall, and the unemployment rate will still remain stable. Not coincidentally, the number of potential workers now listed as “not in the labor force” has surged by 1.3 million since April, and is now almost back to the peak experienced during the covid lockdowns. Without this exodus of workers, the unemployment rate would be considerably higher.

At least some policymakers at the Fed have noticed this trend. In the July minutes from the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee, released this week, employment stagnation was a topic of conversation:

In their discussion of the labor market, participants observed that the unemployment rate remained low and that employment was at or near estimates of maximum employment. Several participants noted that the low and stable unemployment rate reflected a combination of low hiring and low layoffs. Some participants observed that their contacts and business survey respondents had reported being reluctant to hire or fire amid elevated uncertainty. Regarding the outlook for the labor market, some participants mentioned indicators that could suggest a softening in labor demand. These included slower and more concentrated job growth, an increase in cyclically sensitive Black and youth unemployment rates, and lower wage increases of job switchers than job stayers. Some of these participants also noted anecdotes in the Beige Book or in their discussions with contacts that pointed to slower demand. Furthermore, a number of participants noted that softness in aggregate demand and economic activity may translate into weaker labor market conditions, as could a potential inability of some importers to withstand higher tariffs.

This “no hire/no fire” job market now appears to be playing out broadly in the economy. While it’s true we are not seeing major layoff events, we’re also not seeing much in the way of new hires.

Now, as I write this, Jerome Powell is concluding his remarks at the Fed’s Jackson Hole conference, and the consensus is that Powell is now subtly suggesting that weakness in employment will require a reassessment in the Fed’s stance on interest rates going forward. Translation: Powell is saying that the economy has weakened to the point that the Fed now may want to force down interest rates in hopes of stimulating more job growth.

I don’t know if Powell actually believes this, and one can never be sure how much Fed messaging is based on honest analysis, and how much is just regime propaganda. In any case, Powell’s claim that the weakening job market requires more monetary stimulus would certainly fit with the BLS data that Powell casually waved off a few weeks ago. It’s all a reminder that one should never take what Fed mouthpieces say as reliable insights into present or future economic trends.