The “true money supply” measure is a measure of the money supply pioneered by Murray Rothbard and Joseph Salerno and is designed to provide a better measure than M2. The Mises Institute now offers monthly updates on the TMS metric and its growth.

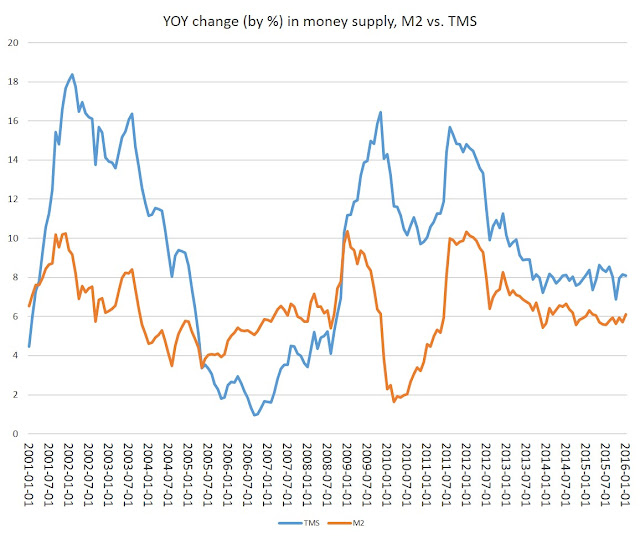

In January 2016, money supply growth, according to the TMS metric, increased 8.1 percent, year over year. That means’s the growth rate didn’t change in any meaningful way from December to January. The year-over-year change for December was also 8.1 percent. Growth was up slightly from October and November, but in the big scheme of things, growth has generally been flat around 8 percent over the past year:

M2 growth rates have also been flat over the past year, albeit at a lower level.

Unlike M2, TMS includes treasury deposits at the Fed as part of the money supply, and overall, money supply growth continued to be affected by increases in these deposits. TMS money supply growth would not be as robust, and would be on more of a downward trajectory, if treasury deposits were not growing so quickly.

In fact, in recent years, Treasury deposits have been hitting new highs. Here are the numbers (in billions of dollars):

For decades, treasury deposits remained at consistent levels, but since the financial crisis, treasury deposits have surged again and again. Today, they are now a significant factor in the movement of the total money supply, and have become an increasingly large factor over the past year.

Treasury deposits at the Fed represent the “working balance” reflected in spending and tax revenues. But why have they increased so much in recent years?

There are several reasons for this. One is the fact that the federal government now uses its accounts at the Fed to deal with political uncertainty with the budgeting process. But, another may be the fact that the Fed has been giving billions of dollars to the Treasury. In other words, the Fed’s monetary policy has become much more intimately connected to the Treasury in recent years. David Howden recently noted this issue in a column at mises.org:

The federal government paid out $223 billion in interest payments last year. The Fed remitted almost $100 billion back, leaving the net interest expense at around $125 billion. It’s not just historically low interest rates that are making it easier for the Treasury to borrow in a way that, if it were done by anyone else, would classify them as subprime. The Fed is also chipping in and helping out where it can...

In more “normal” times (i.e., prior to 2008) around 10 to 15 percent of the Treasury’s interest payments were paid back to it by the Fed. This figure has grown to almost four times that amount [up to 45 percent] over the past seven years and it doesn’t look like this trend will abate anytime soon.

With the economy weakening and deflationary pressures mounting, this close relationship between the Fed and the Treasury has proven to be an easy way to increase the money supply.