Note: The vote totals have been updated as of 9 pm EST, November 9. (Updated again at 1pm EST, November 10)

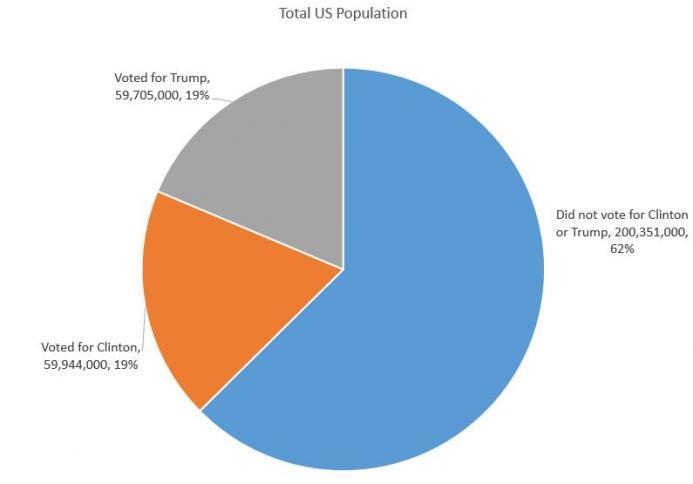

According to the popular vote-count provided by The New York Times, Donald Trump, as of today, has received 59,705,000 votes. Hillary Clinton, who won the popular vote, but not the electoral college, has received 59,994,000 votes.

At the time of the election, it is estimated there were 231,556,000 eligible voters.

This means Trump won the electoral college with votes from approximately 26 percent of eligible voters. Hillary Clinton also received votes from approximately 26 percent of eligible voters. 48 percent of eligible voters, however, abstained from voting for either Trump or Clinton.

In other words, 74 percent of eligible voters did not vote for the winner.

In a post yesterday, I looked at this same phenomena in a larger historical context. While Trump won solidly in terms of the electoral college, he won with a small minority of the eligible voter population. This would have been the case even if Trump had won the popular vote.

The numbers become even smaller when we look at how many votes he received as a proportion of the population overall. In this case, Trump won votes from only 19 percent of the overall population.

There is nothing unique about these numbers, however, when compared against other elections.

In 1992, Bill Clinton won with similar numbers, when he received 43 percent of all votes cast, and received votes from under 30 percent of the voter-eligible population.

Even in the largest blowout in the past 40 years — Reagan’s 1984 election — the victor won only 34% of the voter-eligible population.

Also notable is the fact that the 2016 election marks the fourth time in the past seven elections that the victor failed to break the 50-percent mark. In 1992, 1996, 2000, and now 2016, the winner has failed to win a majority of the votes cast.

None of this means the winners aren’t the winners, of course. They each won according to the rules (with the possible exception of 2000, when judges interpreted the rules to suit their own political agendas).

The fact that the winners enjoy the approval of only a small fraction of the population does become relevant, however, when it is claimed that the winner enjoys a “mandate” from the people, or if it is asserted that the “will of the people” has been revealed by the election.

Indeed, Reuters reported this morning that House Speaker Paul Ryan has declared: ”He just earned a mandate and we now just have a unified Republican government.” One might be left wondering: “A mandate from whom?” It’s certainly not a mandate from the 74 percent of eligible voters who elected to not cast a vote for him.

But, hypothetically, let’s say that Trump had managed to win an outright majority of from all eligible voters. How would this then translate into a mandate? The act of casting a vote tells us nothing about motivation or enthusiasm, so it remains possible to know what message, exactly, the voter wished to send to the candidate. It is also impossible to infer from a vote what aspects of the candidate’s platform meet each voters approval, or which aspects are a priority. An unemployed auto worker from Ohio is likely to vote for Trump for very different reasons than a college educated suburbanite from Colorado. Claims that both of these votes can be combined to fashion a single “mandate” for the candidate strains the bounds of credibility.

Ryan McMaken is the editor of Mises Wire and The Austrian. He is the author of Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre. Contact: email, twitter.