According to the most recent data, the birth rate in the United States hit a new low in 2024. Many pundits and economists across the political spectrum have framed this as a big problem, not least of all because regime supporters want more young taxpayers to prop up social-benefit programs like Medicare and Social Security.

Among both leftists and conservatives, it has become popular to insist that a few tweaks to economic policy will reverse the downward trend in fertility.

For example, conservatives in recent years have pushed for a new federal program providing paid parental leave. On the Left, activists have repeatedly claimed that more healthcare spending on children and families will increase fertility rates. Both sides have claimed that new policies designed to reduce housing costs will increase the fertility rate. The idea here is that net spending power will lead to more children.

On the surface, it makes a lot of sense to assume that more net income makes child rearing cheaper—and consequently more people will have children. Unfortunately for this idea, experience in recent decades suggests there is actually a relatively weak connection between rising incomes and birth rates. That is, it is increasingly clear that the phenomenon of falling birth rates is due to factors that are apparently far beyond the mere cost of living. Moreover, deliberate efforts to create state-funded benefits for childrearing activities have failed to increase fertility rates.

Can More Family-Targeted Welfare Increase the Fertility Rate?

It has become popular among pro-fertility activists to say that government policies favoring increased benefits for parental leave, childcare, and childrearing will increase fertility. But where has this been demonstrated? It certainly has not been demonstrated in modern European welfare states.

For example, advocates for parental leave like to point to the proliferation of paid family-leave programs in Europe. Some advocates even claim that these policies make family life more affordable, and therefore good for fertility rates. Even if that’s true, it is apparent that paid family leave programs can’t be shown to increase fertility rates on their own. After all, most of the countries boasting of paid family leave programs have fertility rates below that of the United States, and all these countries have followed similar downward trajectories in fertility over more than fifty years.

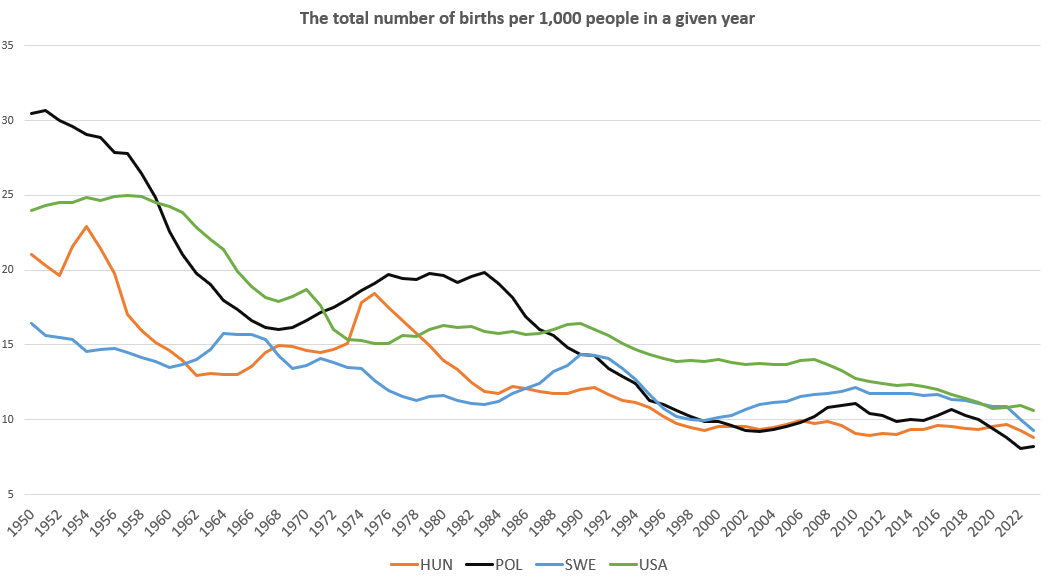

A specific case that we might point to is Sweden where we have long been told that the welfare state favors generous spending on child care and early-childhood education. This, we are told, reduces the cost of childrearing. Again, the policy does not appear to work, and the Swedish fertility rate continues to fall:

The fact that it is easy to combine children with employment thanks to generous systems for parental leave and childcare is assumed to make more people inclined to actually have children. ... But as there have been no significant changes in family policy, this does not explain the downturn we now see.

But how about in eastern Europe? Conservatives like to quote family-friendly statements from Hungarian politicians who state that they’d like to support more childrearing with government policy. Since 2010, social conservative Viktor Orbán has overseen the implementation of a variety of ostensible pro-child policies such as tax credits for families with children. Women who have more than two children never pay income tax. This appeared to work for several years after 2010, but since 2021, the birth rate has fallen again from 1.61 in 2021 to 1.38 in 2024.

The overall trend is down across many countries. Source: Our World in Data.

Meanwhile, in Poland, the state has recently implemented similar tax bonuses designed to increase fertility. Overall economic trends suggest this won’t turn the tide. After all, since the end of the Cold War, Poland has been one of the world’s great economic success stories, and since 1990 “GDP per capita in Poland has risen eightfold, even adjusting for the cost of living. Since 2002, unemployment has fallen from 20% to 2.8%.”

Yet, in Poland, the fertility rate has now fallen to 1.1, making Poland one of the least fertile countries in the world.

Are we really to believe that some tax credits will succeed at doing what an eight-fold increase in income could not do?

A similar trend exists in Hungary, by the way, where real GDP per capita has risen by 40 percent since 2012, yet the fertility rate is still below where it was during the bad old days of the Cold War.

The Broader Historical Experience: Industrialization and Falling Birth Rates

Further evidence of a weak link between fertility and economic prosperity is found in a new NBER working paper released by Claudia Goldin.1

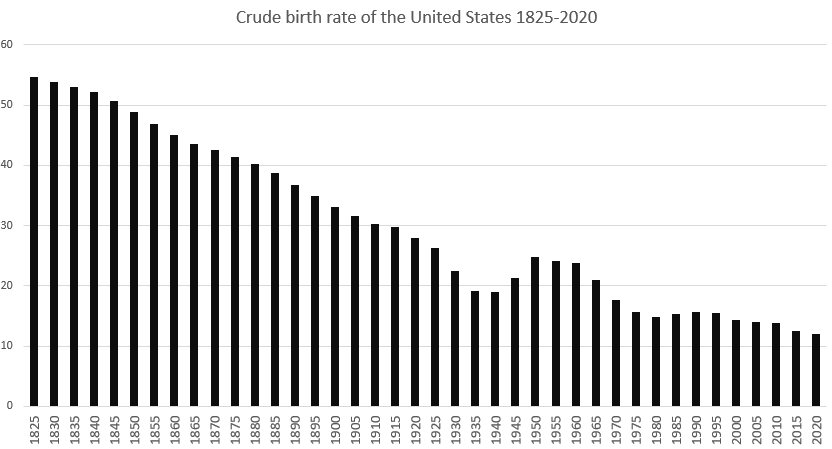

Goldin notes that fertility in the United States fell throughout most of the nineteenth century, just as standards of living were increasing substantially. Moreover, the decline continued into the first forty years of the twentieth century, with a trend solidly in place well before the Great Depression.

Nearly 200 years of falling fertility. Source: Statista.

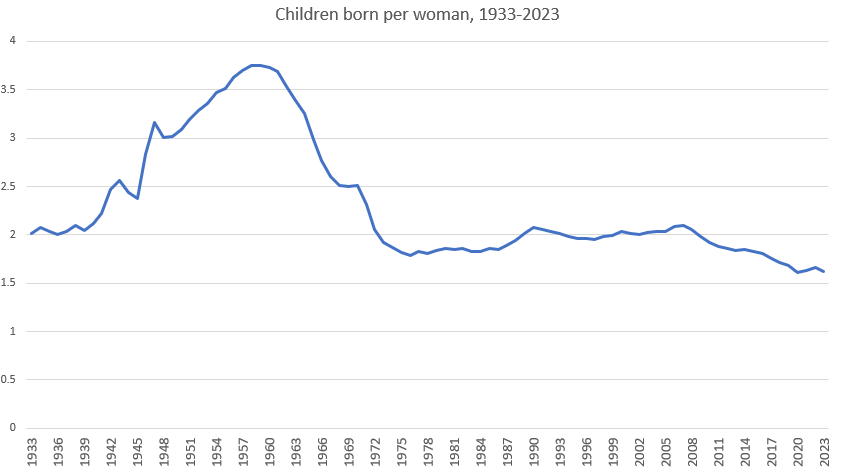

When most Americans comment on fertility rates, however, they tend to look only to post-1945 rates, and to look at falling fertility since the 1950s. Yet, as Goldin correctly points out, the “Baby Boom was an astonishing turnaround from the low birthrates of the 1920s and the Great Depression.” That is, the rising fertility of the early 1950s was very much a departure from the long-term trend.

Source: Our World in Data.

The US is not alone in this trend, the so-called “fertility transition.” In France, according to some research, the transition occurred “at the latest in 1827 (other data suggests the transition happened at least two decades earlier).”2

Life was hard in the nineteenth century, of course, and the indisputable fruits of industrialization were felt only gradually, even if solid gains in income and standards of living were being made almost constantly. Nonetheless, we find that as income increased, fertility actually went down.

Moreover, we find there is little connection between fertility and anything we might call “objective” living standards. For example, the standard of living is objectively much higher today than it was during the 1920s, or even the 1970s. Cars are safer, homes are larger, food requires a smaller share of income, and clothing is much, much less expensive. Virtually no one’s great-grand parents would look at modern life and think that the standard of living was higher 50 years ago or 90 years ago. Yet, many potential parents state that they can’t have children now because it’s too difficult to maintain an acceptable standard of living. Obviously, subjective standards of what constitutes an acceptable standard of living has changed substantially from what our grandparents thought.

We find here a similar trend to what we see in Poland. Although the standard of living in Poland is clearly far above what it was in Cold War times, fertility rates continue to fall.

This clear trend then, has led one economist to recently note:

There’s lots of explanations that people have put forward in terms of why the birth rate is falling in the United States. For the most part, a lot of them aren’t particularly successful ... So people talk about things like higher costs of having a family—of raising children, housing, and child care. It turns out those don’t work very well as explanations.

So, if mere income levels and economic trends don’t provide definitive explanations of fertility, what does?

Researchers offer a wide variety of explanations from ideology to education levels. These are all debated, but the whole discussion is a helpful reminder that human action is not a product of a mechanical relationship between income levels and the cost of some good or activity. What human beings value can change substantially over time for reasons far more complex than “the price of thing X went down, so I will therefore buy more of thing X.” If having children is “thing X” in this equation, it is clear that there is much more to the matter than the cost of feeding and clothing and housing children.

- 1

Claudia Goldin, “The Downside of Fertility,” in NBER Working Paper Series, Working Paper 34268, http://www.nber.org/papers/w34268.

- 2

See Blanc, G., & Wacziarg, R. (2018). Change and persistence in the age of modernization: Saint-Germain-d’Anxure, 1730–1895.; Spolaore, E., & Wacziarg, R. (2014). Fertility and modernity.; Spolaore, E., & Wacziarg, R. (2009). The diffusion of development. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(2), 469–529.