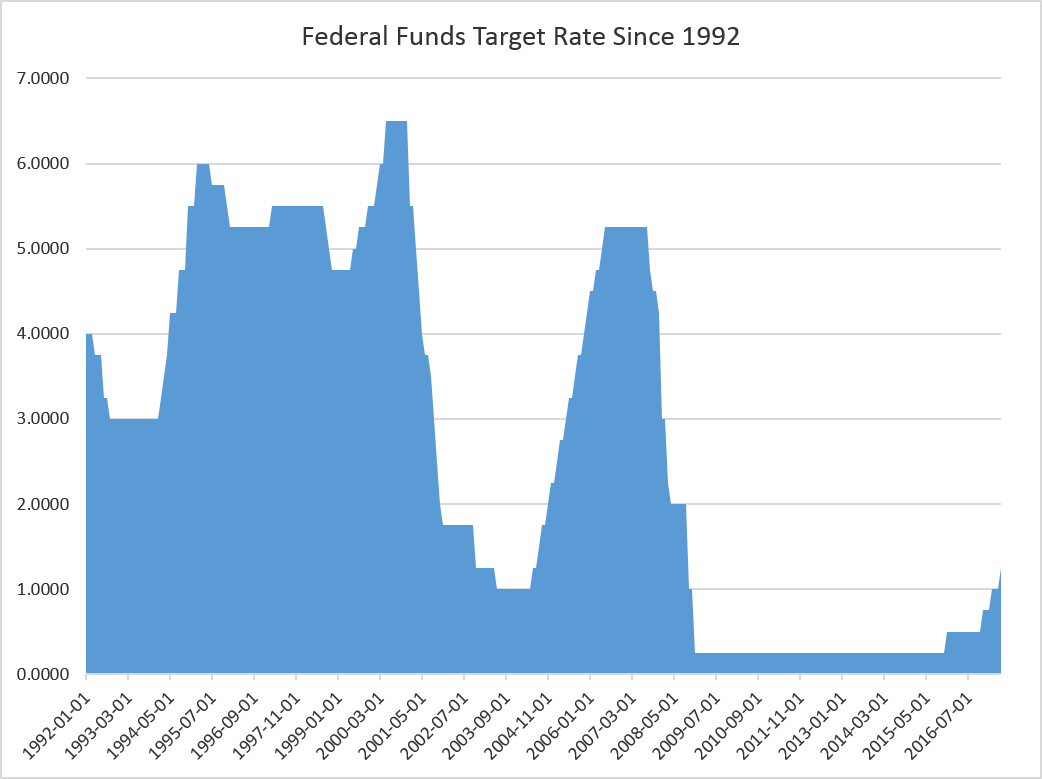

Last week, the Federal Reserve announced an increase in the Federal Funds rate to 1.25 percent. The last time the target rate reached so high was in September of 2008, when the rate was 2.0 percent. In October of that year, the target rate fell to 1.0 percent, and was moved down to 0.25 percent in December. It remained at 0.25 percent for the next 83 months.

This week’s rate increase was the third increase since December 2016, when the Fed increased the rate from 0.5 percent to 0.75 percent.

Compared to the last seven years, this policy looks hawkish by comparison. On the other hand, compared to the 1990s — which were at the time seen as an era of low rates — current policy remains remarkably accommodative.

Other central banks, however, continue to take no action.

For example, the Bank of England recent voted to keep rates at a record low 0.25 percent. Meanwhile, the Bank of Japan is making no change and keeping rates near zero. Last week, the European Central Bank kept is target rate at negative 0.4 percent. In the wake of this week’s Fed decision, the People’s Bank of China elected to take no action either.

If we look at all these central banks together, the Fed does appear to be the odd man out:

Perhaps the most notably development is the Fed’s announcement of plans to “normalize” its balance sheet and reduce in size the huge $4.4 trillion balance sheet it has accumulated since 2009. According to CNBC:

On top of the rate hike, the committee said it will begin the process this year of reducing its balance sheet, which it expanded by buying bonds and other securities in order to fight the housing crisis. Minutes from the May meeting indicated officials already had begun discussion about putting a set limit each month on the amount it would let run off as it conducts its policy of reinvesting proceeds...

Image

“The committee currently expects to begin implementing a balance sheet normalization process this year, provided the economy evolves broadly as anticipated,” the post-meeting statement said.

According to information released Wednesday, the roll-off cap level will start at $6 billion a month for the level of principal payment proceeds from Treasurys it will let run off without reinvesting. The remainder will be reinvested.

The Fed will increase that cap level at a pace of $6 billion each quarter over 12 months until the cap reaches $30 billion a month.

For agency and mortgage debt, the cap will be $4 billion a month initially, with quarterly increases of $4 billion until the level reaches $20 billion a month.

Once both targets are met, the total runoff per month will be $50 billion. Several Fed officials have said publicly they expect the runoff program to continue until the balance sheet declines to about $2 trillion to $2.5 trillion.

If the Fed manages to implement this plan, we’re still only looking at a reduction to 2010 levels, and 2010 was not exactly an age of tight money at the Fed.

Moreover, it’s rather unlikely we’ll ever see this actually happen. Bill Gross, for example, remains doubtful:

I think that the Fed can’t follow through with their ... plan and I think that the Fed can’t follow through with what they’re suggesting in terms of the sell-backs in the Treasury market.”

And why won’t the Fed follow through?

Well, as Jason Schenker points out at Bloomberg, reducing the balance sheets requires a robust economy, and it’s not clear the US has that right now. Moreover, recent history has not provided much hope in this respect:

The ECB’s attempt to reduce its balance sheet was a complete failure, and it almost resulted in a recession. Policy makers were forced to reverse course, and it necessitated the massive quantitative easing program the ECB has since been implementing since, putting the current size of the ECB balance sheet at 4.1 trillion euros ($4.57 trillion) -- more than double the level at the end of its reduction program. In other words, a one-third reduction in the ECB balance sheet subsequently necessitated its doubling from the newly reduced level. This shows how difficult balance sheet “normalization” could be for the Fed.

For all its talk of balance sheet normalization, the Fed may similarly struggle. After all, once hooked on the sauce of cheap money, financial markets don’t want to see the punch bowl taken away. If the ECB offers a lesson, it’s that shrinking the balance sheet can necessitate a rather quick, and even more drastic, expansion.

The Fed’s state itself notes its plans depend on “the economy evolv[ing] broadly as anticipated.

At this point, the Fed is clearly in a mine field. It has been seeking to raise rates for some time, to give the Fed some room to move if the economy does fall back into recession. At 1.25 percent, matters have improved, but rates are no where near where they were in 2007 (above 5 percent) at the beginning of the last crisis. However, given the weakness of the economy, it’s not at all clear that current markets could ever survive an attempt to raise rates even halfway to the five percent rates we saw a decade ago. In any case, even some minor tightening of policy is can be dangerous, as Thorsten Polleit recently explained:

To keep the boom going, the central bank must keep interest rates below their natural levels. It cannot raise them back to “normal.” First and foremost, higher interest rates would make the boom collapse. The credit market would collapse, stock and housing prices would tumble, and the financial system and the economy as a whole would go into a tailspin.

One may ask: Why is the Fed then raising rates then? Perhaps the Fed’s decision-makers think that the US economy has overcome the latest crisis and higher interest rates are economically justified. Others might wish to tighten policy for getting the short-term inflation adjusted interest rate out of negative territory.

Be it as it may, the disconcerting truth is this: Fed rate hikes will close the gap between the natural interest rate and the actual interest rate level. This, in turn, amounts to putting a brake on the boom, bringing it closer to bust. It is impossible to know with exactitude at what interest rate level the US economy would fall over the cliff.

One thing is fairly certain, though: The US economy, and with it the world economy, is caught between a rock and a hard place. Maybe the Fed’s current rate hiking spree will bring about the bust. Or the Fed refrains from raising rates further and keeps the boom going a little bit longer.