In the pursuit of market-based changes in health care, it is important to pay attention to proposals that are both fundamental and smaller, but represent a step in the right direction. The former category can include the radical deregulation of health care by abolishing monopolistic institutions like the AMA or FDA. The latter includes reducing or eliminating fraud and waste in the government’s Medicaid and Medicare programs. However, regardless of the nature of these changes, it is essential and crucial to understand the key elements of a market-based health system without which its achievement will not be possible.

Deregulation of Health Insurers

Insurance is a market institution and has nothing to do with government redistributive plans. Many people complain that insurers—through exclusions and restrictions from coverage—limit access to healthcare for those most in need. But the truth is that insurance, as an institution, was never intended to cover everyone. This is not due to the ill will of insurers, but to the specific nature of their business, which is risk calculation. Thanks to advanced methods of its calculation, it is possible to include more groups in insurance coverage. It is worth emphasizing that, without insurance, the world would not look better, and people would be forced to deal with uncertainty and allocate more resources, not less. Insurance makes uncertainty and part of the real world presentable in a more manageable form based on probability calculus.

Contrary to popular myths, a larger part of the population can be insured, which does not mean that everyone will be in one large group of insured. There are smaller or larger differences in health between people, which project higher or lower health risks. This is reflected in premiums and the extent of insurance coverage. Limitations and exclusions are not any obstacles to the right to health care, but useful tools through which insurers are able to create stable groups of insured (more on this here).

It’s also worth emphasizing the important point that freedom is also the right to limitations and exclusions, or to put it another way: freedom is not about forcing some social groups to have insurance and subsidizing other groups. Fortunately, there are a number of other solutions on the market that complement and, at the same time, to some extent, compete with the institution of health insurance.

Direct Payments and Competition from Smaller Medical Facilities

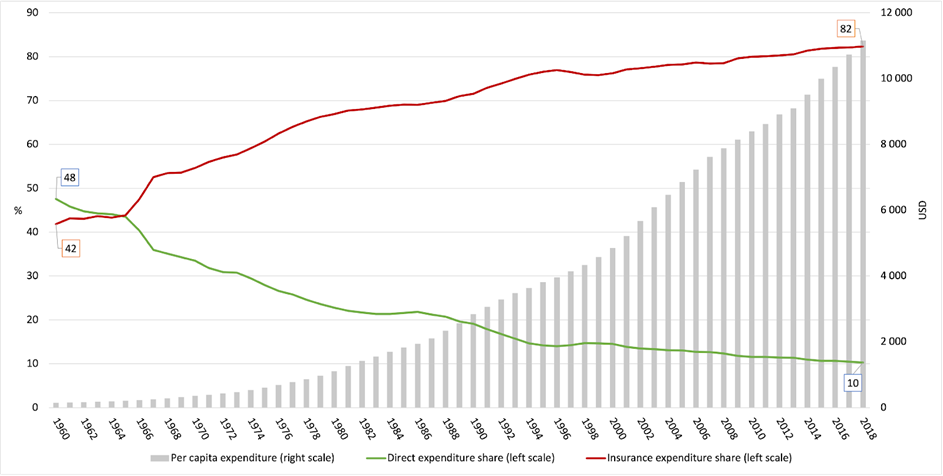

Under market conditions, the lack of health insurance does not explicitly mean a lack of access to health care. Government interventionism in the health insurance market has made it difficult for many Americans to imagine that many medical services can be paid for out of pocket and not go bankrupt. The share of direct payments in the US in 2021 was 11 percent (in 1960 it was 48 percent). However, it is worth noting that this figure includes insurance-related payments: deductible, copayment, and coinsurance. Meanwhile, direct payments without insurance are extremely important, allowing the consumer to pay for the medical services in question without intermediaries. This results in many positive effects like increasing supply and competition among providers.

Economist Thomas Sowell once said: “Making us pay is one way to make us think.” A good example to confirm his words is the cosmetic surgery market. As it turns out, this market does not suffer from supply constraints or high rates of price increases that exceed the inflation rate. Interesting observations are provided by Mark J. Perry of the American Enterprise Institute, who analyzed a 2016 report published by the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Perry pointed out several important facts that testify well to the ability of the unfettered market to provide consumers with needed goods and services:

- Between 1998 and 2016, the average price increase for the 20 most popular cosmetic surgery procedures was 32 percent.

- While prices for medical care services increased by 100.5 percent during this period, prices of hospital services by as much as 176.6 percent, and the consumer price index (CPI) by 47.2 percent.

- The number of all 20 procedures increased from 2,104,674 in 1998 to 8,588,625 in 2016.

- In the case of the 10 most popular treatments in 2016, none of them increased their price since 1998 by more than 47.2 percent.

Economists Goodman, Musgrave, and Herrick, in their book (p.138), pointed to several reasons for this:

One reason is patient behavior. When patients pay with their own money, they have an incentive to be savvy consumers. A second reason is supply. As more people demanded the procedures, more surgeons began to provide them…. A third reason is efficiency. Many providers have operating facilities located in their offices, a less expensive alternative to outpatient surgery at a hospital.... A fourth reason is the emergence of substitute products.

Another example is the private hospital Surgery Center of Oklahoma (SCO). During my research grant at the Mises Institute (March-June 2025), I had the pleasure of interviewing one of its founders, Dr. Keith Smith.

Dr. Smith did not want to bring his facility in to handle government programs or rely on partnerships with private insurers, as he understood too well the institutional drawbacks of such arrangements. Instead, he relied on the unprecedented solution of offering medical services only through direct payment. It might have seemed that such a business model did not stand a chance against insurers’ offerings. However, reality proved Dr. Smith right, as his ideas made the medical benefits offered better rather than worse. The first major change was showing prices for selected medical benefits. Through this simple change, consumers gained information about specific services and their prices. Significantly, in its entire history (since 1997), the SCO has increased prices by about 12 percent only once (in 2021).

This brought great results, as SCO patients gained access to hospital treatments several times cheaper than in “standard” hospitals. A quick Google Gemini query, for example, shows how much it is possible to lower prices for such services while maintaining a certain threshold for business profitability:

- A hip replacement at the SCO might cost $15,500, while a Boston hospital might charge $74,000 for the same procedure.

- A two-level disc decompression surgery might cost $8,500 at the SCO, while another hospital might quote $60,000.

Another interesting story involves a patient from the state of Georgia who was quoted $40,000 by one hospital there for a urologic procedure, and that was the price for the hospitalization alone. In comparison, the total cost at SCO was $4,000. At the time, one of the doctors at that hospital forced the management to reduce the cost, as this was another case where they were losing the patient. In such a situation, the hospital from the state of Georgia “suddenly” lowered the price to $4,000. Later, the patient himself joked that thanks to SCO he saved $36,000 without even using their services.

These positive effects can be stifled when relying primarily on regulated health insurance. This leads to an artificial increase in spending.

Figure 1. Change in the share of individual types of healthcare expenditure (in percent) in total expenditure and per capita expenditure. Source: Own study based on: CMS.

Medical Subscriptions

The solution between insurance and direct payments can be medical subscriptions, which are also better known as Direct Primary Care (DPC). Patients pay fixed monthly fees for the ability to use medical services. Patients are also not charged additional out-of-pocket costs as with health insurance. For doctors, getting enough patients means stable income and the ability to maintain this type of business. Thus, DPC complements the offer of retail clinic networks, which also employ nurses and physician assistants. Doctors providing their services under DPC can devote more time and attention to their patients, which increases trust and contributes to rebuilding the doctor-patient relationship. The average time to visit a doctor under DPC is 30-60 minutes, compared to 15-20 minutes for visits under the insurance model.

A good example of the effectiveness of such efforts is the recent changes in Montana (2021) known as Direct Patient Care. This model offers a wide range of services that support people with chronic illnesses. One of the institutions supporting these changes was the Frontier Institute. Quite recently I had the pleasure of talking a bit about this topic with their CEO—Kendall Cotton. Kendall stated that the changes are having a positive effect:

- Frontier Institute has verified at least 32 healthcare providers located in Montana who operate primarily with the DPC model.

- Healthcare providers using the DPC model in Montana include physicians, nurse practitioners, naturopaths, and pharmacists.

- The average DPC membership fee for comprehensive primary care for an adult is $87/month in Montana.

- Based on the average patient panel size for a DPC provider, Montana’s DPC industry is now providing an estimated 12,000 Montana patients with affordable, high-quality healthcare.

Conclusion

The key elements of a market-based health system outlined are a prescription for government interventionism leading to artificially stimulating demand and artificially reducing the supply of medical services. Market-based solutions do not exclude the needy, but are more diversified ways to ensure their access to health care. The absence of monopoly privileges and deregulation of providers results in an overall increase in accessibility.