[Excerpt from Murray Rothbard, The Progressive Era, Patrick Newman, ed. (Auburn, Ala.: Mises Institute, 2017), from chap. 13 “World War I as Fulfillment: Power and the Intellectuals,” pp. 428–36.]

World War I was the apotheosis of the growing notion of intellectuals as servants of the State and junior partners in State rule. In the new fusion of intellectuals and State, each was of powerful aid to the other. Intellectuals could serve the State by apologizing for and supplying rationales for its deeds. Intellectuals were also needed to staff important positions as planners and controllers of the society and economy. The State could also serve intellectuals by restricting entry into, and thereby raising the income and the prestige of, the various occupations and professions. During World War I, historians were of particular importance in supplying the government with war propaganda, convincing the public of the unique evil of Germans throughout history and of the satanic designs of the Kaiser. Economists, particularly empirical economists and statisticians, were of great importance in the planning and control of the nation’s wartime economy. Historians playing preeminent roles in the war propaganda machine have been studied fairly extensively; economists and statisticians, playing a less blatant and allegedly “value-free” role, have received far less attention.59

Although it is an outworn generalization to say that nineteenth century economists were stalwart champions of laissez faire, it is still true that deductive economic theory proved to be a mighty bulwark against government intervention. For, basically, economic theory showed the harmony and order inherent in the free market, as well as the counterproductive distortions and economic shackles imposed by state intervention. In order for statism to dominate the economics profession, then, it was important to discredit deductive theory. One of the most important ways of doing so was to advance the notion that, to be “genuinely scientific,” economics had to eschew generalization and deductive laws and simply engage in empirical inquiry into the facts of history and historical institutions, hoping that somehow laws would eventually arise from these detailed investigations.

Thus the German Historical School, which managed to seize control of the economics discipline in Germany, fiercely proclaimed not only its devotion to statism and government control, but also its opposition to the “abstract” deductive laws of political economy. This was the first major group within the economics profession to champion what Ludwig von Mises was later to call “anti-economics.” Gustav Schmoller, the leader of the Historical School, proudly declared that his and his colleagues’ major task at the University of Berlin was to form “the intellectual bodyguard of the House of Hohenzollern.”

During the 1880s and 1890s bright young graduate students in history and the social sciences went to Germany, the home of the PhD degree, to obtain their doctorates. Almost to a man, they returned to the United States to teach in colleges and in the newly created graduate schools, imbued with the excitement of the “new” economics and political science. It was a “new” social science that lauded the German and Bismarckian development of a powerful welfare-warfare State, a State seemingly above all social classes, that fused the nation into an integrated and allegedly harmonious whole. The new society and polity was to be run by a powerful central government, cartelizing, dictating, arbitrating, and controlling, thereby eliminating competitive laissez-faire capitalism on the one hand and the threat of proletarian socialism on the other. And at or near the head of the new dispensation was to be the new breed of intellectuals, technocrats, and planners, directing, staffing, propagandizing, and “selflessly” promoting the common good while ruling and lording over the rest of society. In short, doing well by doing good. To the new breed of progressive and statist intellectuals in America, this was a heady vision indeed.

Richard T. Ely, virtually the founder of this new breed, was the leading progressive economist and also the teacher of most of the others. As an ardent postmillennialist pietist, Ely was convinced that he was serving God and Christ as well. Like so many pietists, Ely was born (in 1854) of solid Yankee and old Puritan stock, again in the midst of the fanatical Burned-Over District of western New York. Ely’s father, Ezra, was an extreme Sabbatarian, preventing his family from playing games or reading books on Sunday, and so ardent a prohibitionist that, even though an impoverished, marginal farmer, he refused to grow barley, a crop uniquely suitable to his soil, because it would have been used to make that monstrously sinful product, beer.60 Having been graduated from Columbia College in 1876, Ely went to Germany and received his PhD from Heidelberg in 1879. In several decades of teaching at Johns Hopkins and then at Wisconsin, the energetic and empire-building Ely became enormously influential in American thought and politics. At Johns Hopkins he turned out a gallery of influential students and statist disciples in all fields of the social sciences as well as economics. These disciples were headed by the pro-union institutionalist economist John R. Commons, and included the social-control sociologists Edward Alsworth Ross and Albion W. Small; John H. Finlay, President of City College of New York; Dr. Albert Shaw, editor of the Review of Reviews and influential adviser and theoretician to Theodore Roosevelt; the municipal reformer Frederick C. Howe; and the historians Frederick Jackson Turner and J. Franklin Jameson. Newton D. Baker was trained by Ely at Hopkins, and Woodrow Wilson was also his student there, although there is no direct evidence of intellectual influence.

In the mid-1880s Richard Ely founded the American Economic Association in a conscious attempt to commit the economics profession to statism as against the older laissez-faire economists grouped in the Political Economy Club. Ely continued as secretary-treasurer of the AEA for seven years, until his reformer allies decided to weaken the association’s commitment to statism in order to induce the laissez-faire economists to join the organization. At that point, Ely, in high dudgeon, left the AEA.

At Wisconsin in 1892, Ely formed a new School of Economics, Political Science, and History, surrounded himself with former students, and gave birth to the Wisconsin Idea which, with the help of John Commons, succeeded in passing a host of progressive measures for government regulation in Wisconsin. Ely and the others formed an unofficial but powerful brain trust for the progressive regime of Wisconsin Governor Robert M. La Follette, who got his start in Wisconsin politics as an advocate of prohibition. Though never a classroom student of Ely’s, La Follette always referred to Ely as his teacher and as the molder of the Wisconsin Idea. And Theodore Roosevelt once declared that Ely “first introduced me to radicalism in economics and then made me sane in my radicalism.”61

Ely was also one of the most prominent postmillennialist intellectuals of the era. He fervently believed that the State is God’s chosen instrument for reforming and Christianizing the social order so that eventually Jesus would arrive and put an end to history. The State, declared Ely, “is religious in its essence,” and, furthermore, “God works through the State in carrying out His purposes more universally than through any other institution.” The task of the church is to guide the State and utilize it in these needed reforms.62

An inveterate activist and organizer, Ely was prominent in the evangelical Chautauqua movement, and he founded there the “Christian Sociology” summer school, which infused the influential Chautauqua operation with the concepts and the personnel of the Social Gospel movement. Ely was a friend and close associate of Social Gospel leaders Revs. Washington Gladden, Walter Rauschenbusch, and Josiah Strong. With Strong and Commons, Ely organized the Institute of Christian Sociology.63 Ely also founded and became the secretary of the Christian Social Union of the Episcopal Church, along with Christian Socialist W.D.P. Bliss. All of these activities were infused with postmillennial statism. Thus, the Institute of Christian Sociology was pledged to present God’s “kingdom as the complete ideal of human society to be realized on earth.” Moreover,

Ely viewed the state as the greatest redemptive force in society. In Ely’s eyes, government was the God-given instrument through which we had to work. Its preeminence as a divine instrument was based on the post-Reformation abolition of the division between the sacred and the secular and on the State’s power to implement ethical solutions to public problems. The same identification of sacred and secular which took place among liberal clergy enabled Ely to both divinize the state and socialize Christianity: he thought of government as God’s main instrument of redemption….64

When war came, Richard Ely was for some reason (perhaps because he was in his sixties) left out of the excitement of war work and economic planning in Washington. He bitterly regretted that “I have not had a more active part then I have had in this greatest war in the world’s history.”65 But Ely made up for his lack as best he could; virtually from the start of the European war, he whooped it up for militarism, war, the “discipline” of conscription, and the suppression of dissent and “disloyalty” at home. A lifelong militarist, Ely had tried to volunteer for war service in the Spanish-American War, had called for the suppression of the Philippine insurrection, and was particularly eager for conscription and for forced labor for “loafers” during World War I. By 1915 Ely was agitating for immediate compulsory military service, and the following year he joined the ardently pro-war and heavily big business–influenced National Security League, where he called for the liberation of the German people from “autocracy.”66

In advocating conscription, Ely was neatly able to combine moral, economic, and prohibitionist arguments for the draft: “The moral effect of taking boys off street corners and out of saloons and drilling them is excellent, and the economic effects are likewise beneficial.”67 Indeed, conscription for Ely served almost as a panacea for all ills. So enthusiastic was he about the World War I experience that Ely again prescribed his favorite cure-all to alleviate the 1929 depression. He proposed a permanent peacetime “industrial army” engaged in public works and manned by conscripting youth for strenuous physical labor. This conscription would instill into America’s youth the essential “military ideals of hardihood and discipline,” a discipline once provided by life on the farm but unavailable to the bulk of the populace now growing up in the effete cities. This small, standing conscript army could then speedily absorb the unemployed during depressions. Under the command of “an economic general staff,” the industrial army would “go to work to relieve distress with all the vigor and resources of brain and brawn that we employed in the World War.”68

Deprived of a position in Washington, Ely made the stamping out of “disloyalty” at home his major contribution to the war effort. He called for the total suspension of academic freedom for the duration. Any professor, he declared, who stated “opinions which hinder us in this awful struggle” should be “fired” if not indeed “shot.” The particular focus of Ely’s formidable energy was a zealous campaign to try to get his old ally in Wisconsin politics, Robert M. La Follette, expelled from the US Senate for continuing to oppose America’s participation in the war. Ely declared that his “blood boils” at La Follette’s “treason” and attacks on war profiteering. Throwing himself into the battle, Ely founded and became president of the Madison chapter of the Wisconsin Loyalty Legion and mounted a campaign to expel La Follette.69 The campaign was meant to mobilize the Wisconsin faculty and to support the ultrapatriotic and ultrahawkish activities of Theodore Roosevelt. Ely wrote to TR that “we must crush La Follettism.” In his unremitting campaign against the Wisconsin Senator, Ely thundered that La Follette “has been of more help to the Kaiser than a quarter of a million troops.”70 “Empiricism” rampant.

The faculty of the University of Wisconsin was stung by charges throughout the state and the country that its failure to denounce La Follette was proof that the university — long affiliated with La Follette in state politics — supported his disloyal antiwar policies. Prodded by Ely, Commons, and others, the university’s War Committee drew up and circulated a petition, signed by the university president, all the deans, and over 90 percent of the faculty, that provided one of the more striking examples in United States history of academic truckling to the State apparatus. None too subtly using the constitutional verbiage for treason, the petition protested “against those utterances and actions of Senator La Follette which have given aid and comfort to Germany and her allies in the present war; we deplore his failure loyally to support the government in the prosecution of the war.”71

Behind the scenes, Ely tried his best to mobilize America’s historians against La Follette, to demonstrate that he had given aid and comfort to the enemy. Ely was able to enlist the services of the National Board of Historical Service, the propaganda agency established by professional historians for the duration of the war, and of the government’s own propaganda arm, the Committee on Public Information. Warning that the effort must remain secret, Ely mobilized historians under the aegis of these organizations to research German and Austrian newspapers and journals to try to build a record of La Follette’s alleged influence, “indicating the encouragement he has given Germany.” The historian E. Merton Coulter revealed the objective spirit animating these researches: “I understand it is to be an unbiased and candid account of the Senator’s [La Follette’s] course and its effect — but we all know it can lead but to one conclusion — something little short of treason.”71

Professor Gruber well notes that this campaign to get La Follette was “a remarkable example of the uses of scholarship for espionage. It was a far cry from the disinterested search for truth for a group of professors to mobilize a secret research campaign to find ammunition to destroy the political career of a United States senator who did not share their view of the war.”72 In any event, no evidence was turned up, the movement failed, and the Wisconsin professoriat began to move away in distrust from the Loyalty Legion.73

After the menace of the Kaiser had been extirpated, the Armistice found Professor Ely, along with his compatriots in the National Security League, ready to segue into the next round of patriotic repression. During Ely’s anti–La Follette research campaign he had urged investigation of “the kind of influence which he [La Follette] has exerted against our country in Russia.” Ely pointed out that modem “democracy” requires a “high degree of conformity” and that therefore the “most serious menace” of Bolshevism, which Ely depicted as “social disease germs,” must be fought “with repressive measures.”

By 1924, however, Richard T. Ely’s career of repression was over, and what is more, in a rare instance of the workings of poetic justice, he was hoisted with his own petard. In 1922 the much-traduced Robert La Follette was reelected to the Senate and also swept the Progressives back into power in the state of Wisconsin. By 1924 the Progressives had gained control of the Board of Regents, and they moved to cut off the water of their former academic ally and empire-builder. Ely then felt it prudent to move out of Wisconsin together with his Institute, and while he lingered for some years at Northwestern, the heyday of Ely’s fame and fortune was over.

- 59For a refreshingly acidulous portrayal of the actions of the historians in World War I, see C. Hartley Grattan, “The Historians Cut Loose,” American Mercury, August 1927, reprinted in Haw Elmer Barnes, In Quest of Truth and Justice, 2nd ed. (Colorado Springs: Ralph Myles Publisher, 1972), pp. 142–164. A more extended account is George T. Blakey, Historians on the Homefront: American Propagandists for the Great War (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1970). Gruber, Mars and Minerva, deals with academia and social scientism, but concentrates an historians. James R. Mock and Cedric Larson, Words that Won the War (Princeton University Press, 1939), presents the story of the “Creel Committee,” the Committee on Public Information, the official propaganda ministry during the war.

- 60See the useful biography of Ely, Benjamin G. Rader, The Academic Mind and Reform: The Influence of Richard T. Ely in American Life (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1966).

- 61Sidney Fine, Laissez Faire and the General-Welfare State: A Study of Conflict in American Thought 1865–1901 (Ann Arbor: Univenity of Michigan Press, 1956), pp.239–240.

- 62Fine, Laissez Faire, pp. 180–181.

- 63John Rogers Commons was of old Yankee stock, descendant of John Rogers, Puritan martyr in England, and born in the Yankee area of the Western Reserve in Ohio and reared in Indiana. His Vermont mother was a graduate of the hotbed of pietism, Oberlin College, and she sent John to Oberlin in the hopes that he would become a minister. While in college, Commons and his mother launched a prohibitionist publication at the request of the Anti-Saloon League. After graduation, Commons went to Johns Hopkins to study under Ely, but flunked out of graduate school. See John R. Commons, Myself (Madison, Wisc.: University of Wisconsin Press, 1964). Also see Joseph Dorfman, The Economic Mind in American Civilization (New York: Viking, 1949), vol. 3. 276–277; Mary O. Furner, Advocacy and Objectivity: A Crisis in the Professionalization of American Social Science, 1865–1905 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1975), pp. 198–204.

- 64Quandt, “Religion and Social Thought,” pp. 402–403. Ely did not expect the millennial Kingdom to be far off. He believed that it was the task of the universities and of the social sciences “to teach the complexities of the Christian duty of brotherhood in order to arrive at the New Jerusalem “which we are all eagerly awaiting.” The church’s mission was to attack every evil institution, “until the earth becomes a new earth, and all its cities, cities of God.”

- 65Gruber, Mars and Minerva, p. 114.

- 66See Rader, Academic Mind, pp. 181–191. On top big business affiliations of National Security League leaders, especially J.P. Morgan and others in the Morgan ambit, see C. Hartley Grattan, Why We Fought (New York Vanguard Press, 1929) pp. 117–118, and Robert D. Ward, “The Origin and Activities of the National Security League, 1914–1919,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 47 (June 1960): 51–65.

- 67The Chamber of Commerce of the United States spelled out the long-run economic benefit of conscription, that for America’s youth it would “substitute a period of helpful discipline for a period of demoralizing freedom from restraint.” John Patrick Finnegan, Against the Specter of Dragon: The Campaign for American Military Preparedness, 1914–1917 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1974), p. 110. On the broad and enthusiastic support given to the draft by the Chamber of Commerce, see Chase C. Mooney and Martha E. Layman, “Some Phases of the Compulsory Military Training Movement, 1914–1920,” Mississippi Historical Review 38 (March 1952): 640.

- 68Richard T. Ely, Hard Times: The Way in and the Way Out (1931), cited in Joseph Dorfman, The Economic Mind in American Civilization (New Yark: Viking, 1949). vol. 5, p. 671; and in Leuchtenburg, “The New Deal,” p. 94.

- 69Ely drew up a super-patriotic pledge for the Madison chapter of the Loyalty Legion, pledging its members to “stamp out disloyalty.” The pledge also expressed unqualified support for the Espionage Act and vowed to “work against La Follettism in all its anti-war forms.” Rader, Academic Mind, pp. 183ff.

- 70Gruber, Mars and Minerva, p. 207.

- 71Ibid., p. 207.

- 71Ibid., pp. 208n.

- 72Ibid., pp. 209–210. In his autobiography, written in 1938, Richard Ely rewrote history to cover up his ignominious role in the get–La Follette campaign. He acknowledged signing the faculty petition, but then had the temerity to claim that he “was not one of the ring-leaders, as La Follette thought, in circulating this petition….” There is no mention of his secret research campaign against La Follette.

- 73For more an the anti-La Follette campaign, see H.C. Peterson and Gilbert C. Fite, Opponents of War: 1917–1918 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1957), pp. 68–72; Paul L. Murphy, World War I and the Origin of Civil Liberties in the United States (New York: W.W. Norton, 1979), p. 120; and Belle Case La Follette and Fola La Follette, Robert M. LaFollette (New York: Macmillan, 1953), volume 2.

No content found

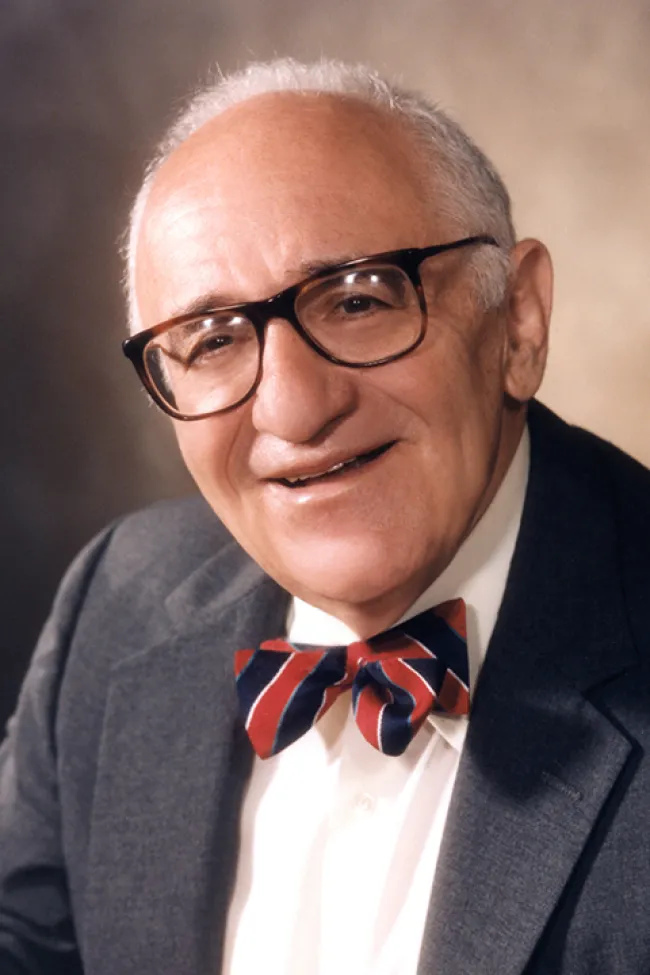

Murray N. Rothbard made major contributions to economics, history, political philosophy, and legal theory. He combined Austrian economics with a fervent commitment to individual liberty.

Into the heart of the peasant and nomadic Arab world of the Middle East there came, on the backs and on the bayonets of British imperialism, a largely European colonizing people.

Are we emphasizing “the negative”? In a sense, yes, but what else are we to stress when our values, our principles, our very being are under attack from a relentless foe?

The Bill of Rights transformed the Constitution from one of supreme and total national power to a partially mixed polity where the liberal anti-nationalists at least had a fighting chance.