I don’t think most Steve Martin fans understand what he has done, but I do. I want to share with you what I regard as the highest-risk career strategy that I have ever seen. It worked. I find it hard to believe, but it worked.

I am not a big fan of Steve Martin’s brand of comedy. I just don’t get it. It is not that I have not given him a chance to win me over. I have. But, after 45 years, I still don’t get it.

I first saw him perform at the Golden Bear, what in those days was called a folk music club. It was in Huntington Beach in Orange County, California. That was back in 1967.

I remember him very well — amazingly well. His performance was that memorable. I had gone to see a friend perform, Steve Gillette. His album had just been released by Vanguard. His song, Back on the Street Again, had been a big hit for the Sunshine Company that year. He was building a following in the region. He was the headliner. Martin was the filler.

Martin stood in front of the crowd with a banjo strapped around his neck. I kept waiting for him to play the banjo. He kept talking. I initially thought he was a banjo player who was filling time by trying to be funny. After about ten minutes, I finally figured out that he was a comedian in training who was using a banjo as a prop. The banjo was his ticket to get on stage in a folk music club.

He picked the banjo a little. Not many people can do a solo banjo act. Peter Seeger could. I can’t think of anyone else.

Martin also pulled out some balloons. He blew them up and made some balloon figures. It was like attending a third-grade birthday party with a clown who was not wearing make-up or funny shoes.

I watched him march up the fame ladder, beginning in the mid-1970s.

What I did not perceive in 1967 was that he was self-consciously trying to create a new kind of comedy: comedy with no punch lines. He developed this into a fine art. Wikipedia describes his transformation, when he was in college.

Martin recalls wondering in a psychology class “What if there were no punch lines? What if there were no indicators? What if I created tension and never released it? What if I headed for a climax, but all I delivered was an anticlimax? What would the audience do with all that tension? Theoretically, it would have to come out sometime. But if I kept denying them the formality of a punch line, the audience would eventually pick their own place to laugh, essentially out of desperation.”

I never did get desperate, so it didn’t work for me. My problem is that I prefer comedy with punch lines, or at least wry humor. I even appreciate satire. But I remain a sucker for a punch line.

I liked his sight gags. I at least understood the balloons. I thought All of Me was funny, because he used his ability to do rubber-body sight gags. Also, it helped that he was teamed up with Lilly Tomlin, who is very funny. His appearance on Johnny Carson’s final show as “The Great Flydini” was creative. But it was basically a series of sight gags with a peculiar twist. His cameo in “Little Shop of Horrors” was clever, because he played a sadistic singing dentist. I got it. Dirty Rotten Scoundrels was amusing because Michael Caine is a great straight man (and great anything else). But I had trouble getting the jokes in Bowfinger. I had the same problem with The Jerk and Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid.

I became a believer only about two years ago. I finally got it. Steve Martin’s entire career was a build-up for the most memorable punch line in the history of stand-up comedy.

For over 40 years, he practiced playing his banjo in private. Then, without warning, he came clean. He has finally started touring with his music. He no longer tries to make us laugh. And let me tell you, he is really good on the banjo. I would pay to hear him play. I just hope he doesn’t add much patter in between songs. A little is OK — about as much as his banjo playing in 1967.

No one would pay to hear him play the banjo if he had not become famous with his comedy. He used comedy as a career marketing tool. It took 45 years, but it worked.

He was never a comedian using a banjo as a prop. He was a banjo player using comedy as a prop. He just needed time to perfect his banjo skills.

We have all heard about actors who wait on tables for years while they work in actors’ studio in the hope of getting a big break in the movies. Martin worked in the movies for years in order to get a big break playing banjo. “Gotcha!”

I get it! The joke’s on me!

I regard this as a long-term career marketing strategy like no other. It deserves to be a case study at the Harvard Business School.

On Being Really Good

Cal Newport recently earned a Ph.D. in computer science from M.I.T. He is famous these days because of his website, which explores the crucial issue of finding your life’s work. His new book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You, is based on an interview of Martin by Charlie Rose. This is from Newport’s site.

“Nobody ever takes note of [my advice], because it’s not the answer they wanted to hear,” Martin said. “What they want to hear is ‘Here’s how you get an agent, here’s how you write a script,’ . . . but I always say, ‘Be so good they can’t ignore you.’”

In response to Rose’s trademark ambiguous grunt, Martin defended his advice: “If somebody’s thinking, ‘How can I be really good?’ people are going to come to you.”

This is exactly the philosophy that catapulted Martin into stardom. He was only twenty years old when he decided to innovate his act into something too good to be ignored. “Comedy at the time was all setup and punch line . . . the clichéd nightclub comedian, rat-a-tat-tat,” Martin explained to Rose. He thought it could be something more sophisticated. It took Martin, by his own estimation, ten years for his new act to cohere, but when it did, he became a monster success. It’s clear in his telling that there was no real shortcut to his eventual fame, and the compelling life it generated. “[Eventually] you are so experienced [that] there’s a confidence that comes out,” Martin explained. “I think it’s something the audience smells.”

I had two problems with Martin’s humor back in 1967. First, I was seeing him perform in the early stage of his career. Second, I just did not get it. Within a decade, a generation of comedy lovers got it, once he had perfected his act. For example, they found the arrow through the head routine incredibly funny. Rose introduced his interview with a clip. Then he added the Czech guys skit, and the King Tut song and dance routine.

Today, 35 years later, I still do not get it. But I get this: Newport’s summary of Martin’s strategy.

If you’re not focusing on becoming so good they can’t ignore you, you’re going to be left behind. This clarity is refreshing. It tells you to stop worrying about what your job offers you, and instead worry about what you’re offering the world. This mindset — which I call the craftsman mindset — allows you to sidestep the anxious questions generated by the passion hypothesis — “Who am I?”, “What do I truly love?” — and instead put your head down and focus on becoming valuable.

Job, Calling, and Career

Newport’s book reports on the work of University of Michigan professor Amy Wrzesniewski. She has studied the careers of numerous highly successful people. In 1997, she published a paper on the three-fold aspects of success in our work: the job factor, the career factor, and the calling factor.

The job puts food on your table. Your career is what you do to advance yourself through life. Your calling is an important part of your life and basically defines you.

I had made a similar observation off the top of my head back in 1981. I focused on job and calling. I did not mention career. I defined calling as “the most important thing you can do in which you would be most difficult to replace.” (I gave a speech to undergraduates on this topic at the summer program of the Mises Institute, Mises University, in August.)

In Wrzesniewski’s sense, a career is that most fundamental skill which you apply to both your job and calling. In my case, it is the skill of writing. I apply it to almost everything I do. This has been true ever since the age of 13. I also developed public speaking skills in high school, and I have continued to speak publicly several times a year, but not until now have I had a real need to implement this skill. Producing videos for Sunday School use and home school use is about to change this in my calling. YouTube has not exactly revolutionized how the world learns, for the world of formal education has always relied on stories and lectures. But the visual impact of videos has moved learning beyond traditional classroom teaching. YouTube has also lowered the price of teaching and learning: a true revolution.

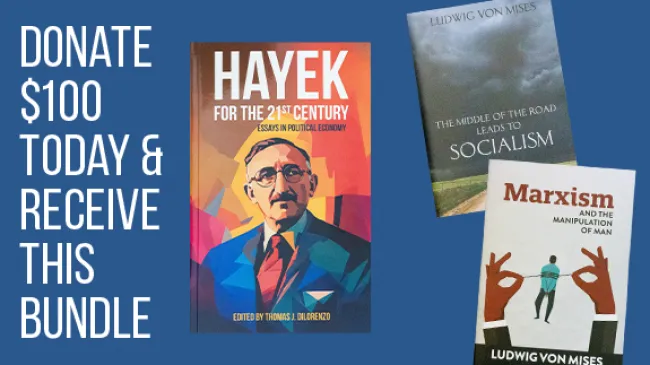

Austrian School Economics

The triumph of Keynesian economics institutionally was secured by a simple fact: Keynes and his followers provided what appeared to be scientific evidence justifying the policies of fiscal deficits and central bank inflation that governments around the world began adopting in the half decade before Keynes’ “General Theory” was published. The governments never reversed these policies, and Keynesianism is still given credence.

There was always demand for court prophets in the theocratic kingdoms of the ancient world. That demand still exists. The formulas today are now mathematical, but they remain formulas. Their goal is to overcome the negative fallout of the spells cast by previous magicians’ formulas.

In the years from 1945 to 1974, when Hayek won the Nobel Prize, Austrian School economics had much the same social function as the prophets’ ministries in the Old Testament. On the fringes of society, a handful of men proclaimed the ancient truths: “Thou shalt not steal.” “Thou shalt not covet.” They refused to tell the people that it is possible to turn stones to bread. They were not given a hearing.

In those years, the foundations of Austrian School economics were laid by Ludwig von Mises, and to a lesser extent, Murray Rothbard. If Mises was Moses, then Rothbard was Joshua. When you read Human Action, you realize how good it is. It is clear. It is written in English. It is comprehensive as no previous treatise had been.

Then read Man, Economy, and State. The writing is almost unequaled in clarity. It is systematic. It is cogent. It is easier to read than “Human Action,” but no less scholarly.

Mises worked in obscurity at New York University until he retired at age 88 in 1969. He awarded four Ph.D degrees from 1945 to 1969. The university did not pay him a salary. The funds were donated. Rothbard labored in even greater obscurity at Brooklyn Polytechnic University, which did not even offer an economics major. He taught engineers.

Rothbard’s career skill was writing. There has been no economist with a wider range of topics on which he has written. His job skill was teaching, and at the end of his career, he did get an endowed chair at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas. This was a school more famous for basketball than scholarship. But he always put food on the table.

His calling was to extend the insights of Mises, not only in economics proper, but also in ancillary fields, especially in the area of political history and its economic roots. But he was widely read in numerous fields. He was no monocausational historian. He regarded the quest for power through coercion as far more comprehensive and a far more irresistible temptation than the mere accumulation of wealth.

Slowly, the Austrian School’s analysis is emerging from the shadows. The prophets of limited civil government are still laboring in the wilderness, but the Internet allows those in the cities to access the message.

The message is the same as it was in the days of Isaiah. It was a series of warnings to rulers. Stop perverting justice (Isaiah 1:21). Stop inflating the currency (Isaiah 1:22). Get ready for judgment (Isaiah 1:24).

Conclusion

Steve Martin did an end run around his fans. He abandoned his banjo when he got more laughs without it. But he never stopped practicing. Now he is back in action, Scruggs style. He made money with his job, but his career in the five-string still is going strong. I don’t think he is any funnier today than he was in 1967, but he is a far better banjo picker.

The careers of Mises, Rothbard, Hazlitt, and their disciples indicate that the attention to detail pays off. They never stopped writing. They never stopped developing insights and applications of their theory of economic causation. They stuck to their knitting.

Today, the literature of Austrian economics is vast compared to 1973, let alone 1945. The ideas are spreading. With every economic crisis, with every fiscal deficit, with every QE, with every kick of the political can, the market for Austrian economics grows.