Character forges destiny, yes; but, if to a lesser degree, so does chance.

For example, in February 1950, I looked for a course to fit into my Monday night schedule at the NYU Graduate School of Business Administration. I, a greenish assistant professor of history and economics at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn bent on getting a PhD--the union card of higher education--hit on something in the school catalogue entitled “Interventionism and the Profit System.”

The course was given by a visiting professor, a certain Ludwig von Mises--a name, I confess, I had never heard of--nor, for that matter, was I attuned to the unintended perverse consequences of government hampering of an otherwise free market or “interventionism,” a word he explained at the first session and one he helped make a part of the economic vocabulary. Anyway, as you see, I registered for the course.

So while convenience (read chance) may have overtaken my marginal interest--I was naive enough in 1948 to campaign a bit for arch-interventionist Chester Bowles, a famed World War II wage and price controller running for the governorship of Connecticut--that Mises course somehow came to charge me more and more to remove mental cobwebs, rethink my thinking--and, frankly, redirect my life.

Indeed, the rethinking around the close of the course began to sweep over me like a tidal wave as one by one my economic theories from a major in NYU undergraduate economics were shaken and ultimately rejected in our vast new untried if popular New Deal depression-born Welfare State.

I suspect my initial hesitation on Misesean thinking reflects the perception of an early 20th century thinker, G. K. Chesterton, who said of the topsy-turvy world of popular opinion: “It isn’t that they can’t see the solution. It is that they can’t see the problem.” Or it reflects a similar thought of Gertrude Stein on her deathbed in Paris in 1946 when she asked her companion Alice B. Toklas, “Well, what is the answer?” Alice shrugged. Gertrude nodded and pressed on, “In that case, what is the question?”

Thus did Dr. Mises shake my thinking by asking, quietly, pointed question after pointed question in his lectures and readings on our then and now shaky intellectual status quo on epistemology or the theory and limits of human knowledge, or on what he called “praxeology,” on what he saw as the science of conscious or purposeful human action.

Human action? As he told the class, each such action undergoes three stages: Unease: the individual feels uneasy, unsettled, dissatisfied--a feeling prodding action--say, drowsiness inducing sleep. Perception: seeing just what action can ease the unease or get more satisfaction/less dissatisfaction; thus does life’s endless search for gain drive action. And, substitution: the action of choosing or trading off a lesser state of affairs for a presumed better state: pursuing happiness or gain as in a contract for marriage or buying a home or investing in a stock. Indeed, so man chooses in each conscious action: action good or bad, sublime or ridiculous. So the rule of an uncertain future and not uncommon misapprehension virtually guarantee human errors, more so in the coercive public than in the voluntary private realm. Or so I came to learn in that Mises course.

Too, Dr. Mises told us of subjectivism, of how mainstream economics embraces empiricism and so much ignores the vast and crucial economy of the mind--of how choices, values, and attitudes set the fate of the individual, the family, the firm, the state, or of organizations, societies, nations, even civilization itself, as witness the death of the Egyptian, Greek, and Roman civilizations. Or as Professor Mises portrayed the collapse of Rome, a victim of sustained interventionism, a lesson for our own interventionistic age, writing in Human Action (1949, p. 763):

“The marvelous civilization of antiquity perished because it did not adjust its moral code and its legal system to the requirements of the market economy. A social order is doomed if the actions which its normal functioning require are rejected by the standards of morality, are declared to be illegal by the laws of the country, and are prosecuted as criminal by the courts and the police. The Roman Empire crumbled to dust because it lacked the spirit of liberalism and free enterprise. The policy of interventionism and its political corollary, the Fuhrer principle, decomposed the mighty empire as they will by necessity always disintegrate and destroy any social entity.”

And so Dr. Mises, in lectures and print, in that spring term more than a half-century ago, challenged conventional wisdom on poverty and wealth, on war and peace, on public vs. private property, on political vs. economic democracy, on “methodological individualism” as he held human action proceeds strictly through individuals even though everyone is a member of various organizations such as families, societies, nationalities, political parties, religious groups, states, etc. Too, Professor Mises saw subjectivism as the key to value, that value is not built or costed into the goods and services themselves but arises only in the minds of market participants. How commonsensical I said later to myself.

Too, he delved into current events, mostly in class Q and A, when he gave us insights to the New Deal, the United Nations, the Marshall Plan, the Cold War as Euro-communism enshrouded Central and Eastern Europe, the Korean War, and so on, as his answers ran sharply if calmly and often wittily against mainstream politics and Keynesian economics.

For example, with democracy the buzz-word of political discourse then and now, I was struck to see how Professor Mises lit up a near-unknown yet highly effective daily democracy--the marketplace--in class and in his Socialism (1922, 1951 ed., p. 21), so giving this democracy a critically needed political dimension. As Dr. Mises wrote: “When we call a capitalist society a consumers’ democracy we mean that the power to dispose of the means of production, which belongs to the entrepreneurs and capitalists, can only be acquired by means of the consumers’ ballot, held daily in the marketplace.”

I ask: Well, isn’t the marketplace then an endless plebiscite, a government of the people, for the people, by the people, exercising their consumer sovereignty over the producers, the entrepreneurs? Or as Dr. Mises cleverly put it in Human Action (1949, p. 270):

“The direction of all economic affairs is in the market society a task of the entrepreneurs. Theirs is the control of production. They are at the helm and steer the ship. A superficial observer would believe that they are supreme. But they are not. They are bound to obey unconditionally the captain’s orders. The captain is the consumer. Neither the entrepreneurs nor the farmers nor the capitalists determine what has to be produced. The consumers do that. If a businessman does not strictly obey the orders of the public as they are conveyed to him by the structure of market prices, he suffers losses, he goes bankrupt, and is thus removed from his eminent position at the helm. Other men who did better in satisfying the demand of the consumers replace him.”

But why all this at a night school? I soon sensed that Dr. Mises--though a scholar of world renown, the author of a journal article in 1920 and Socialism who foresaw the ultimate breakdown of socialism a la the USSR for its lack of “economic calculation” (though he didn’t live to see it)--was a nonconformist, a persona non grata in polite academic circles, as I learned that prestigious American universities quietly backed away from a chair for such a distinguished refugee European scholar. Murray Rothbard, his brilliant American student, gave three reasons for the slur: 1. Ludwig Mises was born a Jew and anti-Semitism was still a problem. 2. He was too committed to laissez faire, an antiquated notion. And: 3. He simply refused to compromise—how unscholarly of him.

So Monday evenings that spring term made for a heady experience. As was signing up in the fall term for the famed Mises seminar, one drawing stars like Murray Rothbard, Israel Kirzner, Hans Sennholz, George Reisman, Sylvester Petro, and Henry Hazlitt. The seminar lasted until 1969 when he retired at the age of 89, probably the oldest active professor in the U.S. Note, by the way, how this New York seminar compares with Mises’s famous Vienna Privatseminar which attracted luminaries like F. A. Hayek, Fritz Machlup, Gottfried Haberler, Felix Kaufmann, Oscar Morgenstern, and Erich Voegelin.

Anyway, so came my rethinking of mainstream economics and aligning myself with Austrian economics and libertarianism. Readings helped prod the conversion, mainly the Mises major opus, Human Action, published by the Yale University Press. What a book! It connects human advancement with human freedom. It demonstrates how free social and pricing coordination via a market society spells social cooperation and peaceful progress. As Henry Hazlitt wrote in Newsweek on September 19, 1949:

“I know of no other work ... which conveys to the reader so clear an insight into the intimate interconnectedness of all economic phenomena. It makes us recognize why it is impossible to study or understand ‘collective bargaining’ or ‘labor problems’ in isolation; or to understand wages apart from prices or from interest rates or from profits and losses, or to understand any of these apart from all the rest, or the price of any of one thing apart from the prices of other things .... Human Action is, in short, at once the most uncompromising and the most rigorously reasoned statement of the case for capitalism that has yet appeared.”

And my rethinking was sharpened all the more by Professor Mises himself. He was an impressive figure if of diminutive height. He always arrived in class on time, well groomed, white-haired, with a trim mustache, soft smile, cultured voice with a slight German accent. His NYU graduate students, for the most part, seemed won over by his European charm, courtliness, his intellectual stature of learning and experience--by, above all, how he put deductive logic, values and history on the side of the free individual.

At nearly every class was his lovely wife, Margit Mises. In 1976 she published My Years with Ludwig von Mises (Mises died in 1973). Here she tells of their early years in Vienna, their dangerous flight from Nazi Europe, the hard first years in America, the dramatic story behind Human Action, that famous long-running NYU seminar, and the last years. She appended two tributes in her book (p. 199 ff.).

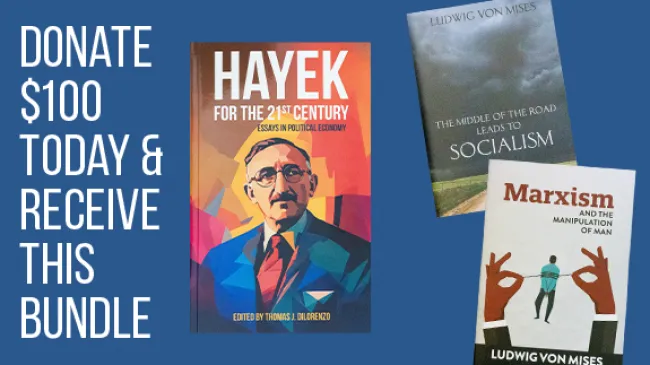

The first tribute was to F. A. Hayek and given to him at a banquet in Chicago in 1962 in Hayek’s honor, a touching one by Ludwig Mises. He hailed Hayek for his 1944 work, The Road to Serfdom, the slim volume that became a bestseller and translated into every civilized language, and for his 1960 work, The Constitution of Liberty, which Mises called “a monumental treatise.” Professor Mises also hailed Hayek for his initiative in 1947 in the founding of the Mont Pelerin Society, with Dr. Mises among some 38 founders. MPS still goes strong, with some 450 members today, and with three of its founders--Hayek, Milton Friedman, and George Stigler--collecting Nobel Prizes in economics.

The second accolade reads: “Tribute to Ludwig von Mises by F. A. von Hayek Given at a Party in Honor of Mises, New York, March 7, 1956.” The event celebrated the publication of On Freedom and Free Enterprise: Essays in Honor of Ludwig von Mises edited by Mary Sennholz (Van Nostrand, 1956, FEE, 1994), and also the 50th anniversary of the University of Vienna’s conferral of a doctorate in law on Ludwig Mises in 1906. Said Friedrich Hayek before asking us to raise our glasses in honor of Dr. Mises:

“I cannot help smiling when I hear Professor Mises described as a conservative. Indeed, in this country and at this time, his views may appeal to people of conservative minds. But when he began advocating them, there was no conservative group which he could support. There couldn’t have been anything more revolutionary, more radical, than his appeal for reliance on freedom. To me, Professor Mises is and remains, above all, a great radical, an intelligent and rational radical but, nonetheless, a radical on the right lines.”

Also at every class was Bettina Bien, a resident scholar at FEE, where Mises also served as a distinguished scholar. Bettina became a highly respected scholar on Mises in America with, for example, her Mises: An Annotated Bibliography (FEE, 1993). At NYU Bettina served as a sort of assistant to Professor Mises. She also became Bettina Bien Greaves on marrying Percy L. Greaves, Jr., who graduated magna cum laude from Syracuse University in 1929, was head of the minority staff of the Joint Congressional Pearl Harbor Investigation, and later the Armstrong professor of economics, with Professor Mises, at the University of Plano in Texas.

Dr. Mises was 69 when I entered his class that February in 1950. I did not know then that Mises in a sense was to have lived two lives: A New York one and a Viennese one when he defended the best of European civilization before and after World War I, including the interwar war during the rise of Naziism which overtook Austria in 1938. Professor Mises had already sensed the Nazi danger and accepted in 1934 the invitation of William Rappard and Paul Mantoux of the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva to assume the Institute’s chair for international economic relations. His six years at the Institute made for a rich teaching and writing period climaxed by his completing Nationalokonomie, the forerunner of Human Action, in 1940.

Meanwhile, Hitler--who blithely split Poland with Stalin with his “blitzkreig” or lightning war in September 1939--ended World War II’s “Phony War” phase when he invaded Norway and Denmark in April 1940, the Netherlands in May 1940, then swept around France’s “impregnable” Maginot Line to blitz Belgium and then France itself, taking Paris in June 1940, and signing an armistice agreement between Germany and Vichy France in the very same railroad car in which Germany signed--it felt ignominiously--the armistice agreement of 1918 ending World War I.

Ludwig and Margit Mises were alarmed as the Nazis, with the help of Axis power Italy to the south, had surrounded Switzerland, with Nazi agents active in Geneva, the site of the defunct League of Nations, and as their Panzer divisions fanned out into the length and breath of France. Mises scrambled for visas from France, Spain, Portugal, and the U.S. for himself and Margit. The two bravely fled Geneva by bus on July 4, 1940 (fittingly America’s Independence Day) for the Spanish border and ultimately America via Lisbon.

As Dr. Mises wrote in his Notes and Recollections (l940, 1978, p. 138): “I left the Institute [and Switzerland] because I could no longer face living in a country that considered my presence a political liability and a danger to its security.” The bus trip was dangerous. As Margit Mises said in her memoir (p. 57): “The German troops had advanced very far, and they were everywhere. More than once our driver had to backtrack to escape them.” Yet they managed to cross the Spanish border and, after an Atlantic crossing that took nine days, reach New York in August 1940. So their American or second life began.

The early American years were tough. 1940 was a low point in Dr. Mises’s morale. He was appalled at how policy-makers of domestic and foreign affairs in America and Europe escalated the very programs that climaxed in a prolonged depression and two world wars. As he wrote In Notes and Recollections (1940, 1976, p. 115):

“Occasionally I entertained the hope that my writings would bear practical fruit and show the way for policy. Constantly I have been searching for evidence of a change in ideology. But I have never allowed myself to be deceived. I have come to realize that my theories explain the degeneration of a great civilization; they do not prevent it. I set out to be a reformer, but only became the historian of decline.”

In her memoir (p. 63), Margit Mises noted how they had to move five times in New York City in their first year. As she wrote: “Lu’s spirits were at a low point during this time. Very often he would say to me: ‘If it were not for you, I would not want to live any more.’ He missed his work, his books, and his income .... Now, here in New York, we had to live from Lu’s savings, and to see his money dwindle .... “

A word on how my turning point on the Mises philosophy swayed my own writing and teaching in the ensuing years: At NYU’s Graduate School of Business Administration, I became associate professor and then professor of economics, later becoming the John David Campbell professor of American business at the American Graduate School of International Management in Arizona, the Scott L. Probasco Jr. professor of free enterprise at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, and the Burrows T. and Mabel L. Lundy professor of business philosophy at Campbell University in North Carolina.

In 1981 the Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge honored me with the Leavey award for excellence in private enterprise education and in 1990 with its George Washington medal of honor. In 1991 the Universidad Francisco Marroquin (I recall its library building entrance emblazoned as the “Ludwig von Mises Library”) in Guatemala awarded me an honorary degree, and in 1993 Campbell University presented me with the Dean’s Award for excellence in teaching. Would these awards have come without my discovery of Misesean thinking? The question begs the answer.

The answer also helps explain why in 1982 I was sponsored by the U.S. Information Agency to lecture on economics in Rumania, East Germany, Ireland, and Canada in which I expressed the futility of the “Third Way,” or why I got out a few books (e.g., The Great Farm Problem, Regnery,1959) and why my articles have appeared in The Freeman: Ideas on Liberty, Harvard Business Review, Washington Times, Free Market, Challenge, Christian Science Monitor, New York Times, Business Week, Investors Business Daily, Journal of Business, Journal of Economic Literature, Nihon Keizai Shimbun (Tokyo), Farmand (Oslo), Australian (Sydney), Sunday Times (London), and for 14 years a regular column, “Reading for Business,” in the Wall Street Journal.

Piece de resistance was Mary and I being invited into “the Mises Family” of Margit and Lu Mises, Bertha and Larry Fertig, Frances and Harry Hazlitt, Elena and Phil Cortney, Agnes and Len Read, Helen and Syl Petro, and others. Memories galore. Good parties, good conversations, good laughs, and commiserations on the fate of politics-ever-fracturing mankind. All in all, quite a trip; I wouldn’t have missed it for the world.

So I agree with Israel Kirzner’s tribute of Lu Mises as “the free-market economist of the 20th century” in Kirzner’s Ludwig von Mises: The Man and His Economics (ISI Books, 2001, p. 163) , and how (p. 196) “the broad sweep of Mises’ view of the workings of the market economy--his focus on human action, on the purposefulness of action, on the entrepreneurial element in the market process, on the subjectivism with which economic understanding must be pursued--will continue to find a place within the menu of intellectual options available in 21st century economic thought.” Let’s hope so.

Yet there is one more thing for me to credit Ludwig von Mises: a role model for each of us--whoever you are--for his standing up to the power elite of mainstream politics and economics, for valor in the face of all manner of fire, for never giving up. And to do so with verve and wit. For example, here’s a gem from the Margit Mises memoir (1984 ed., p. 181) when Mises, in his 90’s, told her: “The only good thing about being a nonogenarian is that you are able to read your obituaries while you are still alive.” So Terence had a point, saying c. 160 B.C.: Fortes fortuna adjuvat (Fortune favors the brave).

Or, better, as Mises said of himself in his Notes and Recollections (p. 70):

“In high school I had chosen a verse by Virgil as my motto: Tu ne cede malis sed contra audentior ito. (”Do not yield give in to evil, but proceed against it ever more boldly.”) In the darkest hours of the war, I recalled this dictum. Again and again, I faced situations from which rational deliberations could find no escape. But then something unexpected occurred that brought deliverance. I would not lose courage even now. I would do everything an economist could do. I would not tire in professing what I knew to be right.”