“By the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes.” - Shakespeare, Macbeth

Humphrey Neill’s little gem of a book, The Art of Contrary Thinking, was groundbreaking in at least one respect. Published in 1954, it gave the English-speaking world a new word, at least according to the lexicographers of the Oxford English Dictionary. Neill’s dedication in this book is the oldest citation of the word contrarian. “To Contrarians and Libertarians everywhere,” Neill declared, “May there numbers grow”!

Neill then went on to develop his idea of contrarian thinking. Contrary thinking certainly has roots older than 1954, but perhaps never before had any writer so carefully and explicitly dealt with the subject as Neill did.

In any event, the theory of contrarianism advises that you ”Thrust your thoughts out of a rut. In a word, be a nonconformist when using your mind.” Or, to use another oft-quoted Neillism, “When everyone thinks alike, everyone is likely to be wrong.”

It is after thinking about Neill’s pithy nuggets of wisdom that one can’t but help feel a sense of unease about the consensus views on the risks of inflation. Inflation, in the sense used here, is the popular one used to describe a phenomenon of generally rising prices, or stated in another way, a decline in the purchasing power of the dollar. Though that definition is less than ideal, it is widely used. For the moment, a concession to popular prejudice is made to focus on the point at hand. The primary point is to warn, as does an old Malay proverb, that just because the river is quiet does not mean the crocodiles have left.

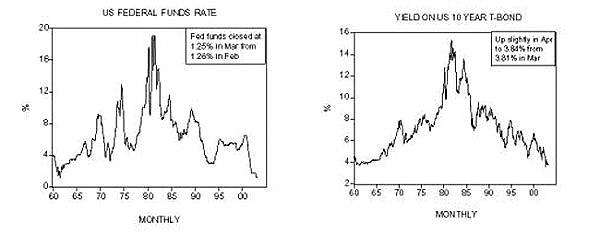

Interest rates, as all homeowners can attest, are very low when viewed against a longer historical backdrop. It is a commonly served dish of economic commentary that home mortgage refinancing and the housing market generally have helped sustain the economy despite recent weakness in many other lines of business. Across the spectrum, rates are low. The ten-year Treasuries are priced to yield around 4%. Earlier in the year, the yield on that instrument touched a 45-year low – a miniscule 3.56% – a yield not seen since the summer of 1958. Those who bear the monetary scars inflicted by the destructive powers of 20th century inflation surely had to rub their eyes in disbelief.

These veterans know that the bond market’s reputation for absolute safety is undeserved. After all, there are plenty of instances in history where bond investors were fleeced. Investors lent money to the US government to finance World War II at rates of 2.5% for terms of between ten and twenty years in length. By doing so, they committed themselves to a 2.5% return on their money on the eve of a massive period of inflation. Those investors who held these bonds for the duration suffered major losses as inflation ate away at their savings.

Apparently, the message today from the bond market is that inflation is not a worry. The purchasing power of the dollar is secure enough, bondholders seem to say, that it is okay to tie your money up for ten-years at 4%.

So too, on an anecdotal level, inflation worries are simply nowhere to be found in the nation’s leading newspapers. Inflation worries have elusively slipped off-stage, like an aging diva that has been pushed from the limelight by a younger and sexier performer.

War and terrorism are the new glamour girls of news that dominate the headlines, deservedly so, it might be said. Even if they did not, there are a host of other concerns likely to get top billing before inflationary worries these days. Among them, the budget crises of most state and local governments, for example, or the spiraling cost of health care.

Yet, there are clues and warnings, beyond mere contrarian instincts, that inflation will once again have her day.

James Grant, in Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, expresses concerns about the price tag of the war with Iraq, recently estimated by the administration at $74 billion, sans occupation and re-building costs. The monetary cost of the war is anybody’s guess and true to the nature of guesses, they range over a wide field. In addition to the cost of the war itself, Grant notes the accommodating role the Federal Reserve Bank historically plays in supporting the expenditures of the national government. The two together–spiraling war and post-war expenses, and the easy credit of the Fed–possess sufficient power to stir the inflationary pot, in Grant’s view.

Summarizing the action of the bond markets, Grant’s writes “The new consensus of opinion in the bond market holds…[that] heavy public borrowing, fast-paced debt monetization, and high commodity prices are non-inflationary. We had somehow believed the opposite.” The juxtaposition of these conflicting things has not gone completely unnoticed. Bill Gross, too, has written about them in his past letters to shareholders.

Bill Gross, the reigning bond guru and manager of the world’s largest bond fund, wrote in his latest letter to shareholders that “the salad days are over” by which he meant that with rates as low as they are, bondholders could no longer expect the returns of the past. He warns, “should reflationary efforts take hold, price protection will be the order of tomorrow.”

Then there is the message from the commodity pits. The DJ-AIB Commodities Futures index, depicted in the Wall Street Journal everyday, is up 16% from a year ago. Gold, oil, natural gas, and other natural resources have been rising. International turmoil may explain some of these increases, but the movements are broad enough for some to conclude that something more propels these commodities.

Outstanding Investments, a newsletter dedicated to following the natural resource market, wrote in its March issue that the commodity price increases represented “the latest manifestation of an inflationary environment.” Here in the commodity pits, at least, there would seem to be some clue that the purchasing power of the dollar may not be as secure as bondholders hope.

Beyond this, there is perhaps the most powerful reason of all – fiat currency is simply no good. Theory and history agree that its value only diminishes over time. It’s primary weakness is what Fed governors think is its greatest strength. The printing press analogy has been used not only by critics of fiat currency, but also by Federal Reserve Board governor Ben Bernanke, who in a November 21 speech said that the government can “produce as many U.S. dollars as it wishes at essentially no cost.” Yet another shot across the bow for those who still believe inflation is dead.

Some writers are always on guard against inflation, realizing that it is the nature of the beast that is fiat currency. S. Allen Nathanson, a corporate executive and life-long student of finance, wrote a series of wide-ranging essays appearing mainly in the years 1966-1973. These letters have been collected and re-published recently under the title Bullishly Speaking.

One persistent thought expressed in the book is the author’s never-dying fear of inflation. He wrote, “The more I study the more I consistently return to the same conclusion. The entire world is imbibing from the same bottle, the bottle of inflation–each country’s hangover consists of a currency that is shrinking in value similar to a cube of ice that slowly melts in a glass of water.”

In another passage, Nathanson wrote, “Inflation is an American way of life. It may hesitate but never stop. Perhaps in our lifetime it may only creep, but there is always a possibility that it will start to gallop.” There is some irony in the fact that Nathanson wrote during a time when there was still some semblance of a gold standard still in place, though he correctly predicted its demise even in his early essays.

It seems that in post-bubble America, at the dawning years of the 21st century, people have forgotten that this horse still has legs and the barn door is wide open and unattended.

Inflation is a process that forcefully re-distributes wealth from one group to another. Prices do not change uniformly in this process, and those that get the new dollars before their costs have risen gain at the expense of those whose costs rise first.

Austrian economics has long taught that analysis of inflation must proceed sequentially as it courses through the economic system. Moreover, it is this inflationary process that sets the cycle of boom and bust in motion. Prices are distorted and investments are inevitably made in unsustainable lines, leading ultimately to a liquidation, or bust, revealing the precious capital that had been wasted.

The only way to stop such a process is to separate money and government. Free-market money mean money backed by something other than the decree of government promising to replace paper with paper.

It is for the reasons outlined here that the fate of the dollar and with it, the savings of millions of Americans, is less than bright. Our future standard of living depends on our ability to return to a sound currency. For hundreds of years, gold was good enough. Let’s hope that it will be again.