When asked about price inflation in his Sunday interview with 60 Minutes, President Joe Biden claimed that inflation "was up just an inch … hardly at all." Biden continued the dishonest tactic of focusing on month-to-month price inflation growth to obscure forty-year highs in year-over-year inflation. This strategy may yet work to placate the most ignorant voters, but people who are paying attention know that price inflation continues to soar.

Thus, while Biden may be pretending that it's all no big deal, the Federal Reserve knows it better do something about price inflation, which even the Fed now admits shows no signs of even moderating.

Another 75 Basis Points

On Wednesday, the Fed's Federal Open Market Committee announced that it will again raise the federal funds rate by 75 basis points. According to the FOMC's press release:

Inflation remains elevated, reflecting supply and demand imbalances related to the pandemic, higher food and energy prices, and broader price pressures….

The Committee decided to raise the target range for the federal funds rate to 3 to 3-1/4 percent and anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate. In addition, the Committee will continue reducing its holdings of Treasury securities and agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities, as described in the Plans for Reducing the Size of the Federal Reserve's Balance Sheet that were issued in May. The Committee is strongly committed to returning inflation to its 2 percent objective.

This is, by far, the most hawkish announcement out of the Powell Fed yet and no doubt shows that the Fed has finally come to terms with the fact that inflation is not transitory—as the Fed long insisted—and is now impossible to deny. Last month, Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation rose 8.2 percent year over year marking six months of year-over-year price inflation rates over 8 percent and near-forty-year highs.

Moreover, in its summary of economic projections, many FOMC committee members said they expect the target policy rate to reach or exceed 4.25 percent this year and exceed 4.5 percent in 2023. Projections of economic conditions, however, continued to be relatively rosy, with the report suggesting that gross domestic product (GDP) growth will stay above zero for the foreseeable future, while unemployment maxes out at only 5 percent.

In spite of two quarters in a row of shrinking GDP, and in spite of many indicators of brewing recession—such as falling home prices and an inverting yield curve—the committee is still clinging to the idea that the Fed can steer the economy to a "soft landing" in which inflation will be reined in with no more than some moderate slowing in economic growth.

Although the recent hikes in the target fed funds rate suggest an increasingly hawkish position, the Fed nonetheless continues to take only the most tepid steps when it comes to reducing the size of its portfolio. Such a move would directly reduce the money supply by reversing quantitative easing (QE), and it would also reduce asset prices by producing a small deluge of government bonds and mortgage-backed securities flowing back into the market.

While the Fed is allowing some government bonds to continue to roll off the portfolio, we shouldn't expect any drastic moves here. It's been nearly four months since the Fed announced plans to reduce the portfolio, yet the actual reduction continues to be miniscule. Moreover, when asked about selling off the Fed's mortgage-backed securities in a press conference on Wednesday, Powell responded, "It's something I think we will turn to, but that time—the time for turning to it has not come…. It's not close."

Even now, after immense and rapid price inflation over the past two years, the Fed is still too afraid of fragility in the housing market to put much of its $2 trillion MBS portfolio back into the private sector.

This sends a mixed message as to how much the Fed is really committed to reducing price inflation, but it's clear Powell was trying to project a hawkish tone on Wednesday overall.

Powell spoke of "significantly reducing the size of our balance sheet" and also emphasized that ending the current bout of inflation will require pain in the form of job losses. He also emphasized that there is no short-term solution, strongly implying that the current effort to end inflation could possibly take years.

Powell expressed fears that price inflation will become much harder to address once the population comes to expect inflation as routine. He also noted that price inflation in housing "is going to remain high for some time." Powell then reiterated that there is no way to "wish away" inflation, but that the only way the Fed can do something about inflation is by "slow[ing] the economy." (See 1:35:00 here.)

The question remains, however, whether or not the Fed and the federal government can politically tolerate a sizable period of rising interest rates and a decline in the monetary growth rate.

A decline in the monetary growth rate is trouble because it points to recession. Our bubble economy is now so addicted to easy money that even a slowing in monetary expansion can send the economy's many zombie companies into a tailspin. Rising rates are a problem because they can lead to a sizable increase in the federal government's debt-service payments. This could lead to a fiscal crisis without cuts to popular government spending programs. Virtually no one in Washington wants that.

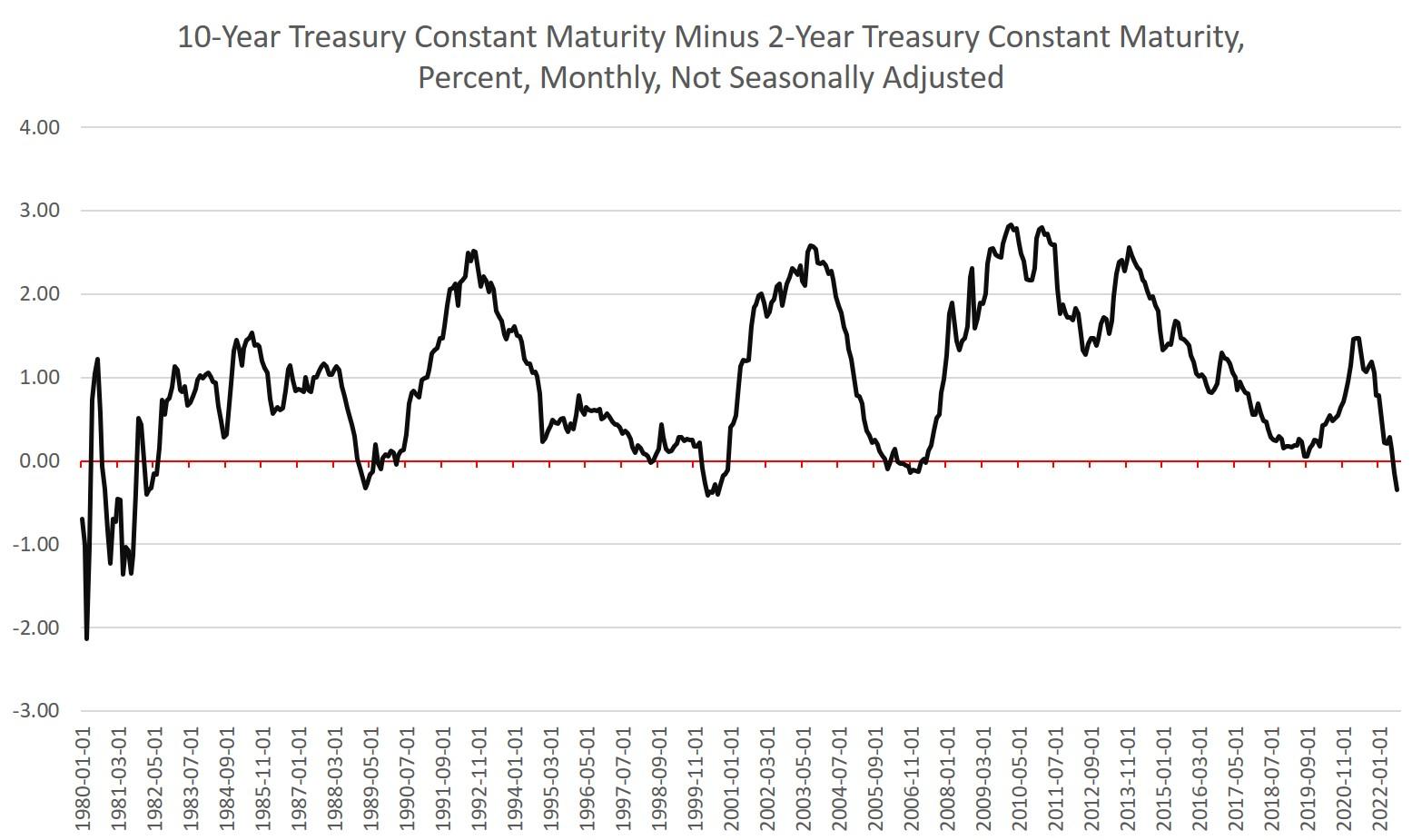

Some key warning signs are already flashing "recession," such as the inverting yield curve. The ten-year yield minus the two-year yield has been negative since July, and at the most negative level since the early 1980s.

This will amount to immense pressure on the Fed—from wealthy Wall Streeters, elected officials, and corners of the economic Left—to return to quantitative easing.

Expect more attacks on the Fed's tightening policy, but most of these attacks will get things backward when it comes to understanding the problem with Fed policy. As even Fed economists are now beginning to understand, the Fed must tighten now or risk truly galloping inflation in the near future. Many casual observers will then view this tightening as the "cause" of the economic pain that will follow.

Yet the Fed's real incompetence is already behind us. That came over the past decade, when the Fed absolutely refused to end its quantitative easing efforts even though the economy was clearly in an accelerating expansion. This was especially obvious after 2017, and yet Powell stuck with the usual monetary inflation, because that was the popular thing to do. Then, when the covid crisis came, all restraints on monetary inflation were completely abandoned.

Now, thanks to Powell's mistakes, price inflation is supercharged, and even he admits it could take years of economic stagnation or decline to bring it under control. The sheer level of ineptitude would be shocking if it were not so common for central bankers. For those people, their entire "strategy" can be summed up—as Peter St. Onge puts it—"hike til it breaks, cut til it inflates." There's not much more to it than that. That's the best all those PhDs at the Fed have managed to come up with. Thanks to Powell and Yellen and Bernanke and Greenspan, we're living with the consequences of the Greenspan Put, followed by a decade of QE, followed by the "panic and print money" mania of the past two years. It's great that Powell is finally figuring out what the real world looks like. Unfortunately he's years behind.