5. The Theory of Monopolistic or Imperfect Competition

5. The Theory of Monopolistic or Imperfect CompetitionA. Monopolistic Competitive Price

A. Monopolistic Competitive PriceThe theory of monopoly price has been generally superseded in the literature by the theories of “monopolistic” or “imperfect” competition.71 As against the older theory, the latter have the advantage of setting up identifiable criteria for their categories—such as a perfectly elastic demand curve for pure competition. Unfortunately, these criteria turn out to be completely fallacious.

Essentially, the chief characteristic of the imperfect-competition theories is that they uphold as their “ideal” the state of “pure competition” rather than “competition” or “free competition.” Pure competition is defined as that state in which the demand curve for each firm in the economy is perfectly elastic, i.e., the demand curve as presented to the firm is completely horizontal. In this supposedly pristine state of affairs, no one firm can, through its actions, possibly have any influence over the price of its product. Its price is then “set” for it by the market. Any amount it produces can and will be sold at this ruling price. In general, it is this state of affairs, or else this state without uncertainty (“perfect competition”), that has received most of the elaborate analysis in recent years. This is true both for those who believe that pure competition fairly well represents the real economy and for their opponents, who consider it only an ideal with which to contrast the actual “monopolistic” state of affairs. Both camps, however, join in upholding pure competition as the ideal system for the general welfare, in contrast to various vague “monopoloid” states that occur when there is departure from the purely competitive world.

The pure-competition theory, however, is an utterly fallacious one. It envisages an absurd state of affairs, never realizable in practice, and far from idyllic if it were. In the first place, there can be no such thing as a firm without influence on its price. The monopolistic-competition theorist contrasts this ideal firm with those firms that have some influence on the determination of price and are therefore in some degree “monopolistic.” Yet it is obvious that the demand curve to a firm cannot be perfectly elastic throughout. At some points, it must dip downward, since the increase in supply will tend to lower market price. As a matter of fact, it is clear from our construction of the demand curve that there can be no stretch of the demand curve, however small, that is horizontal, although there can be small vertical stretches. In aggregating the market demand curve, we saw that for each hypothetical price, the consumers will decide to purchase a certain amount. If the producers attempt to sell a larger amount, they will have to conclude their sale at a lower price in order to attract an increased demand. Even a very small increase in supply will lead to a perhaps very small lowering of price. The individual firm, no matter how small, always has a perceptible influence on the total supply. In an industry of small wheat farms (the implicit model for “pure competition”), each small farm contributes a part of the total supply, and there can be no total without a contribution from each farm. Therefore, each farm has a perceptible, even if very small, influence. No perfectly elastic demand curve can, then, be postulated even in such a case. The error in believing in “perfect elasticity” stems from the use of such mathematical concepts as “second order of smalls,” by which infinite negligibility of steps can be assumed. But economics analyzes real human action, and such real action must always be concerned with discrete, perceptible steps, and never with “infinitely small” steps.

Of course, the demand curve for each small wheat farm is likely to be very highly, almost perfectly, elastic. And yet the fact that it is not “perfect” destroys the entire concept of pure competition. For how does this situation differ from, say, the Hershey Chocolate Company if the demand curve for the latter firm is also elastic? Once it is conceded that all demand curves to firms must be falling, the monopolistic-competition theorist can make no further analytic distinctions.

We cannot compare or classify the curves on the basis of degrees of elasticity, since there is nothing in the Chamberlin-Robinson monopolistic-competition analysis, or in any part of praxeology for that matter, that permits us to do so, once the case of pure competition is rejected. For praxeology cannot establish quantitative laws, only qualitative ones. Indeed, the only recourse of monopolistic-competition theorists would be to fall back on the concepts of “inelastic” vs. “elastic” demand curves, and this would precisely plunge them right back into the old monopoly-price vs. competitive-price dichotomy. They would have to say, with the old monopoly-price theorists, that if the demand curve for the firm is more than unitarily elastic at the equilibrium point, the firm will remain at the “competitive” price; that if the curve is inelastic, it will rise to a monopoly-price position. But, as we have already seen in detail, the monopoly-competitive price dichotomy is untenable.

According to the monopolistic-competition theorists, the two influences sabotaging the possible existence of pure competition are “differentiation of product” and “oligopoly,” or fewness of firms, where one firm influences the actions of others. As to the former, the producers are accused of creating an artificial differentiation among products in the mind of the public, thus carving out for themselves a portion of monopoly. And Chamberlin originally attempted to distinguish “groups” of producers selling “slightly” differentiated products from old-fashioned “industries” of firms making identical products. Neither of these attempts has any validity. If a producer is making a product different from that of another producer, then he is a unique “industry”; there is no rational basis for any grouping of varied producers, particularly in aggregating their demand curves. Furthermore, the consuming public decides on the differentiation of products on its value scales. There is “artificial” about the differentiation, and indeed this differentiation serves to cater more closely to the multifarious wants of the consumers.72 It is clear, of course, that Ford has a monopoly on the sale of Ford cars; but this is a full “monopoly” rather than a “monopolistic” tendency. Also, it is difficult to see what difference can come from the number of firms that are producing the same product, particularly once we discard the myth of pure competition and perfect elasticity. Much ado indeed has been made about strategies, “warfare,” etc., between oligopolists, but there is little point to such discussions. Either the firms are independent and therefore competing, or they are acting jointly and therefore cartelizing. There is no third alternative.

Once the perfect-elasticity myth has been discarded, it becomes clear that all the tedious discussion about the number and size of firms and groups and differentiation, etc., becomes irrelevant. It becomes relevant only for economic history, and not for economic analysis.

It might be objected that there is a substantial problem of oligopoly: that, under oligopoly, each firm has to take into account the reactions of competing firms, whereas under pure competition or differentiated products without oligopoly, each firm can operate in the blissful awareness that no competitor will take account of its actions or change its actions accordingly. Hiram Jones, the small wheat farmer, can set his production policy without wondering what Ezra Smith will do when he discovers what Jones’ policy is. Ford, on the other hand, must consider General Motors’ reactions, and vice versa. Many writers, in fact, have gone so far as to maintain that economics can simply not be applied to these “oligopoly” situations, that these are indeterminate situations where “anything may happen.” They define the buyers’ demand curve that presents itself to the firm as assuming no reaction by competing firms. Then, since “few firms” exist and each firm takes account of the reactions of others, they proceed to the conclusion that in the real world all is chaos, incomprehensible to economic analysis.

These alleged difficulties are nonexistent, however. There is no reason why the demand curve to a firm cannot include expected reactions by other firms.73 The demand curve to a firm is the set of a firm’s expectations, at any time, of how many units of its product consumers will buy at an alternative series of prices. What interests the producer is the hypothetical set of consumer demands at each price. He is not interested in what consumer demand will be in various sets of nonexistent situations. His expectations will be based on his judgment of what would actually happen should he charge various alternative prices. If his rivals will react in a certain way to his charging a higher or a lower price, then it is each firm’s business to forecast and take account of this reaction in so far as it will affect buyers’ demand for its particular product. There would be little sense in ignoring such reactions if they were relevant to the demand for its product or in including them if they were not. A firm’s estimated demand curve, therefore, already includes any expected reactions of rivals.

The relevant consideration is not the fewness of the firms or the state of hostility or friendship existing among firms. Those writers who discuss oligopoly in terms applicable to games of poker or to military warfare are entirely in error. The fundamental business of production is service to the consumers for monetary gain, and not some sort of “game” or “warfare” or any other sort of struggle between producers. In “oligopoly,” where several firms are producing an identical product, there cannot persist any situation in which one firm charges a higher price than another, since there is always a tendency toward the formation of a uniform price for each uniform product. Whenever firm A attempts to sell its product higher or lower than the previously ruling market price, it is attempting to “discover the market,” to find out what the equilibrium market price is, in accordance with the present state of consumer demand. If, at a certain price for the product, consumer demand is in excess of supply, the firms will tend to raise the price, and vice versa if the produced stock is not being sold. In this familiar pathway to equilibrium, all the stock that the firms wish to sell “clears the market” at the highest price that can be obtained. The jockeying and raising and lowering of prices that takes place in “oligopolistic” industries is not some mysterious form of warfare, but the visible process of attempting to find market equilibrium—that price at which the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded will be equal. The same process, indeed, takes place in any market, such as the “nonoligopolistic” wheat or strawberry markets. In the latter markets the process seems to the viewer more “impersonal,” because the actions of any one individual or firm are not as important or as strikingly visible as in the more “oligopolistic” industries. But the process is essentially the same, and we must not be led to think differently by such often inapt metaphors as the “automatic mechanisms of the market” or the “soulless, impersonal forces on the market.” All action on the market is necessarily personal; machines may move, but they do not purposefully act. And, in oligopoly situations, the rivalries, the feelings of one producer toward his competitors, may be historically dramatic, but they are unimportant for economic analysis.

To those who are still tempted to make the number of producers in any field the test of competitive merit, we might ask (setting aside the problem of proving homogeneity): How can the market create sufficient numbers? If Crusoe exchanges fish for Friday’s lumber on their desert island, are they both benefiting, or are they “bilateral monopolists” exploiting each other and charging each other monopoly prices? But if the State is not justified in marching in to arrest Crusoe and/or Friday, how can it be justified in coercing a market where there are obviously many more competitors?

Economic analysis, in conclusion, fails to establish any criterion for separating any elements of the free-market price for a product. Such questions as the number of firms in an industry, the sizes of the firms, the type of product each firm makes, the personalities or motives of the entrepreneurs, the location of plants, etc., are entirely determined by the concrete conditions and data of the particular case. Economic analysis can have nothing to say about them.74

- 71In particular, see Edward H. Chamberlin, Theory of Monopolistic Competition, and Mrs. Joan Robinson, Economics of Imperfect Competition. For a lucid discussion and comparison of the two works, see Robert Triffin, Monopolistic Competition and General Equilibrium Theory (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1940). The differences between the “monopolistic” and the “imperfect” formulations are not important here.

- 72Recently, Professor Chamberlin has conceded this point and has, in a series of remarkable articles, astounded his followers by repudiating the concept of pure competition as a welfare ideal. Chamberlin now declares: “The welfare ideal itself ... is correctly described as one of monopolistic competition. ... [This] seems to follow very directly from the recognition that human beings are individual, diverse in their tastes and desires, and moreover, widely dispersed spatially.” Chamberlin, Towards a More General Theory of Value, pp. 93–94; also ibid., pp. 70–83; E.H. Chamberlin and J.M. Clark, “Discussion,” American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, May, 1950, pp. 102–04; Hunter, “Product Differentiation and Welfare Economics,” pp. 533–52; Hayek, “The Meaning of Competition” in Individualism and the Economic Order, p. 99; and Marshall I. Goldman, “Product Differentiation and Advertising: Some Lessons from Soviet Experience,” Journal of Political Economy, August, 1960, pp. 346–57. See also note 28 above.

- 73This definition of the demand curve to the firm was Mrs. Robinson’s outstanding contribution, unfortunately repudiated by her recently. Triffin castigated Mrs. Robinson for evading the problem of “oligopolistic indeterminacy,” whereas actually she had neatly solved this pseudo problem. See Robinson, Economics of Imperfect Competition, p. 21. For other aspects of oligopoly, see Willard D. Arant, “Competition of the Few Among the Many,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, August, 1956, pp. 327–45.

- 74For an acute criticism of monopolistic-competition theory, see L.M. Lachmann, “Some Notes on Economic Thought, 1933–53,” South African Journal of Economics, March, 1954, pp. 26 ff., especially pp. 30–31. Lachmann points out that economists generally treat types of “perfect” or “monopolistic” competition as static market forms, whereas competition is actually a dynamic process.

B. The Paradox of Excess Capacity

B. The Paradox of Excess CapacityPerhaps the most important conclusion of the theory of monopolistic or imperfect competition is that the real world of monopolistic competition (where the demand curve to each firm is necessarily falling) is inferior to the ideal world of pure competition (where no firm can affect its price). This conclusion was expressed simply and effectively by comparing two final equilibrium states: under conditions of pure and monopolistic competition (Figure 70).

AC is a firm’s average total-cost curve—its alternative dollar costs per unit—with output on the horizontal axis and prices (including costs) on the vertical axis. The only assumption we need in drawing the average-cost curve is that, for any plant in any branch of production, there will be some optimum point of production, i.e., some level of output at which average unit cost is at a minimum. All levels of production lower or higher than the optimum have a higher average cost. In pure competition, where the demand curve for any firm is perfectly elastic, Dp, each firm will eventually adjust so that its AC curve will be tangent to Dp, in equilibrium; in this case, at point E. For if average revenue (price) is greater than average cost, then competition will draw in other firms, until the curves are tangent; if the cost curve is irretrievably higher than demand, the firm will go out of business. Tangency is at point E, price at 0G, and output at 0K. As in any definition of final equilibrium, total costs equal total revenues for each firm, and profits are zero.

Now contrast this picture with that of monopolistic competition. Since the demand curve (Dmf) is now sloping downward to the right, it must, given the same AC curve, be tangent at some point (F), where the price is higher (JF) and the production lower (0J) than under pure competition. In short, monopolistic competition yields higher prices and less production—i.e., a lower standard of living—than pure competition. Furthermore, output will not take place at the point of minimum average cost—clearly a social “optimum,” and each plant will produce at a lower than optimum level, i.e., it will have “excess capacity.” This was the “welfare” case of the monopolistic-competition theorists.

By a process of revision in recent years, some of it by the originators of the doctrine themselves, this theory has been effectively riddled beyond repair. As we have seen, Chamberlin and others have shown that this analysis does not apply if we are to take consumer desire for diversity as a good to be satisfied.75 Many other effective and sound attacks have been made from different directions. One basic argument is that the situations of pure and of monopolistic competition cannot be compared because the AC curves would not, in fact, be the same. Chamberlin has pursued his revisionism in this realm also, declaring that the comparisons are wholly illegitimate, that to apply the concept of pure competition to existing firms would mean, for example, assuming a very large number of similar firms producing the identical product. If this were done, say, with General Motors, it would mean that either GM must conceptually be divided up into numerous fragments, or else that it be multiplied. If divided, then unit costs would undoubtedly be higher, and then the “competitive firm” would suffer higher costs and have to subsist on higher prices. This would clearly injure consumers and the standard of living; thus, Chamberlin follows Schumpeter’s criticism that the “monopolistic” firm may well have and probably will have lower costs than its “purely competitive” counterpart. If, on the other hand, we conceive of the multiplication of a very large number of General Motors corporations at existing size, we cannot possibly relate it to the present world, and the whole comparison becomes absurd.76

In addition, Schumpeter has stressed the superiority of the “monopolistic” firm for innovation and progress, and Clark has shown the inapplicability, in various ways, of this static theory to the dynamic real world. He has recently shown its fallacious asymmetry of argument with respect to price and quality. Hayek and Lachmann have also pointed out the distortion of dynamic reality, as we have indicated above.77

A second major line of attack has shown that the comparisons are much less important than they seem from conventional diagrams, because cost curves are empirically much flatter than they appear in the textbooks. Clark has emphasized that firms deal in long-run considerations, and that long-run cost and demand curves are both more elastic than short-run; hence the differences between E and F points will be negligible and may be nonexistent. Clark and others have stressed the vital importance of potential competition to any would-be reaper of monopoly price, from firms both within and without the industry, and also the competition of substitutes between industries. A further argument has been that the cost curves, empirically, are flat within the relevant range, even aside from the long- vs. short-run problems.78

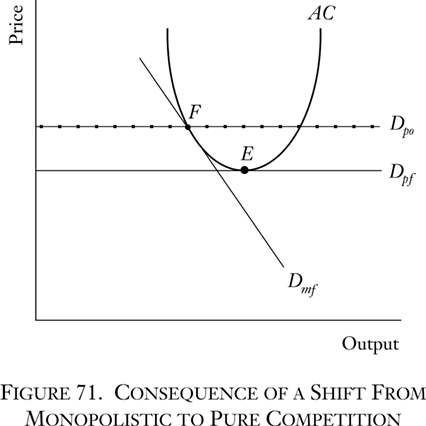

All these arguments, added to our own analysis given above, have effectively demolished the theory of monopolistic competition, and yet more remains to be said. There is something very peculiar about the entire construction, even on its own terms, aside from the fallacious “cost-curve” approach, and practically no one has pointed out these other grave defects in the theory. In an economy that is almost altogether “monopolistically competitive,” how can every firm produce too little and charge too much? What happens to the surplus factors? What are they doing? The failure to raise this question stems from the modern neglect of Austrian general analysis and from undue concentration on an isolated firm or industry.79 The excess factors must go somewhere, and in that case must they not go to other monopolistically competitive firms? In which case, the thesis breaks down as self-contradictory. But the proponents have prepared a way out. They take, first, the case of pure competition, with equilibrium at point E. Then, they assume a sudden shift to conditions of monopolistic competition, with the demand curve for the firm now sloping downward. The demand curve now shifts from Dp to Dmo. Then the firm restricts production and raises its price accordingly, reaps profits, attracts new firms entering the industry, the new competition reduces the output salable by each firm, and the demand curve shifts downward and to the left until it is tangent to the AC curve at point F. Hence, say the monopolistic-competition theorists, not only does monopolistic competition suffer from too little production in each firm and excessive costs and prices; it also suffers from too many firms in each industry. Here is what has happened to the excess factors: they are trapped in too many uneconomic firms.

This seems plausible, until we realize that the whole example has been constructed as a trick. If we isolate a firm or an industry, as does the example, we may just as well start from a position of monopolistic competition, at point F, and then suddenly shift to conditions of pure competition. This is certainly just as legitimate, or rather illegitimate, a base for comparison. What then? As we see in Figure 71, the demand curve for each firm is now shifted from Dmf to Dpo. It will now be profitable for each firm to expand its output, and it will then make profits. New firms will then be attracted into the industry, and the demand curve will fall vertically, until it again reaches tangency with the AC curve at point E. Are we now “proving” that there are more firms in an industry under pure than under monopolistic competition?80 The fundamental error here is failure to see that, under the conditions established by the assumptions, any change opening up profits will bring new firms into an industry. Yet the theorists are supposed to be comparing two different static equilibria, of pure and of monopolistic competition, and not discussing paths from one to the other. Thus, the monopolistic-competition theorists have by no means solved their problem of surplus factors.

But, aside from this point, there are more difficulties in the theory, and Sir Roy Harrod, himself one of its originators, is the only one to have seized the essence of the remaining central difficulty. As Harrod says:

If the entrepreneur foresees the trend of events, which will in due course limit his profitable output to x – y units, why not plan to have a plant that will produce x – y units most cheaply, rather than encumber himself with excess capacity? To plan a plant for producing x units, while knowing that it will only be possible to maintain an output of x – y units, is surely to suffer from schizophrenia.

And yet, asserts Harrod puzzledly, the “accepted doctrine” apparently deems it “impossible to be an entrepreneur and not suffer from schizophrenia!”81 In short, the theory assumes that, in the long run, a firm having to produce at F will yet construct a plant with minimum costs at point E. Clearly, here is a patent contradiction with reality. What is wrong? Harrod’s own answer is an excellent and novel discussion of the difference between long-run and short-run demand curves, with the “long run” always being a factor in entrepreneurial planning, but he does not precisely answer this question.

The paradox becomes “curiouser and curiouser” when we fully realize that it all hinges on a mathematical technicality. The reason why a firm can never produce at an optimum cost point is that (a) it must produce at a tangent of demand and average-cost curves in equilibrium, and (b) if the demand curve is falling, it follows that it can be tangent to a U-shaped cost curve only at some point higher than, and to the left of, the trough point. There are two considerations that we may now add. First, there is no reason why the cost “curve” should, in fact, be curved. In an older day, textbook demand curves used to be curves, and now they are often straight lines; there is even more reason for believing that cost curves are a series of angular lines. It is of course (a) more convenient for diagrams, and (b) essential to mathematical representation, for there to be continuous curves, but we must never let reality be falsified in order to fit the niceties of mathematics. In fact, production is a series of discrete alternatives, as all human action is discrete, and cannot be smoothly continuous, i.e., move in infinitely small steps from one production level to another. But once we recognize the discrete, angular nature of the cost curve, the “problem” of excess capacity immediately disappears (Figure 72). Thus the falling demand curve to the “monopolistic” firm, Dm, can now be “tangent” to the AC curve at E, the minimum-cost point, and will be so in final equilibrium.

There is another way for this pseudo problem to disappear, and that is to call into question the entire assumption of tangency. The tangency of average cost and demand at equilibrium has appeared to follow from the property of equilibrium: that total costs and total revenues of the firm will be equal, since profits as well as losses will be zero. But a key question has been either overlooked or wrongly handled. Why should the firm produce anything, after all, if it earns nothing from doing so? But it will earn something, in equilibrium, and that will be interest return. Modern orthodoxy has fallen into this error, for one reason: because it does not realize that entrepreneurs are also capitalists and that even if, in an evenly rotating economy, the strictly entrepreneurial function were no longer to be required, the capital-advancing function would still be emphatically necessary.

Modern theory also tends to view interest return as a cost to the firm. Naturally, if this is done, then the presence of interest does not change matters. But (and here we refer the reader to foregoing chapters) interest is not a cost to the firm; it is an earning by a firm. The contrary belief rests on a superficial concentration on loan interest and on an unwarranted separation between entrepreneurs and capitalists. Actually, loans are unimportant and are only another legal form of entrepreneurial-capitalist investment. In short, in the evenly rotating economy, the firm earns a “natural” interest return, dictated by social time preference. Hence, Figure 72 must be altered to look like the diagram in Figure 73 (setting aside the problem of curves vs. angles). The firm will produce 0K, its optimum production level, at minimum average cost, KE. Its demand curve and cost curve will not be tangent to each other, but will allow room for equilibrium interest return, represented by the area EFGH. (Neither, as some may object, will the price be higher in this corrected version of monopolistic competition; for this AC curve is lower all around than the previous ones, which had included interest return in costs. If they did not include interest, and instead assumed that interest would be zero in the ERE, then they were wrong, as we have pointed out above.)82 And so the paradox of the monopolistic-competition theory is finally and fully interred.83

- 75And the product differentiation associated with the falling demand curve may well lower costs of distribution and of inspection (as well as improve consumer knowledge) to more than offset the supposed rise in production costs. In short, the AC curve above is really a production-cost, rather than a total-cost, curve, neglecting distribution costs. Cf. Goldman, “Product Differentiation and Advertising.” Furthermore, a genuine total-cost curve would then not be independent of the firm’s demand curve, thus vitiating the usual “cost-curve” analysis. See Dewey, Monopoly in Economics and Law, p. 87. Also see section C below.

- 76See Chamberlin, “Measuring the Degree of Monopoly and Competition” and “Monopolistic Competition Revisited” in Towards a More General Theory of Value, pp. 45–83.

- 77See J.M. Clark, “Competition and the Objectives of Government Policy” in E.H. Chamberlin, ed., Monopoly and Competition and Their Regulation (London: Macmillan & Co., 1954), pp. 317–27; Clark, “Toward a Concept of Workable Competition” in Readings in the Social Control of Industry (Philadelphia: Blakiston, 1942), pp. 452–76; Clark, “Discussion”; Abbott, Quality and Competition, passim; Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democrac (New York: Harper & Bros., 1942); Hayek, “Meaning of Competition”; Lachmann, “Some Notes on Economic Thought, 1933–53.”

- 78See the above citations by Clark; and Richard B. Heflebower, “Toward a Theory of Industrial Markets and Prices” in R.B. Heflebower and G.W. Stocking, eds., Readings on Industrial Organization and Public Policy (Homewood, Ill.: Richard D. Irwin, 1958), pp. 297–315. A more dubious argument—the flatness of the firm’s demand curve in the relevant range—has been stressed by other economists, notably A.J. Nichol, “The Influence of Marginal Buyers on Monopolistic Competition,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, November, 1934, pp. 121–34; Alfred Nicols, “The Rehabilitation of Pure Competition,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, November, 1947, pp. 31–63; and Nutter, “Plateau Demand Curve and Utility Theory.”

- 79But cf. Abbott, Quality and Competition, pp. 180–81.

- 80The author first learned this particular piece of analysis from the classroom lectures of Professor Arthur F. Burns, and, to our knowledge, it has never seen print.

- 81Harrod, Economic Essays, p. 149.

- 82After arriving at this conclusion, the author came across a brilliant but neglected article pointing out that interest is a return and not a cost, and showing the devastating implications of this fact for cost-curve theory. The article does not, however, apply the theory satisfactorily to the problem of monopolistic competition. See Gabor and Pearce, “A New Approach to the Theory of the Firm,” and idem, “The Place of Money Capital.” While there are a few similarities, Professor Dewey’s critique of the “excess capacity” doctrine is essentially very different from ours and based on far more “orthodox” considerations. Dewey, Monopoly and Economics in Law, pp. 96 ff.

- 83Since the erroneous but popular theory of “countervailing power,” propounded by J.K. Galbraith, falls with the monopolistic-competition theory, it is unnecessary to discuss it here. For a more detailed critique of its numerous fallacies, see Simon N. Whitney, “Errors in the Concept of Countervailing Power,” Journal of Business, October, 1953, pp. 238–53; George J. Stigler, “The Economist Plays with Blocs,” American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, May, 1954, pp. 8–14; and David McCord Wright, “Discussion,” ibid., pp. 26–30.

C. Chamberlin and Selling Cost

C. Chamberlin and Selling CostOne of Professor Chamberlin’s most important contributions is alleged to have been his sharp distinction between “selling cost” and “production cost.”84 “Production costs” are supposed to be the legitimate expenses needed to increase supply in order to meet given consumer demand schedules. “Selling costs,” on the other hand, are supposed to be directed toward influencing consumers and increasing their demand schedules for the firm’s product.

This distinction is completely spurious.85 Why does a businessman invest money and incur any costs whatever? To supply a hoped-for demand for his product. Every time he improves his product he is hoping that consumers will respond by increasing their demands. In fact, all costs expended on raw materials are incurred in an attempt to increase consumer demand beyond what it would have been in the absence of these costs. Therefore, every production cost is also a “selling cost.”

Conversely, selling costs are not the sheer waste or even tyranny that monopolistic-competition theorists have usually assumed. The various expenses designated as “selling costs” perform definite services for the public. Basically, they furnish information to the public about the goods of the seller. We live in a world where there can be no “perfect knowledge” of products by anyone—especially consumers, who are faced with a myriad of available products. Selling costs are therefore important in providing information about the product as well as about the firm. In some cases, e.g., displays, the “selling cost” itself directly improves the quality of the product in the mind of the consumer. It must always be remembered that the consumer is not simply buying a physical product; he may also be buying “atmosphere,” prestige, service, etc., all of which have tangible reality to him and are valued accordingly.86

The view that a selling cost is somehow an artifact of “monopolistic competition” stems only from the peculiar assumptions of “pure competition.” In the “ideal” world of pure competition, we remember, each firm’s demand is given to it as infinitely elastic, so that it can sell whatever it wants at the ruling price. Naturally, in such a situation, no selling costs are necessary, because a market for a product is automatically assured. In the real world, however, there is no perfect knowledge, and the demand curves are neither given nor infinitely elastic.87 Therefore, firms have to try to increase demands for their products and to carve out market areas for themselves.

Chamberlin falls into another error in implying that selling costs, such as advertising, “create” consumer demands. This is the determinist fallacy. Every man as a self-owner freely decides his own scale of valuations. On the free market no one can force another to choose his product. And no other individual can ever “create” someone’s values for him; he must adopt the value himself.88

- 84Chamberlin, Theory of Monopolistic Competition, pp. 123ff. Chamberlin includes in selling costs advertising, sales expenses, and store displays.

- 85See Mises, Human Action, p. 319. Also see Kermit Gordon, “Concepts of Competition and Monopoly—Discussion,” American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, May, 1955, pp. 486–87.

- 86It is surely highly artificial to call bright ribbons on a packaged good a “production cost,” while labeling bright ribbons decorating the store selling the good as a “selling cost.”

- 87Cf. Alfred Nicols, “The Development of Monopolistic Competition and the Monopoly Problem,” Review of Economics and Statistics, May, 1949, pp. 118–23.

- 88See Mises:

The consumer is, according to ... legend, simply defenseless against “high-pressure” advertising. If this were true, success or failure in business would depend on the mode of advertising only. However, nobody believes that any kind of advertising would have succeeded in making the candlemakers hold the field against the electric bulb, the horsedrivers against the motorcars. ... But this implies that the quality of the commodity advertised is instrumental in bringing about the success of an advertising campaign. ... The tricks and artifices of advertising are available to the seller of the better product no less than to the seller of the poorer product. But only the former enjoys the advantages derived from the better quality of his product. (Mises, Human Action, pp. 317–18)