9. Production: Particular Factor Prices and Productive Incomes

9. Production: Particular Factor Prices and Productive Incomes1. Introduction

1. IntroductionUP TO THIS POINT WE have analyzed the determination of the rate of interest and of the prices of productive factors on the market. We have also discussed the role of entrepreneurship in the changing world and the consequences of changes in saving and investment. We now return to analysis of the particular ultimate factors—labor and land—and to a more detailed discussion of entrepreneurial incomes. Our analysis of general factor pricing in chapter 7 treated prices as they would be in the ERE, a state toward which they are always tending. Our discussion of entrepreneurship in chapter 8 showed that this tendency is a result of drives toward profits and away from losses by capitalist-entrepreneurs. Now let us return to the particular factors and analyze their pricing, their supplies and incomes, and the effects of a changing economy upon them.

2. Land, Labor, and Rent

2. Land, Labor, and RentA. Rent

A. RentWe have been using the term rent in our analysis to signify the hire price of the services of goods. This price is paid for unit services, as distinguished from the prices of the whole factors yielding the service. Since all goods have unit services, all goods will earn rents, whether they be consumers’ goods or any type of producers’ goods. Future rents of durable goods tend to be capitalized and embodied in their capital value and therefore in the money presently needed to acquire them. As a result, the investors and producers of these goods tend to earn simply an interest return on their investment.

All goods earn gross rent, since all have unit services and prices for them. If a good is “rented out,” it will earn gross rent in the hire charge. If it is bought, then its present price embodies discounted future rents, and in the future it will earn these rents by contributing to production. All goods, therefore, earn gross rents, and here there is no analytic distinction between one factor and another.

Net rents, however, are earned only by labor and land factors, and not by capital goods.1 For the gross rents earned by a capital good will be imputed to gross rents paid to the owners of the factors that produced it. Hence, on net, only labor and land factors—the ultimate factors—earn rents, and, in the ERE, these, along with interest on time, will be the only incomes in the economy.

The Marshallian theory holds that durable capital goods earn “quasirents” temporarily, while permanent lands earn full rents. The fallacy of this theory is clear. Whatever their durability, capital goods receive gross rents just as lands do, whether in the changing real world or the ERE. In the ERE, they receive no net rents at all, since these are imputed to land and labor. In the real world, their capital value changes, but this does not mean that they earn net rents. Rather, these changes are profits or losses accruing to their owners as entrepreneurs. If, then, incomes in the real world are net rents (accruing to labor and land factors) and entrepreneurial profits, while the latter disappear in the ERE, there is no room in either world for the concept of “qua-sirent.” Nowhere does this special type of income exist.

A wage is the term describing the payment for the unit services of a labor factor. A wage, therefore, is a special case of rent; it is labor’s “hire.” On a free market this rent cannot, of course, be capitalized, since the whole labor factor—the man—cannot be bought and sold for a price, his income to accrue to his owner. This is precisely what occurs, however, under a regime of slavery. The wage, in fact, is the only source of rent that cannot be capitalized on the free market, since every man is necessarily a self-owner with an inalienable will.

One distinction between wages and land rents, then, is that the latter are capitalized and transformed into interest return, while the former are not. Another distinction is purely empirical and not apodictically true for mankind. It has simply been an historical-empirical truth that labor factors have always been relatively scarcer than land factors. Land and labor factors can be ranged in order of their marginal value productivity. The result of a relative superfluity of land factors is that not all the land factors will be put to use, i.e., the poorest land factors will be left idle, so that labor will be free to work the most productive land (e.g., the most productive agricultural land, urban sites, fish hatcheries, “natural resources,” etc.). Laborers will tend to use the most value-productive land first, the next most productive second, etc. At any given time, then, there will be some land—the most value-productive—under cultivation and use, and some not in use. The latter, in the ERE, will be free land, since its rental earnings are zero, and therefore its price will be zero.2 The former land will be “supramarginal” and the latter land will be “submarginal.” On the dividing line will be the poorest land now in use; this will be the “marginal” land, and it will be earning close to zero rent.

It is important to recognize the qualification that the marginal land will earn not zero, but only close to zero, rent.3 The reason is that, in human action, there is no infinite continuity, and action cannot proceed in infinitely small steps. Mathematically minded writers tend to think in such terms, so that the points before and after the point under consideration all tend to merge into one. Using marginal land, however, will pay only if it earns some rent, even though a small one. And, in cases where there are large discontinuities in the array of MVPs for different lands, the marginal land might be earning a substantial sum. It is obvious that there is no praxeological precision in terms like “close,” “substantial,” etc. All that we can say with certainty is that if we arrange the MVPs of lands in an array, the rents of the submarginal lands will be zero. We cannot say what the rent of the marginal land will be, except that it will be closer to zero than that of the supramarginal lands.4

Now we have seen above that the marginal value product of a factor decreases as its total supply increases, and increases as the supply declines. The three major categories of factors in the economy are land, labor, and capital goods. In the progressing economy, the supply of capital per person increases.5 The supply of all ranks of capital goods increases, thereby decreasing the marginal value productivities of capital goods, so that the prices of capital goods fall. The relative MVPs of land and labor factors, in the aggregate, tend to rise, so that their income will rise in real terms, if not in monetary ones.

What if the supply of capital remained the same, while the supply of labor or land factors changed? Thus, suppose that, with the same capital structure, population increases, thus expanding the total supply of labor factors. The result will be a general fall in the MVP of labor and a rise in the MVP of land factors. This rise will cause formerly submarginal, no-rent lands to earn rent and to enter into cultivation by the new labor supply. This is the process particularly emphasized by Ricardo: population pressing on the land supply. The tendency for the MVP of labor to drop, however, may well be offset by a rise in the MPP schedules of labor, since a rise in population will permit a greater utilization of the advantages of specialization and the division of labor. The constant supply of capital would have to be reoriented to the changed conditions, but the constant amount of money capital will then be more physically productive. Hence, there will be an offsetting tendency for the MVPs of labor to rise. At any time, for any given conditions of capital and production processes, there will be an “optimum” population level that will maximize the total output of consumers’ goods per head in the economy. A lower level will not take advantage of enough division of labor and opportunities for labor, so that the MPP of labor factors will be lower than at the optimum point; a higher level of population will decrease the MVP of labor and will therefore lower real wages per person.6

Recognition of the existence of a theoretical “optimum” population that maximizes real output per head, given existing land and capital, would go far to end the dreary Malthusian controversies in economic theory. For whether a given increase in population at any time will lead to an increase or decrease in real output per head is an empirical question, depending on the concrete data. It cannot be answered by economic theory.7

It might be wondered how the statement that increasing population might increase MPP and MVPs can be reconciled with the demonstration above that factors will always be put to work in areas of diminishing physical returns. The conditions here are completely different, however. In the previous problem we were assuming a given total supply of the various factors and considering the best method of their relative arrangement. Here we are dealing, not with particular production processes and given supplies of factors, but with the vague concept of “production” in general and with the effect of change in the total supply of a factor. Furthermore, we are dealing not with a true factor (homogeneous in its supply), but with a “class of factors,” such as land-in-general or labor-in-general. Aside from the problem of vagueness, it is evident that the conditions of our present problem are completely different. For if the total supply of a factor changes and it has an effect on the productivity of the labor factor, this is equivalent to a shift in the MPP curves (or schedules) rather than a movement along the curves such as we considered above.8

Because we are accustomed to viewing labor implicitly as scarcer than land factors, we speak in terms of zero-rent land. If the situations were reversed, and lands were scarcer than labor factors, we would have to speak of zero-wage laborers, submar-ginal labor, etc. Theoretically, this is certainly possible, and it might be argued that in such static societies with institutionally limited markets as ancient Sparta and medieval or post-Medieval Europe, this condition actually obtained, so that the “surplus labor” earned a below-subsistence wage in production. Those who were “surplus” and did not own invested capital were curbed by infanticide or reduced to beggary.

That submarginal land earns no rent has given rise to an unfortunate tendency to regard the very concept of rent as a “differential” one—as referring particularly to differences in quality between factors. Sometimes the concept of “absolute” or pure rents is thrown overboard completely, and we hear only of rent in a “differential sense,” as in such statements as the following:

If land A earns 100 gold ounces a month, and land B earns zero, land A is making a differential rent of 100.

If laborer A earns 50 gold ounces a month, and laborer B earns 30 gold ounces, A earns a “rent of ability” of 20 ounces.

On the contrary, rents are absolute and do not depend on the existence of a poorer factor of the same general category. The “differential” basis of rent is purely dependent on, and derived from, absolute rents. It is simply a question of arithmetical subtraction. Thus, land A may earn a rent of 100, and land B a rent of zero. Obviously, the difference between 100 and zero is 100. In the case of the laborer, however, laborer A’s “rent,” i.e., wage, is 50 and B’s is 30. If we want to compare the two earnings, we may say that A earns 20 more than B. There is little point, however, in adding to confusion by using “rent” in this sense.

The “differential rent” concept has also been used to contrast earnings by a factor in one use with those of the same factor in another use. Thus, if a factor, whether land or labor, earns 50 ounces per month in one use and would have earned 40 ounces in some other use, then its “rent” is 10 ounces. Here, “differential rent” is used to mean the difference between the actual DMVP and the opportunity forgone or the DMVP in the next best use. It is sometimes believed that the 10-ounce differential is in some way not “really” a part of costs to entrepreneurs, that it is surplus or even “unearned” rent acquired by the factor. It is generally admitted that it is not without cost to individual firms, which have bid the factor up to its MVP of 50. It is supposed, however, to be without cost from the “industry point of view.” But there is no industry “point of view.” Not “industries,” but firms, buy and sell and seek profits.

In fact, the entire discussion concerning whether or not rent is “costless” or enters into cost is valueless. It belongs to the old classical controversies about whether rents are “price-determined” or “price-determining.” The view that any costs can be price-determining is a product of the old cost-of-production theory of value and prices. We have seen that costs do not determine prices, but vice versa. Or more accurately, prices of consumers’ goods, through market processes, determine the prices of productive factors (ultimately land and labor factors), and the brunt of price changes is borne by specific factors in the various fields.

- 1Net rents equal gross rents earned minus gross rents paid to owners of factors.

- 2Its capital value will be positive, however, if people expect the land to earn rents in the near future.

- 3As Frank Fetter stated in “The Passing of the Old Rent Concept,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, May, 1901:

The last unit of product of any finite amount would ... have to pay its corresponding rent. The only product obtained, in the strict theory of the case, without paying rent, would be one unit infinitesimally small—in plain Anglo-Saxon, would be nothing at all. No finite unit of product can be shown to be a no-rent unit. (p. 489) - 4The terms “marginal,” “supramarginal,” etc., are rather differently used here from the way they are used above. Instead of dealing with the supply and demand for a homogeneous good or factor, we are here referring to one class of factors, such as lands, and comparing different qualities of the various factors in that class. The near-zero-earning land is “marginal” because it is the one just barely put to use.

- 5Here we shift the definition of progressing economy to mean increasing capital per person, so that we can contrast the effects of changes in the supply of one type of factor to changes in the supply of another.

- 6There is, of course, no reason to assume that maximum real income per head is necessarily the best ethical ideal; for some, the ideal might be maximum real income plus maximum population. In a free society, parents are free to choose their own ethical principles in the matter.

- 7Economics can say little else about population and its size. The inclusion of a corpus of “population theory” under economics instead of biology or psychology is the unfortunate result of the historical accident that the early economists were the first to delve into demographic problems.

- 8The Lausanne way (of Walras and Pareto) of phrasing this distinction would be to say that, in the former case (when we are moving along the curve), we implicitly assumed that “(the supply of) tastes, techniques, and resources remains given in the economy.” In the present case, we are considering a change in a resource (e.g., an increase in the supply of labor). We would amend this to say that only tastes and resources were considered given. As we saw in the previous section, techniques are not immediate determinants of production changes. The techniques must be put to use via saving and investment. In fact, we may deal with tastes and resources alone, provided that we include time preferences among the “tastes.”

B. The Nature of Labor

B. The Nature of LaborIn the free society, as we have indicated above, the site could not originally become the property of anyone until it had been “used” in some way, such as being cleared, cultivated, etc. There need be no subsequent use, however, until rents can be obtained.

C. Supply of Land

C. Supply of LandWe have seen throughout that the processes of price determination for the unit services of land and labor are exactly the same. Both sets of factors tend to earn their MVP; both receive advances of present money from capitalist-entrepreneurs; etc. The analysis of the pricing of unit services of original or “permanent” factors applies equally to each. There are three basic differences between the conditions of land and those of labor, however, that make separation of the two important. One we have already dealt with in detail: that (in the free economy) land can be capitalized in its price as a “whole factor” and therefore earns simply interest and entrepreneurial changes in asset value; while labor cannot be capitalized. A second difference we have been considering—the empirical fact that labor has been more scarce than land factors. A corollary of this is that labor is preeminently the nonspecific factor, which is applicable to all processes of production, whereas land tends to be far more specific. A third difference derives from the fact that laborers are human beings and—also an empirical fact—that leisure is always a consumers’ good. As a result, there will be reserve prices for labor against leisure, whereas land—in the broadest sense—will not have a reserve price. We shall deal with the effects of this distinction presently.

The fact that labor is scarcer and nonspecific means that there will always be unused land. Only the best and most productive land will be used, i.e., the land with the highest DMVPs. Similarly, in the real world of uncertainty, where errors are made, there will also be unused capital goods, i.e., in places where malinvestments had been made which turned out to be unprofitable.

We may now trace the supply and demand curves for land factors. We have shown above that, for any factor, the particular demand curve for any use, i.e., the particular MVP curve for a factor in that use, will slope downward in the region in which the factor is working. Also, we have seen that the general demand curve for the factor in the range of all its uses will slope downward. What of the supply curves for land factors? If we take the general supply curve (the factor considered in relation to all of its uses), then it is clear that there is no reservation demand curve for land; at least this will be true in the ERE. The particular supply curves for each use will depend on the alternate uses a piece of land may have. If it has any alternative uses, its supply curve for each use will slope upward as its price increases, since it can be shifted from one use to another as a use yields a higher rental return.

In its particular uses, the landowner will have a reservation demand, since he may obtain a higher return by shifting to another use. The greater the extent of alternate uses, the flatter each particular supply curve will tend to be.

In Figure 62, the left-hand diagram depicts the supply and demand curves for the general use of a land factor, including all uses. The supply curve will be the stock—a vertical straight line. The right-hand diagram below depicts typical demand and supply curves for a particular use; here, the supply curve slopes upward because it can shift to and from the alternative use or uses. The intersection of the supply and demand curves, in each instance, yields the rental price, equaling the discounted marginal value product for the total quantity of the factor available. The price for the general uses, 0C, will be the same as the prices 0E, etc., for any particular use, since the price of the factor must, in equilibrium, be the same in all uses. The general diagram also yields the total quantity that will be sold for rent, 0S1, which will equal the total supply of the land factor available. The sum of the equilibrium quantities (such as EB on the diagram) supplied for particular uses would equal the total supplied for all uses, 0S1.

We have seen that the prices of consumers’ goods are set by consumers’ demand schedules, as determined by their value scales, i.e., by the way that the quantity supplied by producers (the first-rank capitalists) will be valued by consumers. When, in the changing economy, producers have speculative reservation demands, the price will, at any moment, be set by the total demand for the given stock, and this will always tend to approach the true consumers’ demand price. A similar situation obtains in land. The prices of land factors will be determined by the general schedule of the factors’ DMVPs and will be set according to the point of intersection of the total quantity, or stock, of the factor available, with its discounted marginal value productivity schedule. The DMVP, in turn, is, as we have seen at length, determined by the extent to which this factor serves the consumers. The MVP is determined directly by the degree that a factor unit serves the consumers, and the discount is determined by the extent that consumers choose saving-investment as against present consumption. Therefore, the value scales of the consumers determine, given the stocks of original factors, all the various results of the market economy that need to be explained: the prices of the original factors, the allocation of original factors, the incomes to original factors, the rate of time preferences and interest, the length of the production processes in use, and the amounts and types of the final products. In our changing real world, this beautiful and orderly structure of the free market economy tends to be attained through the drive of the entrepreneurs toward making profit and avoiding loss.12

At this point, let us consider a great bugaboo of the Henry Georgists—speculation in land that withholds productive land from use. According to the Georgists, a whole host of economic evils, including the depressions of the business cycle, stem from speculative withholding of ground land from use, causing an artificial scarcity and high rents for the sites in use. We have seen above that speculation in consumers’ goods (and the same will also apply to capital goods) performs the highly useful function of speeding adjustment to the best satisfaction of consumer demand. Yet, curiously, speculation in land is far less likely to occur and is far less important than in the case of any other economic good. For consumers’ or capital goods, being nonpermanent, can be used either now or at some later date. There is a choice between use in the present or use at various times in the future. If the owner of the good estimates that demand for the good will be higher in the future and therefore its price will be greater, he will, provided that the length of waiting time is not too costly in terms of time preference and storage, keep the goods on hand (in inventory) until that date. This serves the consumers by shifting the good from use at present to a more highly valued use in the future.

Land, however, is a permanent resource, as we have seen. It can be used all the time, both in the present and in the future. Therefore, any withholding of land from use by the owner is simply silly; it means merely that he is refusing monetary rents unnecessarily. The fact that a landowner may anticipate that his land value will increase (because of increases in future rents) in a few years furnishes no reason whatever for the owner to refuse to acquire rents in the meanwhile. Therefore, a site will remain unused simply because it would earn zero rent in production. In many cases, however, a land site, once committed to a certain line of production, could not easily or without substantial cost be shifted to another line. Where the landowner anticipates that a better line of use will soon become available or is in doubt on the best commitment for the land, he will withhold the land site from use if his saving in “change-over cost” will be greater than his opportunity cost of waiting and of forgoing presently obtainable rents. The speculative site-owner is, then, performing a great service to consumers and to the market in not committing the land to a poorer productive use. By waiting to place the land in a superior productive use, he is allocating the land to the uses most desired by the consumers.

What probably confuses the Georgists is the fact that many sites lie unused and yet command a capital price on the market. The capital price of the site might even increase while the site continues to remain idle. This does not mean, however, that some sort of villainy is afoot. It simply means that no rents on the site are expected for the first few years, although it will earn positive rents thereafter. The capital value of ground land, as we have seen, sums up the discounted total of all future rents, and these rental sums may exert a tangible influence from a considerable distance in the future, depending on the rate of interest. There is therefore no mystery in the fact of a capital value for an idle site, or in its rise. The site is not being villainously withheld from production.13

Let us now consider the effect of a change in the supply of a land factor. Suppose that there is an increase in the supply of land in general, the supply of labor and savings remaining constant. If the new land is submarginal in relation to land presently in use, it is obvious that the new land will not be used, but will, instead, join its fellow submarginal land sites in idleness. If, on the other hand, the new land is superior, and therefore would earn a positive rent, it comes into use. There has been, however, no increase in labor or capital, so that it will not be profitable for these factors to be employed on a greater total amount of land than before. The new productive land, competing with the older land, will therefore push the previously just-marginal land into the submarginal category. Labor will always employ capital on the best land, and so the new acquisition of supramarginal land will oust the previously marginal land from production. Since the new land is more value-productive than the old marginal land which it replaces, the change increases the total output of goods in the society.

- 12This “rule” by consumers’ valuations holds in so far as entrepreneurs and owners of factors aim at maximum money income. To the extent that they abstain from higher money income to pursue nonmonetary ends (e.g., looking at one’s untilled land or enjoying leisure), the producers’ own valuations will be determining. From the general praxeological point of view, these producers are to that extent acting as consumers. Therefore, the full rule of consumers’ value scales would hold even here. However, for purposes of catallactic market analysis, it may be convenient to separate man as a producer from man as a consumer, even though, considered in his entirety, the same man performs both functions. In that event, we may say that to the extent that nonmonetary goals enter, not consumers’ values are determining, but the values of all individuals in society. For further discussion of this question and of “consumer sovereignty,” see chapter 10 below.

- 13In the free society, as we have indicated above, the site could not originally become the property of anyone until it had been “used” in some way, such as being cleared, cultivated, etc. There need be no subsequent use, however, until rents can be obtained.

D. Supply of Labor

D. Supply of LaborIn the case of a labor factor, the particular demand curve for its use will slope downward, and the particular supply curve of a labor factor for a specific use will slope upward to the right. In fact, since labor is the relatively nonspecific factor, the particular supply curve of a labor factor is likely to be flatter than the supply curve of the (usually more specific) land factor. Thus, the particular supply and demand curves for a labor factor may be as represented in Figure 63.

The general demand curve for a labor factor will also slope downward in the relevant area. One of the complications in the analysis of labor is the alleged occurrence of a “backward supply curve of labor.” This happens when workers react to higher wage rates by reducing their supply of labor hours, thus taking some of their higher incomes as increased leisure. This may very well occur, but it will not be relevant to the determination of the wages of a factor. In the first place, we saw that particular supply curves of a factor will be flat because of the competition of alternative uses. But even the general supply curve of a factor will be “forward-sloping,” i.e., rightward-sloping. For labor, though hardly homogeneous, is a peculiarly nonspecific factor. Therefore, higher wage rates for one set of factors will tend to stimulate other laborers to train themselves or bestir themselves to enter this particular “market.” Since skills differ, this does not mean that all wages will be equalized. It does mean, however, that general supply curves for a labor factor will also be forward-sloping. We might arrange an array of general supply and demand curves for various labor factors as in Figure 64.

The only case in which a backward supply curve may occur is for the total supply of all labor factors, and here the elements are so imprecise, since these factors are not homogeneous, that diagrams are of little avail in analysis. Yet this is an important question. As wage rates in general rise, in all their connexity between various specific labor markets, the supply of all labor (i.e., the quantity of labor-hours) can either increase or decrease, depending on the value scales of the individuals concerned. Rising wages may draw nonworking people into the labor force and induce people to work overtime or to obtain an extra part-time job. On the other hand, it may lead to increased leisure and a falling off in total hours worked. Rising wages may lead to population growth, swelling the total supply of labor “in general,” or may lead to a cutback in population and the taking of some of the gains of increased wages in the form of increased leisure and an increased standard of living per person in the population.14 Changes in the total supply or stock of labor-in-general will affect the particular markets by shifting all the specific schedules to the left if the stock decreases, or to the right if it increases.

A backward supply curve might conceivably take place for a land factor as well, when the owner has a high reserve demand for the land in order to enjoy its unused (in the catallactic sense) beauty. In that case, the land would have an increasing marginal disutility of visual enjoyment forgone, just as leisure is forgone in the process of expending labor. In the case of land, since there is not as great a connexity between land factors as there is between nonspecific labor factors, this circumstance will, in fact, impinge more directly on the market rental price. It may be revealed in a backward general supply curve for the land factor. Higher rental prices offered for his land will then induce the landowner to withhold more of it, taking the higher income partially in nonexchangeable consumption goods as well as in more money received. These cases may be rare in practice, but only because of the freely chosen values of the individuals themselves.

Thus, there is no reason for the would-be preserver of a monument or of a park to complain about the way the market treats his treasured objects. In the free society, these conservationists are at perfect liberty to purchase the sites and preserve them intact. They would, in effect, be deriving consumption services from such acts of preservation.

To return to labor, we have mentioned another component in wage rates. This is the psychic income, or psychic disutility, involved in any particular line of work. People, in other words, are often attracted to a certain line of work or to a specific job by other considerations than the monetary income. There may be positive psychic benefits and satisfactions derived from the particular type of work or from the particular firm employing the worker. Similarly, psychic disutilities may be attached to particular jobs.

These psychic elements will enter into the curves for particular uses. In order to isolate such elements, let us suppose for the moment that all laborers are equally value-productive, that labor is a homogeneous factor. In such a world, all wage rates in all occupations would be equal. All industries need not be equally value-productive for this result to occur. For as a result of the connexity of labor, i.e., its nonspecificity, laborers can enter wide ranges of occupations. If we assume, as we do for the moment, that all laborers are equally value-productive, then they will enter a high-wage industry to push the particular supply curve of labor in that industry downward, while quitting workers raise the supply curve of labor in the low-wage industry.

This conclusion follows from the general tendency toward the uniformity of the price of any good on the market. If all labor were homogeneous and therefore one factor, its price (wage rate) would be uniform throughout industry, just as the pure interest rate tends to be uniform.

Now let us relax one of the conditions of our hypothetical construct.15 While retaining the assumption of equal productivity of all laborers, let us now introduce the possibility of psychic benefits or psychic disutilities accruing to workers at particular jobs. Some jobs are actively liked by most people, others actively disliked. These jobs may be common to certain industries or, more narrowly, to individual firms which may be considered particularly pleasant or unpleasant to work for. What will happen to money wage rates and to the supply of labor in the various occupations? It is obvious that, in the generally disliked occupation or firm, higher money wage rates will be necessary to attract and hold labor in that job. On the other hand, there will be so much labor competing in the generally liked jobs that they will pay lower wage rates. In other words, our amended conclusion is that not money wage rates, but psychic wage rates, will be equalized throughout—psychic wage rates being equal to money wage rates plus or minus a psychic benefit or psychic disutility component.

Many economists have assumed, implicitly or explicitly, an essential homogeneity among laborers. And they have made this assumption not, as we have done, as a purely temporary construct, but as an attempt to describe the real world. The question is an empirical one. It is a fundamental, empirically derived postulate of this book that there is a great variety among men in labor skills, in insight into future events, in ability, intelligence, etc. It seems empirically clear that this is the case.16 The denials seem to be based on the simple faith that all men are “really” equal in all respects or could be made equal under proper conditions. Generally, the assumptions of uniformity and equality are made implicitly rather than explicitly, perhaps because the absurdities and obvious errors of the position would then become clear. For who would deny that not everyone could be an opera singer or a batting champion?

Some writers try to salvage the uniformity assumption by demonstrating that differences in wages occur solely because of the heavy cost of training for certain jobs. Thus, a doctor will earn more than a clerk because, in the nature of the task, a doctor will have to undergo the expenses of years of training (the expenses including actual money costs as well as opportunity costs forgone of earning money in such jobs as clerking). Therefore, in long-run equilibrium, money wage rates will not be uniform in the two fields, but income rates will be enough higher in medicine to just compensate for the loss, so that the net wage or income rates, considered over the person’s lifetime, will be the same.

It is true that costs of training do enter in this way into market wage rates. But they do not account for all wage differentials by any means. Inherent differences in personal ability are also vital. Decades of training will not convert the average person into an opera star or a baseball champion.17

Many writers have based their analyses on the assumption of the homogeneity of all workers. Consequently, when they find that generally well-liked jobs, such as television-directing, pay more than such disliked jobs as ditch-digging, they tend to assume that there is injustice and chicanery afoot. A recognition of differences in labor productivity, however, eliminates this bugbear.18 In such cases, a psychic component still exists that relatively lowers the wage of the better-liked job, but it is offset by the higher marginal value productivity and skill attached to the latter. Since TV-directing takes more skill than ditch-digging, or rather skill that fewer people have, the wage rates in the two occupations cannot be equalized.

- 14There will be such a backward supply curve if the marginal utility of money falls rapidly enough and the marginal disutility of leisure forgone rises rapidly enough as units of labor are sold for higher prices in money.

- 15It will be noted that we have avoided using the very fashionable term “model” to apply to the analyses in this book. The term “model” is an example of an unfortunate bias in favor of the methodology of physics and engineering, as applied to the sciences of human action. The constructs are imaginary because their various elements never coexist in reality; yet they are necessary in order to draw out, by deductive reasoning and ceteris paribus assumptions, the tendencies and causal relations of the real world. The “model” of engineering, on the other hand, is a mechanical construction in miniature, all parts of which can and must coexist in reality. The engineering model portrays in itself all the elements and the relations among them that will coexist in reality. For this distinction between an imaginary construct and a model, the writer is indebted to Professor Ludwig von Mises.

- 16For some philosophical discussions of human variation, see Harper, Liberty, pp. 61–83, 135–41; Roger J. Williams, Free and Unequal (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1953); George Harris, Inequality and Progress (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1898); Herbert Spencer, Social Statics (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1890), pp. 474–82; A.H. Hobbs, The Claims of Sociology (Harrisburg, Pa.: The Stackpole Co., 1951), pp. 23–64; and Hobbs, Social Problems and Scientism (Harrisburg, Pa.: The Stackpole Co., 1953), pp. 254–304.

- 17Cf. Van Sickle and Rogge, Introduction to Economics, pp. 178–81.

- 18For a treatment of wage rates and geography, see the section below on “The Economics of Location and Spatial Relations.”

E. Productivity and Marginal Productivity

E. Productivity and Marginal ProductivityGreat care must be taken in dealing with the productivity concept. In particular, there is danger in using a term such as “productivity of labor.” Suppose, for example, we state that “the productivity of labor has advanced in the last century.” The implication is that the cause of this increase came from within labor itself, i.e., because current labor is more energetic or personally skillful than previous labor. This, however, is not the case. An advancing capital structure increases the marginal productivity of labor, because the labor supply has increased less than the supply of capital goods. This increase in the marginal productivity of labor, however, is not due to some special improvement in the labor energy expended. It is due to the increased supply of capital goods. The causal agents of increased wage rates in an expanding economy, then, are not primarily the workers themselves, but the capitalist-entrepreneurs who have invested in capital goods. The workers are provided with more and better tools, and so their labor becomes relatively scarcer as compared to the other factors.19

That each man receives his marginal value product means that each man is paid what he is worth in producing for consumers. But this does not mean that increases in his worth over the years are necessarily caused by his own improvement. On the contrary, as we have seen, the rise is primarily due to the increasing abundance of capital goods provided by the capitalists.

It is, then, clearly impossible to impute absolute “productivity” to any productive factor or class of factors. In the absolute sense, it is meaningless to try to impute productivity to any factor, since all the factors are necessary to the product. We can discuss productivity only in marginal terms, in terms of the productive contribution of a single unit of a factor, given the existence of other factors. This is precisely what entrepreneurs do on the market, adding and subtracting units of factors in an attempt to achieve the most profitable course of action.

Another illustration of the error in attempting to attribute increased “productivity” to the workers themselves occurs within the various segments of the labor market. As we have seen, there is a definite connexity between all the occupations on the labor market, since labor is the prime nonspecific factor. As a result, while wage rates are not equalized, psychic wage rates will all tend, in the long run, to move together and maintain a given skill-differential between each occupation. Therefore, when a certain branch of industry expands its capital and production, an increase in DMVP, and therefore in wage rates, is not confined to that particular branch. Because of the connexity of the supply of labor, labor tends to leave other industries and enter the new ones, until finally all the wage rates throughout the labor market have risen, while maintaining the same differentials as before.

Suppose, for example, that there is an expansion of capital in the steel industry.20 The MVP of the steel worker increases, and his wage rates go up. The increase in wage rates, however, is governed by the fact that the rise will attract workers from more poorly paid industries. For example, suppose that steel workers are receiving 25 grains of gold per hour, while domestic servants receive 15 grains per hour. Now, under the impetus of expansion, the MVP and hence the wage rate of the steel workers go up to 30 grains. The differential has been increased, inducing domestic servants to enter the steel industry, lowering steel wages, and especially raising servants’ wages, until the differential is re-established. Thus, a rise in capital investment in steel will increase the wages of workers in domestic service. The latter increase is clearly not caused by some sort of increase in the “productivity” or in the quality of the output of the domestic servants. Rather, their marginal value productivity has increased as a result of the greater scarcity of labor in the service trades.

The differentials will not remain precisely constant in practice, of course, since changing investment and changing methods also alter the types of skills required in the economy.

The shift in labor supply will not usually be as abrupt as in our example. Generally, it will take place from one occupation or one grade to a closely similar grade or occupation. Thus, more ditchdiggers might become foremen, more foremen supervisors, etc., so that shifts will take place from grade to grade. It is as if the labor market consisted of linked segments, a change in one segment transmitting itself throughout the chain from each link to the next.

- 19It should be understood throughout that when we refer to increases in wage rates or ground rents in the expanding economy, we are referring to real, and not necessarily to money, wage rates or ground rents.

- 20This assumes, of course, that there is no offsetting decline in capital elsewhere. If there is, then there will be no general rise in wages.

F. A Note on Overt and Total Wage Rates

F. A Note on Overt and Total Wage RatesIt is “total wage rates” that are determined on the market. They tend to be equalized on the market and to be set at the DMVP of the worker. Total wage rates are the money paid out by the employer for labor services. They do not necessarily correspond to the “take-home pay” of the worker. The latter may be called the “overt wage rates.” Thus, suppose that there are two competing employers bidding for the same type of labor. One employer, Mr. A, pays out a certain amount of money, not in direct wages, but in pension funds or other “welfare” benefits. These benefits, it must be realized, will not be added as a gift from the employer to the workers. They will not be additions to the total wage rates. Overt wage rates paid out by Mr. A will instead be correspondingly lower than those paid out by his rival, Mr. B, who does not have to spend on the “welfare” benefits.

To the employer, in other words, it makes no difference in what form workers cost him money, whether in “take-home pay” or in welfare benefits. But he cannot pay more than the worker’s DMVP; i.e., the worker’s total wage income is set by this amount. The worker, in effect, chooses in what form he would like his pay and in what proportion of net wage rates to “welfare” benefits. Part of these benefits is money that the employer might spend to provide particularly pleasant or plush working conditions for all or some of his employees. This cost is part of the total and is deducted from the overt wage rates of the employee.

The institutional manner of paying wage rates is a matter of complete indifference to our analysis. Thus, while “piece rates” or “time rates” may be more convenient in any given industry, they do not differ in essentials; both are wage rates paid for a certain amount of work. With time rates, the employer has in mind a standard of performance which he expects from a worker, and he pays according to that rate.21

- 21For a discussion of these problems, see Mises, Human Action, pp. 598– 600.

G. The "Problem" of Unemployment

G. The “Problem” of UnemploymentAn economic bugbear of our times is “unemployment.” Not only is this considered the pre-eminent problem of the “depression” in the “business cycle”; it is also generally considered the primary “problem” of the “capitalist system,” i.e., of the developed free-market economy. “Well, at least socialism solves the unemployment problem,” is supposed to be the most persuasive argument for socialism.

Of particular interest to us is the sudden emergence of the “unemployment problem” in economic theory. The Keynesians, in the mid-1930’s, inaugurated the fashion of declaiming: Neoclassical economics is all right for its special area, but it assumes “full employment.” Since “orthodox” economics “assumes full employment,” it holds true only so long as “full employment” prevails. If it does not, we enter a Keynesian wonderland where all economic truths are vitiated or reversed.

“Full employment” is supposed to be the condition of no unemployment and therefore the goal at which everyone aims.

In the first place, it should be emphasized that economic theory does not “assume” full employment. Economics, in fact, “assumes” nothing. The whole discussion of alleged “assumptions” reflects the bias of the epistemology of physics, where “assumptions” are made without originally knowing their validity and are eventually tested to see whether or not their consequents are correct. The economist does not “assume”; he knows. He concludes on the basis of logical deduction from self-evident axioms, i.e., axioms that are either logically or empirically incontrovertible.

Now what does economics conclude on the matter of unemployment or “full employment”? In the first place, there is no “problem” involved in the unemployment of either land or capital goods factors. (The latter condition is often known as “idle” or “unused capacity.”) We have seen above that a crucial distinction between land and labor is that labor is relatively scarce. As a result, there will always be land factors remaining unused, or “unemployed.”22 As a further result, labor factors will always be fully employed on the free market to the extent that laborers are so willing. There is no problem of “unemployed land,” since land remains unused for a good reason. Indeed, if this were not so (and it is conceivable that some day it will not be), the situation would be most unpleasant. If there is ever a time when land is scarcer than labor, then land will be fully employed, and some labor factors will either get a zero wage or else a wage below minimum subsistence level. This is the old classical bugbear of population pressing the food supply down to below-subsistence levels, and certainly this is theoretically possible in the future.

This is the only case in which an “unemployment problem” might be said to apply in the free market. But even here, if we consider the problem carefully, we see that there is no unemployment problem per se. For if what a man wants is simply a “job,” he could work for zero wages, or even pay his “employer” to work for him. In other words, he could earn a “negative wage.” Now this could never happen, for the good reason that labor is a disutility, especially as compared to leisure or “play.” Yet all the worry about “full employment” makes it appear that the “job,” and not the income from the job, is the great desideratum. If that were really the case, then there would be negative wages, and there would be no unemployment problem either. The fact that no one will work for zero or negative wages implies that in addition to whatever enjoyment he receives, the laborer requires a monetary income from his work. So what the worker wants is not just “employment” (which he could always get in the last resort by paying for it) but employment at a wage.

But once this is recognized, the whole modern and Keynesian emphasis on employment has to be revalued. For the great missing link in their discussion of unemployment is precisely the wage rate. To talk of unemployment or employment without reference to a wage rate is as meaningless as talking of “supply” or “demand” without reference to a price. And it is precisely analogous. The demand for a commodity makes sense only with reference to a certain price. In a market for goods, it is obvious that whatever stock is offered as supply, it will be “cleared,” i.e., sold, at a price determined by the demand of the consumers. No good need remain unsold if the seller wants to sell it; all he need do is lower the price sufficiently, in extreme cases even below zero if there is no demand for the good and he wants to get it off his hands. The situation is precisely the same here. Here we are dealing with labor services. Whatever supply of labor service is brought to market can be sold, but only if wages are set at whatever rate will clear the market.

We conclude that there can never be, on the free market, an unemployment problem. If a man wishes to be employed, he will be, provided the wage rate is adjusted according to his DMVP. But since no one wants to be simply “employed” without getting what he considers sufficient payment, we conclude that employment per se is not even a desired goal of human action, let alone a “problem.”

The problem, then, is not employment, but employment at an above-subsistence wage. There is no guarantee that this situation will always obtain on the free market. The case mentioned above—scarcity of land in relation to labor—can lead to a situation where a worker’s DMVP is below a subsistence wage for him. There also may be so little capital invested per worker that any wage will be below-subsistence for many people. Even in a relatively prosperous society there may be individual workers so infirm or lacking in skill that their particular talents could not command an above-subsistence wage. In that case, they could survive only through the gifts of those who are making above-subsistence wages.

But what of the able-bodied worker who “can’t find a job”? This situation cannot obtain. In those cases, of course, where a worker insists on a certain type of job or a certain minimum wage rate, he may well remain “unemployed.” But he does so only of his own volition and on his own responsibility. Thus, suppose that perhaps half the labor force suddenly insisted that they would not work unless they received a job in New York City in the television industry. Obviously, “unemployment” would suddenly become enormous. This is only a large-scale example of something that is always going on. There may be a shift of industry away from one town or region and toward another. A worker may decide that he wants to remain in the old town and insists on looking for a job there. If he fails to get one, however, the fault lies with himself and not with the “capitalist system.” The same is true of a clerk who insists on working only in the TV industry, or of a radio employee who refuses to leave for television and insists on working only in radio. We are not condemning these workers here. We are simply saying that by their decisions they are themselves choosing not to be employed.

The able-bodied in a developed economy can always find work, and work that will pay an over-subsistence wage. This is so because labor is scarcer than land, and enough capital has been invested to raise the marginal value product of laborers sufficiently to pay such a wage. But while this is true in the general labor market, it is not necessarily true for particular labor markets, for particular regions or occupations, as we have just seen.

If a worker can withdraw from the labor market by insisting on a certain type of work or location of work, he can also withdraw by insisting on a certain minimum wage payment. Suppose a man insisted that he would not work at any job unless he is paid 500 gold ounces per year. If his best available DMVP is only 100 gold ounces per year, he will remain unemployed. Whenever a man insists on a wage higher than his DMVP, he will remain unemployed, i.e., unemployed at the wage that he insists upon. But then this unemployment is not a “problem,” but a voluntary choice on the part of the idle person.23

The “full employment” provided by the free market is employment to the extent that workers wish to be employed. If they refuse to be employed except at places, in occupations, or at wage rates they would like to receive, then they are likely to be choosing unemployment for substantial periods.24

It might be objected that workers often do not know what job opportunities await them. This, however, applies to the owner of any goods up for sale. The very function of marketing is the acquisition and dissemination of information about the goods or services available for sale. Except to those writers who posit a fantastic world where everyone has “perfect knowledge” of all relevant data, the marketing function is a vital aspect of the production structure. The marketing function can be performed in the labor market, as well as in any other, through agencies or other means for the discovery of who or where the potential buyers and sellers of a particular service may be. In the labor market this has been done through “want ads” in the newspapers, employment agencies used by both employer and employee, etc.

Of course “full employment,” as an absolute ideal, is absurd in a world where leisure is a positive good. A man may choose idleness in order to obtain leisure; he benefits (or believes he benefits) more from this than from working at a job.25 We can see this truth more clearly if we consider the hours of the work week. Will anyone maintain that an 80-hour work week is necessarily better than a 40-hour week? Yet the former clearly represents a fuller employment of labor than the latter.

One alleged example of a possible case of involuntary unemployment on the free market has been suggested by Professor Hayek.26 Hayek maintains that when there is a shift from investment to consumption, and therefore a shortening of the production structure on the market, there will be a necessary temporary unemployment of workmen thrown out of work in the higher stages, lasting until they can be reabsorbed in the shorter processes of the later stages. It is true that there is a loss in income, as well as a loss in capital, from a shift to shorter processes. It is also true that the shortening of the structure means that there is a transition period when, at final wage rates, there will be unemployment of the men displaced from the longer processes. However, during this transition period there is no reason why these workers cannot bid down wage rates until they are low enough to enable the employment of all the workers during the transition. This transition wage rate will be lower than the new equilibrium wage rate. But at no time is there a necessity for unemployment.

The ever-recurring doctrine of “technological unemployment”—man displaced by the machine—is hardly worthy of extended analysis. Its absurdity is evident when we look at the advanced economy and compare it with the primitive one. In the former there is an abundance of machines and processes completely unknown to the latter; yet in the former, standards of living are far higher for far greater numbers of people. How many workers have been “displaced” because of the invention of the shovel? The technological unemployment motif is encouraged by the use of the term “labor-saving devices” for capital goods, which to some minds conjure up visions of laborers being simply discarded. Labor needs to be “saved” because it is the pre-eminently scarce good and because man’s wants for exchangeable goods are far from satisfied. Furthermore, these wants would not be satisfied at all if the capital-goods structure were not maintained. The more labor is “saved,” the better, for then labor is using more and better capital goods to satisfy more of its wants in a shorter amount of time.

Of course, there will be “unemployment” if, as we have stated, workers insist on their own terms for work, and these terms cannot be met. This applies to technological changes as well as any other. The clerk who, for some reason, insists nowadays on working only for a blacksmith or in an old-fashioned general store may well have chosen a large dose of idleness. Any workers who insisted on working in the buggy industry or nothing found themselves, no doubt, unemployed after the development of the automobile.

A technological improvement in an industry will tend to increase employment in that industry if the demand for the product is elastic downward, so that the greater supply of goods induces greater consumer spending. On the other hand, an innovation in an industry with inelastic demand downward will cause consumers to spend less on the more abundant products, contracting employment in that industry. In short, the process of technological innovation shifts workers from the inelastic-demand to the elastic-demand industries. One of the major sources of new employment demand is in the industry making the new machines.27

- 22Capital goods will remain unemployed because of previous entrepreneurial error, i.e., investing in the wrong type of capital goods.

- 23See Mises, Human Action, pp. 595–98. As Mises concludes, “Unemployment in the unhampered market is always voluntary.” Particularly recommended is Mises’ critique of the theory of “frictional unemployment.”

- 24Economics does not “assume mobility of labor.” It simply analyzes the consequences of a laborer’s decision to be “mobile” or “immobile,” the latter amounting to a voluntary choice of at least temporary unemployment.

- 25The “idleness” referred to here is catallactic, and not necessarily total. In other words, it means that a man does not seek to sell his labor services for money and therefore does not enter the societal labor market. He might well be very “busy” working at hobbies, etc.

- 26Hayek, Prices and Production, pp. 91–93.

- 27Cf. Fred R. Fairchild and Thomas J. Shelly, Understanding Our Free Economy (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1952), pp. 478–81.

3. Entrepreneurship and Income

3. Entrepreneurship and IncomeA. Costs to the Firm

A. Costs to the FirmWe have seen the basis on which the prices of the factors of production and the interest rate are determined. Looked at from the point of view of an individual entrepreneur, payments to factors are money costs. It is clear that we cannot simply rest on the old classical law that prices of products tend, in the long run, to be equal to their costs of production. Costs are not fixed by some Invisible Hand, but are determined precisely by the total force of entrepreneurial demand for factors of production. Basically, as Böhm-Bawerk and the Austrians pointed out, costs conform to prices, and not vice versa. Confusion may arise because, looked at from the point of view of the individual firm rather than of the economist, it appears as if costs (at least in the sense of the prices of factors) are somehow given, and beyond one’s control.28 If a firm can command a selling price that will more than cover its costs, it remains in business; if not, it will have to leave. The illusion of externally determined costs is prevalent because, as we shall presently see, most factors can be employed in a wide variety of firms, if not industries. If we take the broader view of the economist, however, the various “costs,” i.e., prices of factors, determined by their various DMVPs in alternative uses, are ultimately determined solely by consumers’ demand for all uses. It must not be forgotten, furthermore, that changes in demand and selling price will change the prices and incomes of specialized factors in the same direction. The “cost curves” so fashionable in current economics assume fixed factor prices, thereby ignoring their variability, even for the single firm.

It might be noted that, in this work, there is none of that plethora and tangle of “cost curves” which fill the horizon of almost every recent “neoclassical” work in economics.29 This omission has been deliberate, since it is our contention that the cost curves are at best redundant (thus violating the simplicity principle of Occam’s Razor), and at worst misleading and erroneous.

As an explanation of the pricing of factors and the allocation of output it is obvious that cost curves add nothing new to discussion in terms of marginal productivity. At best, the two are reversible. This can be clearly seen in such texts as E.T. Weiler’s The Economic System and George J. Stigler’s Theory of Price.30 But, in addition, the shift brings with it many grave deficiencies and errors. This is revealed in the very passage in which Stigler explains the reasons for his switch from a perfunctory discussion of productivity to a lengthy treatment of cost curves:

The law of variable proportions has now been explored sufficiently to permit a transition to the cost curves of the individual firm. The fundamentally new element in the discussion will, of course, be the introduction of prices of the productive services. The transition is made here only for the case of competition—that is, the prices of the productive services are constant because the firm does not buy enough of any service to affect its price.31

But by introducing given prices of productive services, the contemporary theorist really abandons any attempt to explain these prices. This is one of the cardinal errors of the currently fashionable theory of the firm. It is highly superficial. One of the aspects of this superficiality is the assumption that prices of productive services are given, without any attempt to explain them. To furnish an explanation, marginal productivity analysis is necessary.

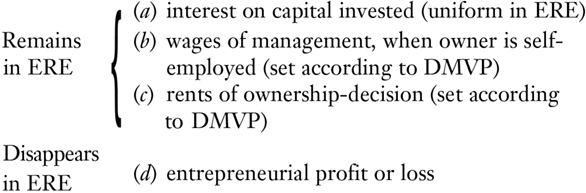

Marginal productivity analysis and the profit motive are sufficient to explain the prices of productive factors and their allocation to various firms and industries in the economy. Furthermore, there are in production theory two important and interesting concepts involving periods of time. One is what we may call the “immediate run”—the market prices of commodities and factors on the basis of given stocks and speculative demands and given consumer valuations. The immediate run is important, since it provides an explanation of the actual market prices of all goods at any time. The other important concept is that of the “final price,” or the long-run equilibrium price, i.e., the price that would be established in the ERE. This is important because it reveals the direction in which the immediate-run market prices tend to move. It also permits the analytic isolation of interest, as compared to profit and loss, in entrepreneurial incomes. In the ERE all factors will receive their discounted marginal value product, and interest will be pure time preference; there will be no profit and loss.

The interesting phases, then, are the immediate run and the long run. Yet cost-curve analysis deals almost exclusively with a hybrid intermediate phase known as the “short run.” In this short run, “costs” are sharply divided into two categories: fixed (which must be incurred regardless of the amount produced) and variable (which vary with output). This whole construction is a highly artificial one. There is no actual “fixity” of costs. Any alleged fixity depends purely on the length of time involved. In fact, suppose that production is zero. The “cost-curve theorists” would have us believe that even at zero output there are fixed costs that must be incurred: rent of land, payment of management, etc. However, it is clear that if data are frozen—as they should be in such an analysis—and the entrepreneurs expect a situation of zero output to continue indefinitely, these “fixed” costs would become “variable” and disappear very quickly. The rent contract for land would be terminated, and management fired, as the firm closed its doors.

There are no “fixed” costs; rather there are different degrees of variability for different productive factors. Some factors are best used in a certain quantity over a certain range of output, while others yield best results over other ranges of output. The result is not a dichotomy into “fixed” and “variable” costs, but a condition of many degrees of variability for the various factors.32

Even if none of these difficulties existed, it is hard to see why the “short run” should be picked out for detailed analysis, when it is merely one way station, or rather a series of way stations, between the important periods of time: the immediate run and the long run. Analytically, the cost-curve approach is at best of little interest.33

With these caveats, let us now turn to an analysis of the costs of the firm. Let us consider what will happen to costs at alternate hypothetical levels of output. There are two elements that determine the behavior of average costs, i.e., total costs per unit output.

(a) There are “physical costs”—the amounts of factors that must be purchased in order to obtain a certain physical quantity of output. These are the obverse of “physical productivity”— the amounts of the physical product that can be produced with various amounts of factors. This is a technological problem. Here the question is not marginal productivity, where one factor is varied while others remain constant in quantity. Here we concentrate on the scale of output when all factors are permitted to vary. Where all factors and the product are completely divisible, a proportionate increase in the quantities of all the factors must lead to an equally proportionate increase in physical output.34 This may be called the law of “constant returns to scale.”

(b) The second determinant of average costs is factor prices. “Pure competition” theorists assume that these prices remain unchanged with a changing scale of output, but this is impossible.35 As any firm’s scale of output increases, it necessarily bids factors of production away from other firms, raising their prices in the process. And this is particularly true for labor and land factors, which cannot be increased in supply via new production. The increase in factor prices as output increases, combined with constant physical costs, raises the average money cost per unit output. We may therefore conclude that if factors and product were perfectly divisible, average cost would always be increasing.

In the productive world, perfect divisibility does not always, or even usually, obtain. Units of factors and of output are indivisible, i.e., they are not purely divisible into very small units. First, the product may be indivisible. Thus, suppose that three units of factor A + 2 units of factor B may combine to produce one refrigerator. Now it may be true that 6A + 4B will produce two refrigerators, according to our law of returns to scale. But it is also true that 4A + 3B will not produce one-and-a-fraction refrigerators. There are bound to be gaps where an increased supply of factors will not lead to an increased product, because of the technological indivisibility of the unit product.

In the areas of the gaps, average costs increase rapidly, since new factors are being hired with no product forthcoming; then, when expenditures on factors are increased sufficiently to produce more of the product, there is a precipitate decline in average cost compared to the situation during the gap. As a result, no businessman will knowingly invest in the area of the gaps. To invest more without yielding a product is sheer waste, and so businessmen will invest only in the trough points outside the gap areas.36

Secondly, and more important, the productive factors may be indivisible. Because of this indivisibility, it is not possible simply to double or halve the quantities of input of every one of the productive services simultaneously. Each factor has its own technological unit size. As a result, almost all business decisions take place in zones in which many factors have to remain constant while others (the more divisible ones) may vary. And these relative divisibilities and indivisibilities are due, not to variations in periods of time, but to the technological size of the various units. In any productive operation there will be many varieties of indivisibility.

Professor Stigler presents the example of a railroad track, a factor capable of handling up to 200 trains a day.37 The track is most efficiently utilized when train runs total precisely 200 a day. This is the technologically “ideal” output and may be the one for which the track was designed. Now what happens when output is below 200? Suppose output is only 100 per day. The divisible factors of production will then be cut in half by the owners of the railroad. Thus, if engineers are divisible, the railroad will hire half as many engineers or hire its engineers for half their usual number of hours. But (and this is the critical point here) the railroad cannot cut the track in half and operate on half a track. The technological unit of “track” being what it is, the number of tracks has to remain at one. Conversely, when output increases to 200 again, other productive services may be doubled, but the quantity of track remains the same.38

What happens should output increase to 250 trains a day—a 25-percent increase over the planned quantity? Divisible services such as engineers may be increased by one-fourth; but the track must either remain at one—and be overutilized—or be increased to two. If it is increased, the tracks will again be underutilized at 250, because the “ideal” output from the point of view of utilizing the tracks is now 400.

When an important indivisible factor is becoming less and less underutilized, the tendency will be for “increasing returns,” for decreasing average costs as output increases. When an important indivisible factor is becoming more and more overutilized, there is a tendency for increasing average costs.

In some spheres of production, indivisibilities may be such that full utilization of one indivisible factor requires full utilization of all.39 In that case, all the indivisible factors move together and can be lumped together for our purposes; they become the equivalent of one indivisible factor, such as the railroad track. In such cases again, average costs will first decline with an increase in output, as the increased output remedies an underutilization of the lumped indivisible factors. After the technologically most efficient point is reached, however, costs will increase, given the indivisible factors. The tendency for costs to decline will, in addition, be offset by the rise in factor prices caused by the increase in output.

In the overwhelming majority of cases, however, each factor will differ from the others in size and degree of divisibility. As a consequence, any size or combination chosen might utilize one indivisible factor most efficiently, but at the expense of not utilizing some other indivisible factor at peak efficiency. Suppose we consider a hypothetical schedule of average money cost at each alternative output. When we start at a very low level of output, all the indivisible factors will be underutilized. Then, as we expand production, average costs will decrease unless offset by the price rise for those divisible factors needed to expand production. As soon as one of the indivisible factors is fully utilized and becomes overworked, average costs will rise sharply. Later, a tendency toward decreasing costs sets in again as another underutilized factor becomes more fully utilized. The result is an alternating series of decreases and increases in average costs as output increases. Eventually, a point will be reached at which more indivisible factors will be overutilized than underutilized, and from then on the general trend of average cost as output increases will be upward. Before that point, the trend will be downward.

Mingling with these influences from the technological side of costs are the continuing rises in factor prices, which also become more important as output increases.

In sum, as Mises states:

Other things being equal, the more the production of a certain article increases, the more factors of production must be withdrawn from other employments in which they would have been used for the production of other articles. Hence—other things being equal—average production costs increase with the increase in the quantity produced. But this general law is by sections superseded by the phenomenon that not all factors of production are perfectly divisible and that, as far as they can be divided, they are not divisible in such a way that full utilization of one of them results in full utilization of the other imperfectly divisible factors.40

Some indivisible factors, such as the railroad track, can be available in only one particular size. Other indivisible factors, such as machinery, can be built in various sizes. Cannot a small factory, then, use small-scale machinery which will be just as efficient as large-scale machinery in a larger factory, and would this not eliminate indivisibilities and result in constant costs? No, for here too, one particular size will probably be most efficient. Below the most efficient size, operating the machine will be more costly. Thus, as Stigler says, “fitting together of the parts of a ten-horsepower motor does not require ten times the labor necessary to fit those of a one-horsepower motor. Similarly, a truck requires one driver, whether it has a half-ton or two-ton capacity.”41

It is also true that an oversized machine will be more costly than the optimum. But this will be no limitation on the size of the firm, for a large firm can simply use several (smaller) optimum-sized machines instead of one huge machine.

Labor is usually treated as a perfectly divisible factor, as one that varies directly with the size of the output. But this is not true. As we have seen, the truck driver is not divisible into fractions. Further, management tends to be an indivisible production factor. So also salesmen, advertising, cost of borrowing, research expenditures, and even insurance for actuarial risk. There are certain basic costs in borrowing which simply arise from investigating, paperwork, etc. These will tend to be proportionately smaller the larger the size—another indivisibility, with returns increasing over a certain area. Also, the broader the coverage, the lower insurance premiums will be.42

Then there are the well-known gains from the increase in the division of labor with larger outputs. The benefits from the division of labor may be considered indivisible. They arise from the specialized machines that must first be used with a larger product, and similarly from the increased labor skills of specialists. Here too, however, there is a point beyond which no further specialization is possible or where specialization is subject to increasing costs. Management has usually been stressed as particularly subject to overutilization. Even more important is the factor of ultimate-decision-making ability, which cannot be enlarged to the extent that management can.

What any given firm’s size and output will be is therefore subject to a host of conflicting determinants, some impelling a limitation, some an expansion, of size. At what point any firm will settle depends on the concrete data of the actual case and cannot be decided by economic analysis. Only the actual entrepreneur, through the give and take of the market, can decide where the maximum-profit size is and can set the firm at that point. This is the task of the businessman and not of the economist.43

Furthermore, the cost-curve diagrams, so simple and smooth in the textbooks, misinterpret real conditions. We have seen that there are a whole host of determinants which tend at any point toward increasing and toward decreasing costs. It is, of course, true that an entrepreneur will seek to produce at the point of maximum profit, i.e., of maximum net returns over costs. But the factors that influence his decision are too numerous and their interactions too complex to be captured in cost-curve diagrams.